细菌性阴道病(BV)是由细菌过度生长引起的阴道疾病。[6] [9]常见症状包括阴道分泌物增多,通常闻起来像鱼。[2]分泌物通常为白色或灰色。[2]可能会发生排尿灼热。[2]瘙痒是不常见的。[2] [6]偶尔也可能没有症状。[2] BV大约使其他一些性传播感染(包括艾滋病毒/艾滋病)感染的风险增加一倍。[8] [10]它还增加了孕妇早期分娩的风险。[3] [11]

BV是由阴道中天然存在的细菌的不平衡引起的。[4] [5]最常见的细菌类型发生变化,细菌总数增加了一百到一千倍。[6]通常,乳酸杆菌以外的细菌变得更常见。[12]风险因素包括冲洗,新的或多个性伴侣,抗生素和使用宫内节育器等。[5]但是,它不被视为性传播感染。[13]怀疑根据症状进行诊断,并且可以通过测试阴道分泌物并发现阴道pH值高于正常值以及大量细菌来验证[6]。 BV经常与阴道酵母菌感染或毛滴虫感染相混淆。[7]

通常用抗生素治疗,如克林霉素或甲硝唑。[6]这些药物也可用于妊娠的第二或第三个三个月。[6]然而,这种情况经常在治疗后再次出现。[6]益生菌可能有助于防止再次发生。[6]目前尚不清楚益生菌或抗生素的使用是否会影响妊娠结局。[6] [14]

BV是育龄妇女最常见的阴道感染。[5]在任何特定时间受影响的女性比例在5%到70%之间。[8] BV在非洲部分地区最常见,在亚洲和欧洲最不常见。[8]在美国,大约30%的14至49岁女性受到影响。[15]一个国家的族裔群体之间的差异很大。[8]虽然已经记录了大部分记录病史中的BV样症状,但第一个明确记录的病例发生在1894年。[1]

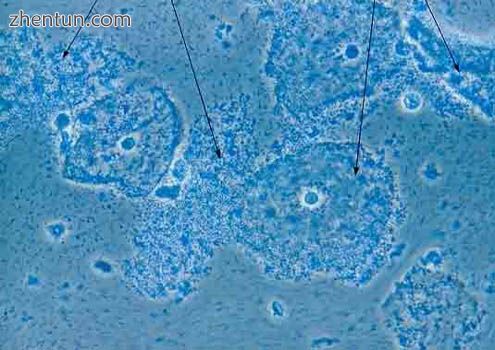

细菌性阴道病的显微照片 - 子宫颈细胞覆盖有杆状细菌,阴道加德纳菌(箭头)。

目录

1 症状和体征

1.1 并发症

2 原因

3 诊断

3.1 Amsel标准

3.2 染色

3.3 纽金特得分

4 防治

5 治疗

5.1 抗生素

5.2 益生菌

6 流行病学

7 参考

体征和症状

常见症状包括阴道分泌物增多,通常闻起来像鱼。 分泌物通常为白色或灰色。 排尿可能会有烧灼感。 偶尔也可能没有症状。[2]

排出物涂在阴道壁上,并且通常没有明显的刺激,疼痛或红斑(发红),尽管有时会发生轻微的瘙痒。相比之下,正常的阴道分泌物在整个月经周期中的稠度和量会有所不同,并且在排卵期间最明显 - 在该期间开始前约两周。一些从业者声称BV在几乎一半受影响的女性中无症状,[16]尽管其他人认为这通常是一种误诊。[17]

并发症

虽然以前被认为仅仅是一种滋扰性感染,但未经治疗的细菌性阴道病可能会导致对包括艾滋病毒在内的性传播感染和妊娠并发症的易感性增加[18] [19]。

已经表明,患有细菌性阴道病(BV)的HIV感染女性比没有BV的女性更容易将HIV传播给性伴侣。[10] BV的诊断标准也与诱导HIV表达的女性生殖道因子有关。[18]

有证据表明BV与艾滋病毒/艾滋病等性传播感染率上升有关。[18] BV与HIV脱落增加高达六倍有关。 BV是病毒脱落和单纯疱疹病毒2型感染的危险因素。 BV可能会增加感染或重新激活人乳头瘤病毒(HPV)的风险。[18] [20]

此外,细菌性阴道病是一种并发妊娠的并发症,可能会增加妊娠并发症的风险,最明显的是早产或流产。[21] [22]患有BV的孕妇患绒毛膜羊膜炎,流产,早产,胎膜早破和产后子宫内膜炎的风险较高。[23]接受体外受精治疗的BV女性植入率较低,早期妊娠丢失率较高[18] [20]。

原因

主要文章:细菌性阴道病菌微生物群列表

健康的阴道微生物群由既不会引起症状或感染的物种组成,也不会对怀孕产生负面影响。它主要由乳杆菌属物种控制。[12] [24] BV的定义是阴道微生物群的不平衡,乳酸杆菌数量下降。虽然感染涉及许多细菌,但据信大多数感染始于阴道加德纳菌,从而产生生物膜,这使得其他机会性细菌能够繁殖。[9] [25]

开发BV的主要风险之一是冲洗,这会改变阴道微生物群并使女性易患BV。[26]由于这个原因和其他原因,美国卫生和公共服务部以及各医疗机构强烈反对打瞌睡。[26]

BV是盆腔炎,HIV,性传播感染(STI),生殖和产科疾病或阴性结果的危险因素。性行为不治的人有可能患上细菌性阴道病。[9]

细菌性阴道病有时可能会影响绝经后的女性。此外,亚临床缺铁可能与妊娠早期的细菌性阴道病有关。[27] 2006年2月在美国妇产科杂志上发表的一项纵向研究表明,即使考虑到其他风险因素,社会心理压力和细菌性阴道病仍然存在联系。[28]暴露于杀精子剂壬苯醇醚-9不会影响发生细菌性阴道病的风险。[29]

拥有女性伴侣会使BV的风险增加60%。 与BV相关的细菌已从雄性生殖器中分离出来。 在受感染的雌性的雄性伴侣中,在阴茎,冠状沟和男性尿道中发现了BV微生物群。 没有接受过包皮环切术的伴侣可能会成为一个“水库”,增加性生活后感染的可能性。 BV相关微生物群的另一种传播方式是通过皮肤 - 皮肤转移给女性性伴侣。 BV可通过来自女性和男性生殖器的微生物群的会阴肠细菌传播。[18]

诊断

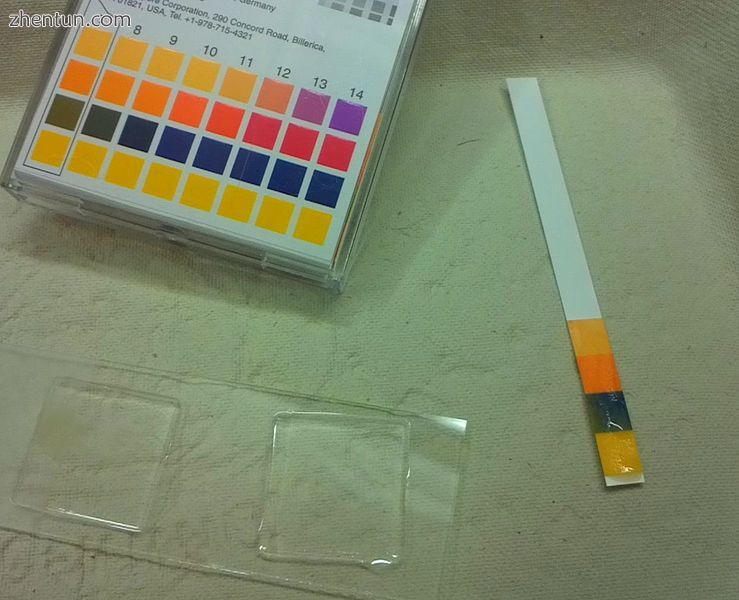

用于检测阴道碱化的pH指示剂(此处显示约pH 8),以及显微镜载玻片以显微镜检测线索细胞。

为了诊断细菌性阴道病,应该从阴道内部取出拭子。这些拭子应进行以下测试:

湿装上具有特色的“鱼腥味”。该测试称为气味测试,通过向含有阴道分泌物的显微镜载玻片中加入少量氢氧化钾来进行。一种特征性的鱼腥味被认为是一种积极的气味测试,并提示细菌性阴道病。

酸度减少。为了控制细菌生长,阴道通常是微酸性的,pH值为3.8-4.2。将排出物的拭子放在石蕊试纸上以检查其酸度。 pH大于4.5被认为是碱性的并且提示细菌性阴道病。

潮湿的坐骑上存在线索细胞。与气味试验类似,通过将一滴氯化钠溶液置于含有阴道分泌物的载玻片上进行线索细胞试验。如果存在,可以在显微镜下观察线索细胞。它们之所以如此命名,是因为它们提供了分泌物背后原因的线索。这些是涂有细菌的上皮细胞。

除了放电本身之外,两个阳性结果足以诊断BV。如果没有出院,则需要所有三个标准。[30] [需要非主要来源]细菌性阴道病的鉴别诊断包括以下内容:[31]

正常的阴道分泌物。

念珠菌病(鹅口疮或酵母菌感染)。

滴虫病,由阴道毛滴虫引起的感染。

需氧性阴道炎[32]

疾病控制中心(CDC)将性传播感染定义为“可通过性活动获得和传播的病原体引起的各种临床综合症和感染。”[33]但疾病预防控制中心并未将BV特异性地识别为性传播感染。 13]

Amsel标准

在临床实践中,可以使用Amsel标准诊断BV:[30]

薄,白色,黄色,均匀放电

显微镜下的线索细胞

阴道液的pH值> 4.5

加入碱 - 10%氢氧化钾(KOH)溶液时释放出腥味。

至少应有四个标准中的三个用于确诊。[34]对Amsel标准的修改接受存在两个而不是三个因素,并且被认为是同样的诊断。

革兰染色

另一种方法是使用Gram染色的阴道涂片,使用Hay / Ison [35]标准或Nugent [23]标准。 Hay / Ison标准定义如下:[34]

1级(正常):乳杆菌形态型占优势。

2级(中级):存在一些乳酸杆菌,但也存在Gardnerella或Mobiluncus形态类型。

3级(细菌性阴道病):主要是Gardnerella和/或Mobiluncus形态类型。乳酸杆菌很少或没有。 (Hay et al。,1994)

Gardnerella vaginalis是BV的主要罪魁祸首。 Gardnerella vaginalis是一种短杆(coccobacillus)。因此,线索细胞和革兰氏可变球杆菌的存在是细菌性阴道病的指示或诊断。

纽金特得分

Nugent评分现在很少被医生用,因为阅读幻灯片需要时间,需要使用经过培训的显微镜专家。[4]通过组合三个其他分数生成0-10的分数。分数如下:

0-3被认为是BV的负数

4-6被认为是中间的

7+被认为是BV的指示。

计算至少10-20个高功率(1000×油浸)场并确定平均值。

乳酸杆菌形态类型 - 每个高功率(1000×油浸)场的平均值。查看多个字段。

Gardnerella / Bacteroides形态类型 - 平均每高功率(1000×油浸)场。查看多个字段。

弯曲的可变杆 - 平均每高功率(1000×油浸)场。查看多个字段(请注意,此因素不太重要 - 只有0-2的分数可能)

得分0> 30

得分为15-30

得分2为14

得分3 <1(这是一个平均值,因此结果可以> 0,但<1)

得分4为0

得分0为0

得分1为<1(这是一个平均值,因此结果可以> 0,但<1)

得分2为1-4

得分3为5-30

得分4> 30

得分0为0

得分1 <5

得分2为5+

使用Nugent标准将使用Affirm VPIII的DNA杂交测试与革兰氏染色进行比较。[36] Affirm VPIII测试可用于对有症状的女性进行BV的快速诊断,但使用昂贵的专有设备来读取结果,并且不检测导致BV的其他病原体,包括Prevotella spp,Bacteroides spp和Mobiluncus spp。

预防

建议降低风险的一些措施包括:不要冲洗,避免性行为,或限制性伴侣的数量。[37]

一项综述得出结论,益生菌可能有助于防止再次发生。[6]另一项审查发现,虽然有暂定证据,但并不足以推荐将其用于此目的。[38]

早期证据表明,男性伴侣的抗生素治疗可以重建男性泌尿生殖道的正常微生物群,并防止感染复发。[18]然而,2016年Cochrane评价发现高质量证据表明,治疗患有细菌性阴道病的女性的性伴侣对受影响女性的症状,临床结果或复发没有影响。它还发现,这种治疗可能会导致受治疗的性伴侣报告增加的不良事件。[18]

治疗

抗生素

治疗通常使用抗生素甲硝唑或克林霉素。[39]它们可以口服或阴道内使用。[39]然而,大约10%至15%的人没有使用第一疗程的抗生素改善,并且已记录了高达80%的复发率。[20]尽管含雌激素的避孕药可减少复发,但同一治疗前或治疗后伴侣的性活动复发率增加,避孕套使用不一致[40]。当克林霉素给予妊娠22周前有症状的孕妇时,妊娠37周前早产的风险较低。[41]

其他可能起作用的抗生素包括大环内酯类,林可酰胺类,硝基咪唑类和青霉素类。[18]

细菌性阴道病不被视为性传播感染,不建议对患有细菌性阴道病的女性的男性性伴侣进行治疗。[42] [43]

益生菌

2009年Cochrane评价发现暂时但缺乏证据证明益生菌可作为治疗BV。[44] 2014年的审查得出了同样的结论。[45] 2013年的一项审查发现了一些支持在怀孕期间使用益生菌的证据。[46] BV的首选益生菌是在阴道内给予高剂量乳酸杆菌(约109 CFU)的益生菌。[47] 阴道给药优于口服给药。[47] 长期重复疗程似乎比短期疗程更有希望。[47]

流行病学

BV是育龄妇女最常见的阴道感染。[5] 在任何特定时间受影响的女性比例在5%到70%之间。[8] BV在非洲部分地区最常见,在亚洲和欧洲最不常见。[8] 在美国,年龄在14至49岁之间的人中约有30%受到影响。[15] 一个国家的族裔群体之间的差异很大。[8]

参考

Borchardt, Kenneth A. (1997). Sexually transmitted diseases : epidemiology, pathology, diagnosis, and treatment. Boca Raton [u.a.]: CRC Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780849394768. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

"What are the symptoms of bacterial vaginosis?". 21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

Queena JT, Spong CY, Lockwood CJ, eds. (2012). Queenan's management of high-risk pregnancy : an evidence-based approach (6th ed.). Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 262. ISBN 9780470655764.

Bennett, John (2015). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 9781455748013.

"Bacterial Vaginosis (BV): Condition Information". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

Donders, GG; Zodzika, J; Rezeberga, D (April 2014). "Treatment of bacterial vaginosis: what we have and what we miss". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 15 (5): 645–57. doi:10.1517/14656566.2014.881800. PMID 24579850.

Mashburn, J (2006). "Etiology, diagnosis, and management of vaginitis". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 51 (6): 423–30. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2006.07.005. PMID 17081932.

Kenyon, C; Colebunders, R; Crucitti, T (December 2013). "The global epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 209 (6): 505–23. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.006. PMID 23659989.

Clark, Natalie; Tal, Reshef; Sharma, Harsha; Segars, James (2014). "Microbiota and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 32 (1): 043–049. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1361822. ISSN 1526-8004. PMC 4148456. PMID 24390920.

Bradshaw, CS; Brotman, RM (July 2015). "Making inroads into improving treatment of bacterial vaginosis - striving for long-term cure". BMC Infectious Diseases. 15: 292. doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1027-4. PMC 4518586. PMID 26219949.

"What are the treatments for bacterial vaginosis (BV)?". National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 15 July 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

Nardis, C.; Mastromarino, P.; Mosca, L. (September–October 2013). "Vaginal microbiota and viral sexually transmitted diseases". Annali di Igiene. 25 (5): 443–56. doi:10.7416/ai.2013.1946. PMID 24048183.

"Bacterial Vaginosis – CDC Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

Othman, M; Neilson, JP; Alfirevic, Z (24 January 2007). "Probiotics for preventing preterm labour". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005941. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005941.pub2. PMID 17253567.

"Bacterial Vaginosis (BV) Statistics Prevalence". cdc.gov. 14 September 2010. Archived from the original on 22 February 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

Schwebke JR (2000). "Asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis: response to therapy". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 183 (6): 1434–9. doi:10.1067/mob.2000.107735. PMID 11120507.

Forney LJ, Foster JA, Ledger W (2006). "The vaginal flora of healthy women is not always dominated by Lactobacillus species". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 194 (10): 1468–9. doi:10.1086/508497. PMID 17054080.

Amaya-Guio J, Viveros-Carreño DA, Sierra-Barrios EM, Martinez-Velasquez MY, Grillo-Ardila CF (October 2016). "Antibiotic treatment for the sexual partners of women with bacterial vaginosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 10: CD011701. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011701.pub2. PMID 27696372.

"STD Facts — Bacterial Vaginosis (BV)". CDC. Archived from the original on 3 December 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

Senok, Abiola C; Verstraelen, Hans; Temmerman, Marleen; Botta, Giuseppe A; Senok, Abiola C (2009). "Probiotics for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD006289. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006289.pub2. PMID 19821358.

Bacterial vaginosis Archived 9 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine from National Health Service, UK. Page last reviewed: 03/10/2013

Hillier, Sharon L.; Nugent, Robert P.; Eschenbach, David A.; Krohn, Marijane A.; Gibbs, Ronald S.; Martin, David H.; Cotch, Mary Frances; Edelman, Robert; Pastorek, Joseph G.; Rao, A. Vijaya; McNellis, Donald; Regan, Joan A.; Carey, J. Christopher; Klebanoff, Mark A. (1995). "Association between Bacterial Vaginosis and Preterm Delivery of a Low-Birth-Weight Infant". New England Journal of Medicine. 333 (26): 1737–1742. doi:10.1056/NEJM199512283332604. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 7491137.

Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL (1991). "Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation". J. Clin. Microbiol. 29 (2): 297–301. PMC 269757. PMID 1706728.

Petrova, Mariya I.; Lievens, Elke; Malik, Shweta; Imholz, Nicole; Lebeer, Sarah (2015). "Lactobacillus species as biomarkers and agents that can promote various aspects of vaginal health". Frontiers in Physiology. 6: 81. doi:10.3389/fphys.2015.00081. ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 4373506. PMID 25859220.

Patterson, J. L.; Stull-Lane, A.; Girerd, P. H.; Jefferson, K. K. (12 November 2009). "Analysis of adherence, biofilm formation and cytotoxicity suggests a greater virulence potential of Gardnerella vaginalis relative to other bacterial-vaginosis-associated anaerobes". Microbiology. 156 (2): 392–399. doi:10.1099/mic.0.034280-0. PMC 2890091. PMID 19910411.

Cottrell BH (2010). "An Updated Review of Evidence to Discourage Douching". MCN, the American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing. 35 (2): 102–107, quiz 107–9. doi:10.1097/NMC.0b013e3181cae9da. PMID 20215951.

Verstraelen H, Delanghe J, Roelens K, Blot S, Claeys G, Temmerman M (2005). "Subclinical iron deficiency is a strong predictor of bacterial vaginosis in early pregnancy". BMC Infect. Dis. 5 (1): 55. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-5-55. PMC 1199597. PMID 16000177. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012.

Nansel TR, Riggs MA, Yu KF, Andrews WW, Schwebke JR, Klebanoff MA (February 2006). "The association of psychosocial stress and bacterial vaginosis in a longitudinal cohort". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194 (2): 381–6. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.047. PMC 2367104. PMID 16458633.

Wilkinson, D; Ramjee, G; Tholandi, M; Rutherford, G (2002). "Nonoxynol-9 for preventing vaginal acquisition of sexually transmitted infections by women from men". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD003939. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003939. PMID 12519623.

Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KC, Eschenbach D, Holmes KK (1983). "Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations". Am. J. Med. 74 (1): 14–22. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. PMID 6600371.

"Diseases Characterized by Vaginal Discharge". cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 11 July 2017.

Donders GG, Vereecken A, Bosmans E, Dekeersmaecker A, Salembier G, Spitz B (January 2002). "Definition of a type of abnormal vaginal flora that is distinct from bacterial vaginosis: aerobic vaginitis". BJOG. 109 (1): 34–43. PMID 11845812.

Workowski KA, Bolan GA (June 2015). "Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015". MMWR Recomm Rep. 64 (RR-03): 1–137. PMC 5885289. PMID 26042815.

"National guideline for the management of bacterial vaginosis (2006)". Clinical Effectiveness Group, British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH). Archived from the original on 3 November 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2008.

Ison CA, Hay PE (2002). "Validation of a simplified grading of Gram stained vaginal smears for use in genitourinary medicine clinics". Sex Transm Infect. 78 (6): 413–5. doi:10.1136/sti.78.6.413. PMC 1758337. PMID 12473800.

Gazi H, Degerli K, Kurt O, Teker A, Uyar Y, Caglar H, Kurutepe S, Surucuoglu S (2006). "Use of DNA hybridization test for diagnosing bacterial vaginosis in women with symptoms suggestive of infection". APMIS. 114 (11): 784–7. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0463.2006.apm_485.x. PMID 17078859.

"Bacterial Vaginosis – CDC Fact Sheet". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 7 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

Mastromarino, Paola; Vitali, Beatrice; Mosca, Luciana (2013). "Bacterial vaginosis: a review on clinical trials with probiotics" (PDF). New Microbiologica. 36 (3): 229–238. PMID 23912864. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 May 2015.

Oduyebo OO, Anorlu RI, Ogunsola FT (2009). Oduyebo OO, ed. "The effects of antimicrobial therapy on bacterial vaginosis in non-pregnant women". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD006055. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006055.pub2. PMID 19588379.

Bradshaw CS, Vodstrcil LA, Hocking JS, Law M, Pirotta M, Garland SM, De Guingand D, Morton AN, Fairley CK (Mar 2013). "Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly associated with posttreatment sexual activities and hormonal contraceptive use". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 56 (6): 777–86. doi:10.1093/cid/cis1030. PMID 23243173.

Lamont, Ronald F.; Nhan-Chang, Chia-Ling; Sobel, Jack D.; Workowski, Kimberly; Conde-Agudelo, Agustin; Romero, Roberto (2011). "Treatment of abnormal vaginal flora in early pregnancy with clindamycin for the prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: a systematic review and metaanalysis". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 205 (3): 177–190. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2011.03.047. ISSN 0002-9378. PMC 3217181. PMID 22071048.

Mehta SD (October 2012). "Systematic review of randomized trials of treatment of male sexual partners for improved bacteria vaginosis outcomes in women". Sex Transm Dis. 39 (10): 822–30. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182631d89. PMID 23007709.

Potter J (November 1999). "Should sexual partners of women with bacterial vaginosis receive treatment?". Br J Gen Pract. 49 (448): 913–8. PMC 1313567. PMID 10818662.

Senok, AC; Verstraelen, H; Temmerman, M; Botta, GA (7 October 2009). "Probiotics for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006289. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006289.pub2. PMID 19821358.

Huang, H; Song, L; Zhao, W (June 2014). "Effects of probiotics for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis in adult women: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 289 (6): 1225–34. doi:10.1007/s00404-013-3117-0. PMID 24318276.

VandeVusse, L; Hanson, L; Safdar, N (2013). "Perinatal outcomes of prenatal probiotic and prebiotic administration: an integrative review". The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing. 27 (4): 288–301, quiz E1–2. doi:10.1097/jpn.0b013e3182a1e15d. PMID 24164813.

Mastromarino P, Vitali B, Mosca L (2013). "Bacterial vaginosis: a review on clinical trials with probiotics". New Microbiol. 36 (3): 229–38. PMID 23912864. |