子宫颈癌是由子宫颈引起的癌症。[1]这是由于细胞的异常生长能够侵入或扩散到身体的其他部位。[11]早期,通常没有出现任何症状。[1]后期症状可能包括阴道异常出血,盆腔疼痛或性交时疼痛。[1]虽然性行为后出血可能不严重,但也可能表明存在宫颈癌。[12]

人乳头瘤病毒感染(HPV)导致超过90%的病例; [4] [5]然而,大多数患有HPV感染的人不会患上宫颈癌。[2] [13]其他风险因素包括吸烟,免疫系统较弱,避孕药,年轻时开始性行为以及有许多性伴侣,但这些不太重要。[1] [3]宫颈癌通常发生在10至20年的癌前变化。[2]大约90%的宫颈癌病例是鳞状细胞癌,10%是腺癌,少数是其他类型。[3]诊断通常通过宫颈筛查然后进行活组织检查。[1]然后进行医学成像以确定癌症是否已经扩散。[1]

HPV疫苗可预防这类病毒的二至七种高风险菌株,并可预防高达90%的宫颈癌。[8] [14] [15]由于存在癌症风险,指南建议继续定期进行巴氏试验。[8]其他预防方法包括很少或没有性伴侣和使用安全套。[7]使用巴氏试验或醋酸进行宫颈癌筛查可以确定癌前病变,治疗后可以预防癌症的发展。[16]宫颈癌的治疗可能包括手术,化疗和放射治疗的某些组合。[1]美国的五年生存率为68%。[17]然而,结果很大程度上取决于癌症检测的早期程度。[3]

在世界范围内,宫颈癌是导致癌症的第四大常见原因,也是女性癌症死亡的第四大常见原因。[2] 2012年,估计发生了528,000例子宫颈癌,其中266,000例死亡。[2]这约占总病例的8%,也是癌症总死亡人数。[18]大约70%的宫颈癌发生在发展中国家,90%发生在死亡中。[2] [19]在低收入国家,它是癌症死亡的最常见原因之一。[16]在发达国家,宫颈癌筛查计划的广泛使用大大降低了宫颈癌的发病率。[20]在医学研究中,最著名的永生化细胞系,即HeLa,是由名为Henrietta Lacks的女性的宫颈癌细胞发展而来的。[21]

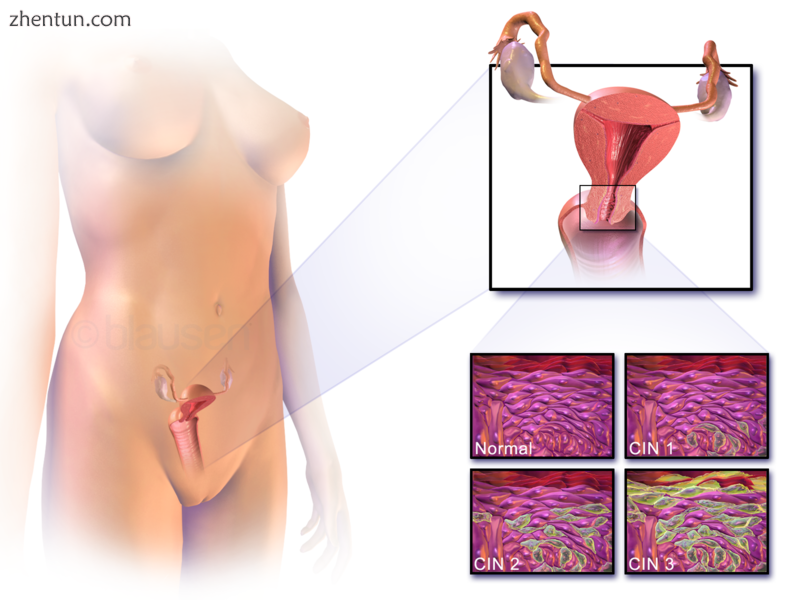

宫颈癌的位置和正常和异常细胞的一个例子

目录

1 症状和体征

2 原因

2.1 人乳头瘤病毒

2.2 吸烟

2.3 口服避孕药

2.4 多胎妊娠

3 诊断

3.1 活检

3.2 癌前病变

3.3 癌症亚型

3.4 分期

4 防治

4.1 筛选

4.2 屏障保护

4.3 预防接种

4.4 营养

5 治疗

6 预后

6.1 阶段

6.2 按国家

7 流行病学

7.1 澳大利亚

7.2 加拿大

7.3 印度

7.4 欧盟

7.5 英国

7.6 美国

8 历史

9 社会与文化

9.1 澳大利亚

9.2 美国

10 参考

体征和症状

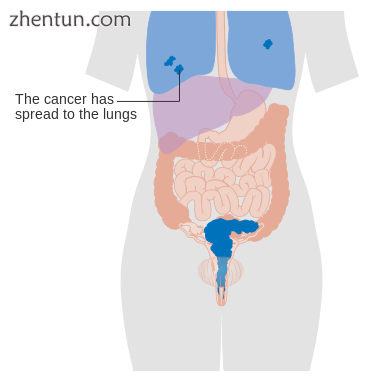

宫颈癌的早期阶段可能完全没有症状。[4] [20]阴道出血,接触性出血(一种最常见的形式是性交后出血),或(很少)阴道肿块可能表明存在恶性肿瘤。此外,性交和阴道分泌物中的中度疼痛是宫颈癌的症状。[22]在晚期疾病中,转移可能存在于腹部,肺部或其他地方。

晚期宫颈癌的症状可能包括:食欲不振,体重减轻,疲劳,骨盆疼痛,背痛,腿痛,腿部肿胀,阴道严重出血,骨折,以及(很少)尿液或粪便从阴道漏出。[23] 冲洗后或盆腔检查后出血是宫颈癌的常见症状。[24]

原因

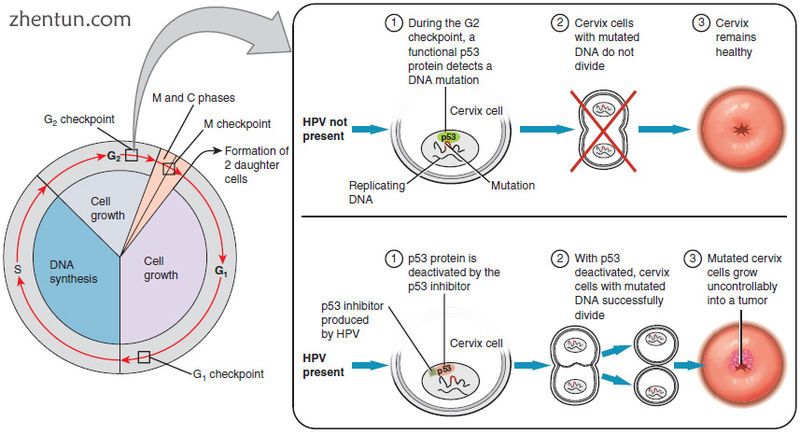

在大多数情况下,感染HPV病毒的细胞会自行愈合。 然而,在某些情况下,病毒继续传播并成为侵袭性癌症。

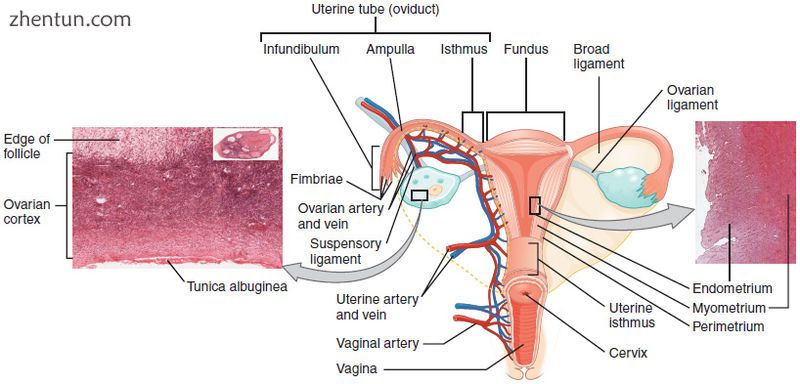

子宫颈相对于阴道上部和子宫后部,显示内部结构覆盖上皮的差异。

某些类型的HPV感染是宫颈癌的最大风险因素,其次是吸烟。[25]艾滋病毒感染也是一个风险因素。[25]然而,并不是所有宫颈癌的原因都已知,并且还涉及其他几个因素。[26] [27]

人乳头瘤病毒

人类乳头瘤病毒16型和18型是全球75%宫颈癌病例的原因,而31和45是另外10%的原因。[28]

与男性发生性关系但有许多其他性伴侣的女性或有许多性伴侣的女性风险更大。[29] [30]

在已知的150-200种HPV中,[31] [32] 15被归类为高风险类型(16,18,31,33,35,39,45,51,52,56,58,59,68) ,73和82),三个可能的高风险(26,53和66),12个低风险(6,11,40,42,43,44,54,61,70,72,81) ,和CP6108)。[33]

生殖器疣是上皮细胞良性肿瘤的一种形式,也是由各种HPV株引起的。然而,这些血清型通常与宫颈癌无关。通常同时存在多种菌株,包括可导致宫颈癌的那些菌株以及引起疣的菌株。

一般认为HPV感染是宫颈癌发生的必要条件。[34]

抽烟

吸烟,无论是主动吸烟还是被动吸烟,都会增加宫颈癌的风险。在HPV感染的女性中,现在和以前的吸烟者患有侵袭性癌症的发病率大约是其两到三倍。被动吸烟也与风险增加有关,但程度较轻。[35]

吸烟也与宫颈癌的发展有关。[36] [37] [38]吸烟可以通过几种不同的方式增加女性的风险,这可以通过直接和间接的方法诱导宫颈癌。[36] [38] [39]感染这种癌症的直接方法是吸烟者发生CIN3的可能性更高,这可能会形成宫颈癌。[36]当CIN3病变导致癌症时,他们中的大多数都有HPV病毒的帮助,但情况并非总是如此,这就是为什么它可以被认为是宫颈癌的直接联系。[39]与轻度吸烟或完全不吸烟相比,大量吸烟和长期吸烟似乎更容易患上CIN3病变。[40]虽然吸烟与宫颈癌有关,但它有助于HPV的发展,HPV是这类癌症的主要原因。[38]此外,它不仅有助于HPV的发展,而且如果女性已经HPV阳性,她患宫颈癌的可能性更大。[40]

口服避孕药

长期使用口服避孕药与宫颈癌风险增加有关。使用口服避孕药5至9年的妇女的侵袭性癌症发病率约为3倍,而使用口服避孕药10年或更长时间的妇女的风险约为4倍。[35]

多次怀孕

许多怀孕与宫颈癌风险增加有关。在HPV感染的女性中,与没有怀孕的女性相比,已经有7次或更多次足月妊娠的女性患癌症的风险是其四倍,而女性患有一到两次足月的风险是其两到三倍的风险怀孕。[35]

诊断

在骨盆的T2加权矢状MR图像上看到宫颈癌

活检

巴氏试验可用作筛查试验,但在多达50%的宫颈癌病例中产生假阴性[41] [42]。其他问题是进行pap测试的成本,这使得它在世界许多地区难以负担。[43]

确认宫颈癌或癌前病变的诊断需要对子宫颈进行活组织检查。这通常通过阴道镜检查来完成,通过使用稀醋酸(例如醋)溶液来强化子宫颈表面异常细胞的子宫颈放大视觉检查,[4]通过染色正常组织提供视觉对比度a桃红色棕色与卢戈的碘。[44]用于子宫颈活组织检查的医疗装置包括穿孔钳等。

阴道镜印象,基于视觉检查的疾病严重程度的估计,构成诊断的一部分。

进一步的诊断和治疗程序是环路电切除手术和宫颈锥切术,其中去除子宫颈的内衬以进行病理学检查。如果活组织检查证实严重的宫颈上皮内瘤变,则进行这些。

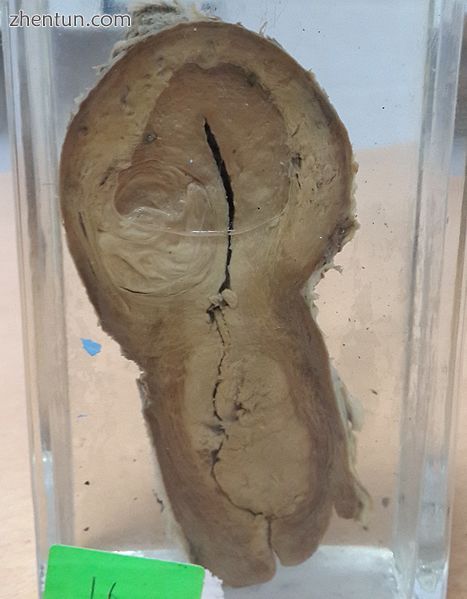

这种大的鳞状癌(图片底部)已经消除了子宫颈并侵入了子宫下段。 子宫也有较高的圆形平滑肌瘤。

通常在活组织检查之前,医生要求医学成像以排除女性症状的其他原因。 已经使用诸如超声,CT扫描和MRI的成像模态来寻找交替的疾病,肿瘤的扩散和对相邻结构的影响。 通常,它们在子宫颈上表现为异质性肿块。[45]

癌前病变

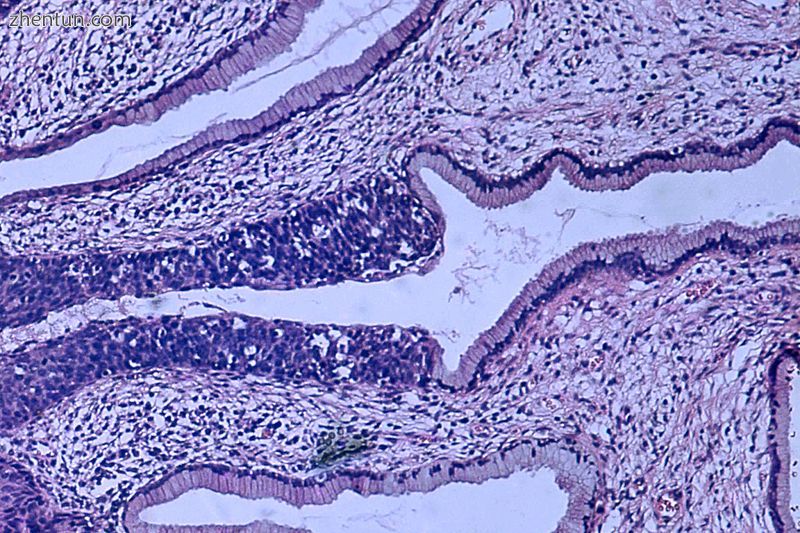

原位癌(也称为CIN III)的组织病理学图像(H&E染色),0期:复层鳞状上皮的正常结构被不规则细胞所取代,这些细胞在其整个厚度上延伸。也可见正常的柱状上皮。

宫颈上皮内瘤变是宫颈癌的潜在前体,通常在病理学家检查宫颈活组织检查时被诊断出来。对于癌前期发育不良变化,使用宫颈上皮内瘤变分级。

宫颈癌前体病变的命名和组织学分类在20世纪已经发生了多次变化。世界卫生组织分类[46] [47]系统描述了病变,将其命名为轻度,中度或严重的不典型增生或原位癌(CIS)。术语宫颈上皮内瘤变(CIN)的开发是为了强调这些病变的异常谱,并有助于标准化治疗。[47]它将轻度不典型增生分为CIN1,中度异常增生为CIN2,严重不典型增生和CIS为CIN3。最近,CIN2和CIN3已合并为CIN2 / 3。这些结果是病理学家可能从活组织检查中报告的结果。

不应将这些与巴氏试​​验(细胞病理学)结果的Bethesda系统术语混淆。在Bethesda结果中:低度鳞状上皮内病变(LSIL)和高级鳞状上皮内病变(HSIL)。 LSIL Pap可以对应于CIN1,HSIL可以对应于CIN2和CIN3,[47]然而,它们是不同测试的结果,并且Pap测试结果不需要与组织学发现相匹配。

癌症亚型

宫颈癌伴子宫肌瘤

浸润性宫颈癌的组织学亚型包括:[48] [49]尽管鳞状细胞癌是发病率最高的宫颈癌,但近几十年来子宫颈腺癌的发病率一直在增加[4]。

鳞状细胞癌(约80-85%[50] [51])

腺癌(约占英国宫颈癌的15%[46])

腺鳞癌

小细胞癌

神经内分泌肿瘤

玻璃样细胞癌

绒毛腺癌

宫颈中很少发生的非癌症恶性肿瘤包括黑素瘤和淋巴瘤。与大多数其他癌症的TNM分期相比,FIGO阶段不包括淋巴结受累。

对于通过手术治疗的病例,从病理学家获得的信息可用于指定单独的病理阶段,但不能替代原始临床阶段。

分期

主要文章:宫颈癌分期

宫颈癌由国际妇产科联合会(FIGO)分期系统进行,该系统基于临床检查而非手术结果。它只允许这些诊断测试用于确定阶段:触诊,检查,阴道镜检查,子宫颈内刮除术,宫腔镜检查,膀胱镜检查,直肠镜检查,静脉尿路造影,肺部和骨骼的X射线检查,以及宫颈锥切术。

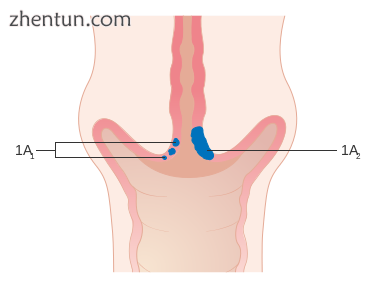

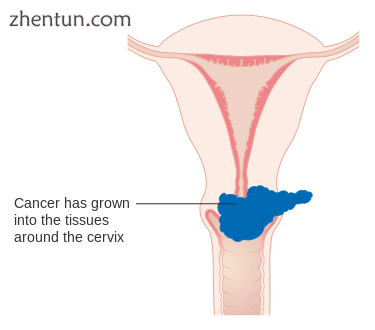

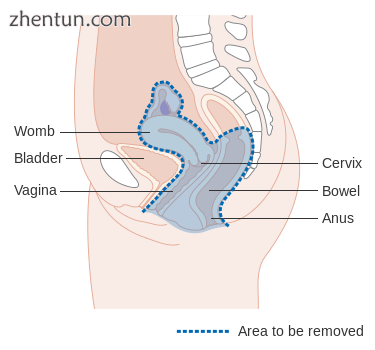

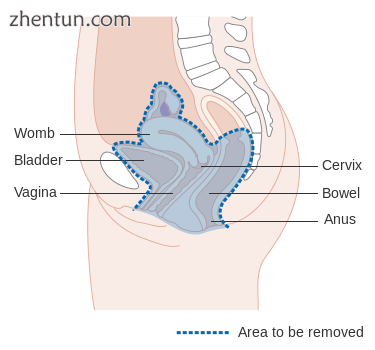

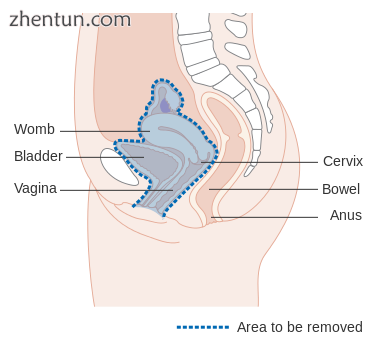

1A期宫颈癌

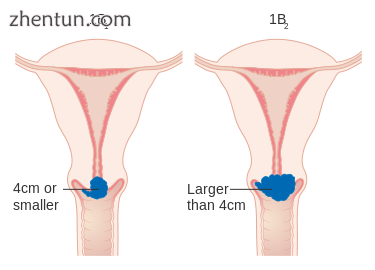

1B期宫颈癌

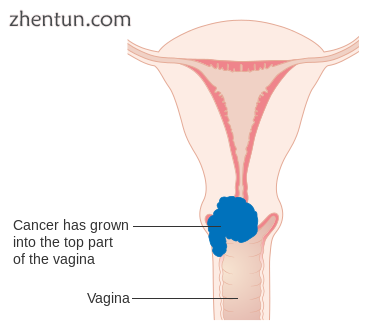

2A期宫颈癌

2B期宫颈癌

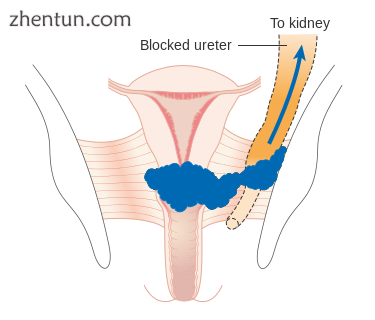

3B期宫颈癌

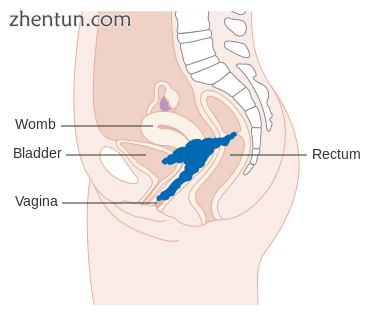

4A期宫颈癌

4B期宫颈癌

预防

筛选

宫颈筛查试验车

用宫颈醋酸进行阴性目测检查

用宫颈乙酸对CIN-1进行阳性目视检查

主要文章:宫颈筛查和巴氏试验

用Papanicolaou试验(宫颈涂片检查)检查子宫颈癌前宫颈细胞,大大减少了宫颈癌的病例数和死亡率。[20]基于液体的细胞学可能会减少样本不足的数量。[52] [53] [54]每三到五年进行一次巴氏试验筛查,并进行适当的随访,可将宫颈癌发病率降低至80%。[55]异常结果可能表明存在癌前病变,允许检查和可能的预防性治疗,称为阴道镜检查。低级病变的治疗可能会对随后的生育能力和怀孕产生不利影响。[35]鼓励妇女接受筛查的个人邀请有效增加了她们这样做的可能性。教育材料也有助于增加妇女进行筛查的可能性,但它们不如邀请有效。[56]

根据2010年欧洲指南,开始筛查的年龄范围在20至30岁之间,但优先于25岁或30岁之前,并且取决于人口中的疾病负担和可用资源。[57 ]

在美国,无论女性开始出现性行为或其他危险因素的年龄,建议从21岁开始进行筛查。[58]巴氏试验应在21至65岁之间每三年进行一次。[58]对于65岁以上的女性,如果在过去10年内未发现异常筛查结果且无CIN 2或更高的病史,则可停止筛查。[58] [59] [60] HPV疫苗接种状态不会改变筛查率。[59]

有许多建议的筛选方法可以筛选那些30至65岁的人。[61]这包括每3年进行一次宫颈细胞学检查,每5年进行一次HPV检测,或者每5年进行一次HPV检测和细胞学检查。[61] [59]由于疾病发病率低,因此在25岁之前进行筛查是没有益处的。如果有超过60岁的女性,如果她们有负面结果,那么筛查就没有益处。[35]美国临床肿瘤学会(ASCO)指南建议不同级别的资源可用性。[62]

巴氏试验在发展中国家并不那么有效。[63]部分原因在于这些国家中的许多国家拥有贫困的医疗保健基础设施,很少有训练有素且技术熟练的专业人员来获取和解释巴氏试验,不知情的女性会因为后续行动而迷失方向,而且需要很长的周转时间来获得结果。 [63]已尝试用醋酸和HPV DNA检测进行目视检查,但结果不尽相同。[63]

屏障保护

在性交过程中使用屏障保护或杀精剂凝胶减少,但不会消除传播感染的风险,[35]虽然安全套可以防止生殖器疣。[64]它们还可以防止其他性传播感染,如艾滋病毒和衣原体感染,这些都与发生宫颈癌的风险增加有关。

疫苗接种

三种HPV疫苗(Gardasil,Gardasil 9和Cervarix)分别使宫颈和会阴癌症或癌前病变的风险降低约93%和62%[65]。疫苗对HPV 16有效率在92%至100%之间,18至18年至少有效。[35]

HPV疫苗通常在9至26岁时给予,因为如果在感染发生之前给予疫苗是最有效的。有效期和是否需要助推器是未知的。这种疫苗的高成本引起了人们的关注。一些国家已经考虑(或正在考虑)为HPV疫苗接种提供资金的计划。美国临床肿瘤学会(ASCO)指南针对不同级别的资源可用性提出了建议。[66]

自2010年以来,日本的年轻女性有资格免费接种宫颈癌疫苗。[67] 2013年6月,日本厚生劳动省要求,在实施疫苗之前,医疗机构必须告知妇女该部不推荐疫苗。[67] 但是,对于选择接种疫苗的日本女性来说,疫苗仍可免费获得。[67]

营养

维生素A和维生素B12,维生素C,维生素E和β-胡萝卜素的风险较低[68]。[69]

治疗

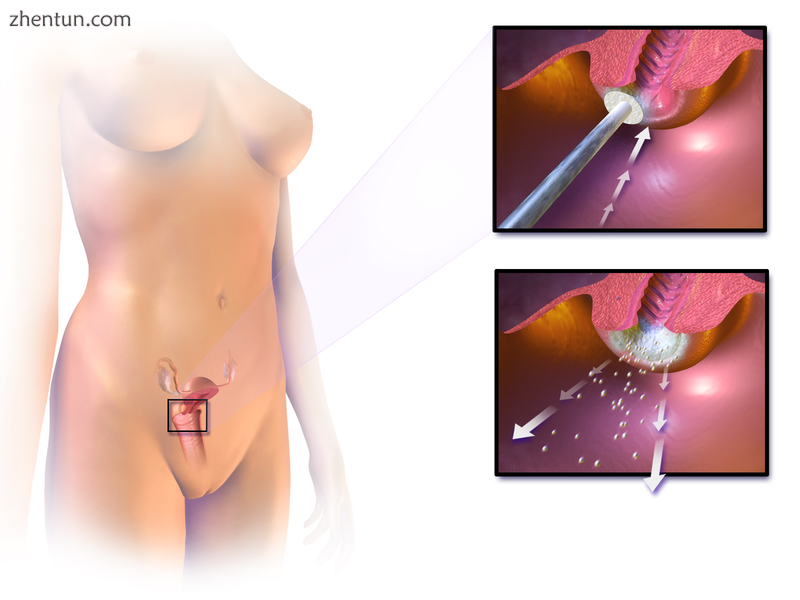

宫颈冷冻疗法

宫颈癌的治疗方法在世界范围内各不相同,主要是由于接受了根治性盆腔手术技术的外科医生,以及发达国家出现了保留生育能力的治疗方法。由于宫颈癌具有放射敏感性,因此可以在不存在手术选择的所有阶段使用放射线。外科手术干预可能比放射学方法有更好的结果。[70]此外,化疗可用于治疗宫颈癌,并且已被发现比单独放射疗法更有效。[71]

微创癌(IA期)可通过子宫切除术(切除整个子宫,包括部分阴道)进行治疗。[需要引证]对于IA2期,也切除淋巴结。替代方案包括局部外科手术,如环路电切除手术或锥形活检。[72] [73]

如果锥形活组织检查不能产生明显的边缘[74](活检结果显示肿瘤被无癌组织包围,表明所有肿瘤都被切除),对于想要保持生育能力的女性来说,另一种可能的治疗选择是:切除术。[75]这试图在保留卵巢和子宫的同时手术切除癌症,提供比子宫切除术更保守的手术。对于那些尚未扩散的I期宫颈癌患者来说,这是一个可行的选择;然而,它尚未被视为一种护理标准,[76]因为很少有医生熟练掌握这一程序。即使是最有经验的外科医生也不能保证在手术显微镜检查之后可以进行气管切除术,因为癌症扩散的程度尚不清楚。如果一旦妇女在手术室中进行全身麻醉,外科医生无法在显微镜下确认明显的宫颈组织边缘,则仍可能需要进行子宫切除术。只有在事先同意的情况下,才能在同一手术中进行此操作。由于癌症可能在1b期癌症和某些1a期癌症中扩散到淋巴结的风险,外科医生可能还需要从子宫周围移除一些淋巴结进行病理评估。

根治性膀胱切除术可以在腹部[77]或阴道[78]进行,并且意见相互矛盾,哪种情况更好。[79]淋巴结切除术的根治性腹部切除术通常只需要住院两到三天,大多数女性恢复得非常快(大约六周)。并发症并不常见,尽管手术后能够怀孕的女性容易早产和可能晚期流产。[80]在手术后尝试怀孕之前,通常建议至少等待一年。[81]如果癌症已通过气管切除术清除,则残留子宫颈复发非常罕见。[76]然而,建议女性实施警惕预防和后续护理,包括巴氏筛查/阴道镜检查,根据需要对其余子宫下段进行活组织检查(每3-4个月至少5年),以监测任何复发除了通过安全的性行为减少任何新的HPV暴露,直到一个人积极尝试怀孕。

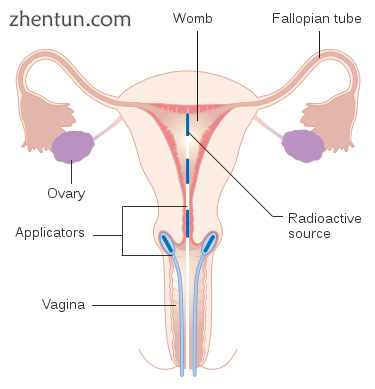

早期阶段(IB1和IIA小于4 cm)可以通过根治性子宫切除术治疗,同时切除淋巴结或放射治疗。 放射治疗作为骨盆和近距离放射治疗(内部放射)的外部束放射治疗给予。 在病理检查中发现具有高风险特征的手术治疗的妇女,无论是否接受化疗,均接受放射治疗,以降低复发风险。

近距离放射治疗宫颈癌

较大的早期肿瘤(IB2和IIA超过4 cm)可以用放射疗法和基于顺铂的化学疗法,子宫切除术(其通常需要辅助放射疗法),或顺铂化学疗法然后进行子宫切除术来治疗。当顺铂存在时,它被认为是周期性疾病中最活跃的单一药物。[82]这种基于铂的化学疗法加入化学放射治疗似乎不仅可以提高生存率,还可以降低早期宫颈癌(IA2-IIA)女性的复发风险。[83]

晚期肿瘤(IIB-IVA)用放射疗法和基于顺铂的化学疗法治疗。 2006年6月15日,美国食品和药物管理局批准将两种化疗药物hycamtin和顺铂联合用于晚期(IVB)宫颈癌治疗的女性。[84]联合治疗具有中性粒细胞减少,贫血和血小板减少症副作用的显著风险。[引证需要]

对于手术治疗,必须切除整个癌症,在显微镜下检查时,在移除的组织边缘没有发现癌症。[85]这个程序被称为剜除术。[85]

图显示通过后路手术切除的区域

该图显示了通过总操作移除的区域

图表显示通过前路手术切除的区域

预测

阶段

预后取决于癌症的阶段。对于患有微观形式宫颈癌的女性,存活率接近100%。[86]通过治疗,浸润性宫颈癌最早阶段的5年相对存活率为92%,而总体(所有阶段合并)的5年生存率约为72%。这些统计数据在应用于新诊断的妇女时可能会得到改善,同时考虑到这些结果可能部分取决于五年前首次诊断为女性时的治疗状况。[87]

通过治疗,80-90%的患有I期癌症的女性和60-75%的患有II期癌症的女性在诊断后5年存活。在诊断后五年,III期癌症患者的生存率降至30-40%,IV期患者的生存率降低15%或更少[88]。在其早期阶段检测到的复发性宫颈癌可以通过手术,放射,化学疗法或三者的组合成功治疗。大约35%的浸润性宫颈癌女性在治疗后患有持续性或复发性疾病。[89]

按国家

美国白人女性的五年生存率为69%,黑人女性的五年生存率为57%。[90]

定期筛查意味着早期发现并治疗了癌前病变和早期宫颈癌。数据表明,通过预防宫颈癌,宫颈筛查每年可以挽救5000人的生命。[91]在英国,每年约有1,000名女性死于宫颈癌。所有北欧国家都制定了宫颈癌筛查计划。[92]巴氏试验在20世纪60年代被纳入北欧国家的临床实践。[92]

在非洲,由于诊断经常处于疾病的后期,因此结果往往更糟。[93]

流行病学

2004年每10万居民死于宫颈癌的年龄标准化死亡率[94]

![Age-standardized death from cervical cancer per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004[94].jpg Age-standardized death from cervical cancer per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004[94].jpg](data/attachment/forum/201908/01/204202zb1ov1oo6kow6hvd.jpg)

在世界范围内,宫颈癌是女性癌症和癌症死亡的第四大常见原因。[2] 2018年,估计发生了570,000例子宫颈癌,死亡人数超过300,000例。[95]它是乳腺癌后女性特异性癌症的第二大常见原因,占癌症总数和女性癌症总死亡人数的8%左右。[18]大约80%的宫颈癌发生在发展中国家。[96]它是怀孕期间最常检测到的癌症,每10万次怀孕发生率为1.5至12次。[97]

澳大利亚

2005年,澳大利亚共有734例宫颈癌。自1991年(1991-2005)开始组织筛查以来,每年诊断为宫颈癌的妇女人数平均下降4.5%。[98]定期每年两次的巴氏试验可以使澳大利亚的宫颈癌发病率降低90%,并且每年有1,200名澳大利亚妇女免于死于该疾病。[99]据预测,由于主要HPV检测计划的成功,到2028年,每年每100 000名妇女的新病例将少于四例。[100]

加拿大

在加拿大,估计2008年将有1,300名妇女被诊断患有宫颈癌,其中380人将死亡。[101]

印度

在印度,患有子宫颈癌的人数正在上升,但总体而言,年龄调整率正在下降。[102]在女性人群中使用安全套可以提高宫颈癌患者的生存率。[103]

欧洲联盟

在欧洲联盟,2004年每年约有34,000例新发病例和16,000例宫颈癌死亡病例。[55]

英国

宫颈癌是英国女性中第12位最常见的癌症(2011年约有3,100名女性被诊断患有此病),占癌症死亡人数的1%(2012年约有920人死亡)。[104]从1988年至1997年减少42%,NHS实施的筛查计划非常成功,每3年筛查风险最高的年龄组(25-49岁),每5年筛查50-64岁。

美国

据估计,2019年美国将发生13,170例新的宫颈癌和4,250例宫颈癌死亡病例。[105]诊断的中位年龄为50岁。根据2012 - 2016年的比率,美国新发病例的比例为每10万名妇女7.3例。在过去的50年中,宫颈癌死亡人数减少了约74%,这主要是由于巴氏试验筛查的普遍存在。[106]在引入HPV疫苗之前,宫颈癌预防和治疗的年度直接医疗费用估计为60亿美元。[106]

历史

另见:宫颈癌的时间表

公元前400年 - 希波克拉底指出宫颈癌是无法治愈的

1925年 - Hinselmann发明了阴道镜

1928年 - Papanicolaou开发了Papanicolaou技术

1941年 - Papanicolaou和Traut:Pap测试筛选开始了

1946年 - 开发艾尔斯伯里刮刀刮除子宫颈,收集样本进行巴氏试验

1951年 - 第一个成功的体外细胞系HeLa,来源于Henrietta Lacks宫颈癌的活检

1976年 - Harald zur Hausen和Gisam在宫颈癌和生殖器疣中发现HPV DNA; Hausen后来因其工作获得诺贝尔奖[107]

1988年 - 用于报告Pap结果的Bethesda系统得以开发

2006年 - 第一台HPV疫苗获得了FDA的批准

2015年 - HPV疫苗显示可防止多个身体部位感染[108]

2018年 - 使用HPV疫苗进行单剂量保护的证据[109]

在20世纪初工作的流行病学家指出,宫颈癌的表现就像性传播疾病。综上所述:

宫颈癌在女性性工作者中很常见。

在修女中很少见,除了那些在进入修道院之前曾经过性活跃的人。 (Rigoni于1841年)

在第一个妻子死于宫颈癌的男人的第二个妻子中更为常见。

这在犹太妇女中很少见。[110]

1935年,Syverton和Berry发现了RPV(兔乳头瘤病毒)与兔皮肤癌之间的关系。 (HPV是物种特异性的,因此不能传染给兔子)

这些历史观察表明宫颈癌可能是由性传播剂引起的。 20世纪40年代和50年代的初步研究将宫颈癌归为包皮垢(例如Heins等,1958)。[111]在20世纪60年代和70年代,人们怀疑单纯疱疹病毒感染是导致这种疾病的原因。总之,HSV被认为是一个可能的原因,因为它已知在女性生殖道中存活,以与已知风险因素相容的方式进行性传播,例如滥交和低社会经济地位。[112]疱疹病毒还涉及其他恶性疾病,包括伯基特淋巴瘤,鼻咽癌,马立克氏病和幸运肾腺癌。从宫颈肿瘤细胞中回收HSV。

1949年通过电子显微镜对人乳头瘤病毒(HPV)进行了描述,并于1963年鉴定了HPV-DNA。[113]直到20世纪80年代,HPV才在宫颈癌组织中被发现。[114]从那以后,已经证明HPV几乎涉及所有宫颈癌。[115]涉及的特定病毒亚型是HPV16,18,31,45等。

在1980年代中期开始的工作中,HPV疫苗由乔治敦大学医学中心,罗切斯特大学,澳大利亚昆士兰大学和美国国家癌症研究所的研究人员同时开发。[116] 2006年,美国食品和药物管理局(FDA)批准了第一种预防性HPV疫苗,由Merck&Co。以商品名Gardasil销售。

社会与文化

澳大利亚

在澳大利亚,土著妇女死于子宫颈癌的可能性是非土著妇女的五倍以上,这表明土著妇女不太可能接受定期的巴氏试验。[117]有几个因素可能限制土著妇女参与定期的子宫颈筛查做法,包括在土著社区讨论这一主题时的敏感性,尴尬,焦虑和对程序的恐惧。[118]难以获得筛查服务(例如运输困难)和缺乏女性全科医生,经过培训的巴氏检测提供者和训练有素的女性土著卫生工作者也是问题。[118]

澳大利亚宫颈癌基金会(ACCF)成立于2008年,在澳大利亚和发展中国家通过消除子宫颈癌和为患有宫颈癌和相关健康问题的妇女提供治疗来促进“妇女的健康”。[119] Ian Frazer,其中一个Gardasil宫颈癌疫苗的开发者,是ACCF的科学顾问。[120]澳大利亚前总理约翰霍华德的妻子珍妮特霍华德于1996年被诊断患有宫颈癌,并于2006年首次谈及她与该疾病的斗争。[121]

美国

2007年对美国女性进行的一项调查显示,40%的人听说过HPV感染,不到一半的人知道它会导致宫颈癌。[122]经过1975年至2000年的纵向研究,发现社会经济普查较低的人群晚期癌症诊断率较高,发病率较高。控制阶段后,存活率仍然存在差异。[123]

参考:

"Cervical Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". NCI. 2014-03-14. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.12. ISBN 978-9283204299.

"Cervical Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". National Cancer Institute. 2014-03-14. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell RN (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. pp. 718–721. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1.

Kufe, Donald (2009). Holland-Frei cancer medicine (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 1299. ISBN 9781607950141. Archived from the original on 2015-12-01.

Bosch, FX; de Sanjosé, S (2007). "The epidemiology of human papillomavirus infection and cervical cancer". Disease Markers. 23 (4): 213–27. doi:10.1155/2007/914823. PMC 3850867. PMID 17627057.

"Cervical Cancer Prevention (PDQ®)". National Cancer Institute. 2014-02-27. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

"Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines". National Cancer Institute. 2011-12-29. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

"Global Cancer Facts & Figures 3rd Edition" (PDF). 2015. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-22. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

Bray, Freddie; Ferlay, Jacques; Soerjomataram, Isabelle; Siegel, Rebecca L.; Torre, Lindsey A.; Jemal, Ahmedin (2018). "Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 68 (6): 394–424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492. ISSN 0007-9235. PMID 30207593.

"Defining Cancer". National Cancer Institute. 2007-09-17. Archived from the original on 25 June 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

Tarney, CM; Han, J (2014). "Postcoital bleeding: a review on etiology, diagnosis, and management". Obstetrics and Gynecology International. 2014: 192087. doi:10.1155/2014/192087. PMC 4086375. PMID 25045355.

Dunne, EF; Park, IU (Dec 2013). "HPV and HPV-associated diseases". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 27 (4): 765–78. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2013.09.001. PMID 24275269.

"FDA approves Gardasil 9 for prevention of certain cancers caused by five additional types of HPV". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 10 December 2014. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

Tran, NP; Hung, CF; Roden, R; Wu, TC (2014). Control of HPV infection and related cancer through vaccination. Recent Results in Cancer Research. 193. pp. 149–71. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-38965-8_9. ISBN 978-3-642-38964-1. PMID 24008298.

World Health Organization (February 2014). "Fact sheet No. 297: Cancer". Archived from the original on 2014-02-13. Retrieved 2014-06-24.

"SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Cervix Uteri Cancer". NCI. National Cancer Institute. November 10, 2014. Archived from the original on 6 July 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 1.1. ISBN 978-9283204299.

"Cervical cancer prevention and control saves lives in the Republic of Korea". World Health Organization. Retrieved 1 November 2018.

Canavan TP, Doshi NR (2000). "Cervical cancer". Am Fam Physician. 61 (5): 1369–76. PMID 10735343. Archived from the original on 2005-02-06.

Jr, Charles E. Carraher (2014). Carraher's polymer chemistry (Ninth ed.). Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis. p. 385. ISBN 9781466552036. Archived from the original on 2015-10-22.

"Cervical Cancer Symptoms, Signs, Causes, Stages & Treatment". medicinenet.com.

Nanda, Rita (2006-06-09). "Cervical cancer". MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

"Cervical Cancer Prevention and Early Detection". Cancer. Archived from the original on 2015-07-10.

Gadducci A, Barsotti C, Cosio S, Domenici L, Riccardo Genazzani A (2011). "Smoking habit, immune suppression, oral contraceptive use, and hormone replacement therapy use and cervical carcinogenesis: A review of the literature". Gynecological Endocrinology. 27 (8): 597–604. doi:10.3109/09513590.2011.558953. PMID 21438669.

Stuart Campbell; Ash Monga (2006). Gynaecology by Ten Teachers (18 ed.). Hodder Education. ISBN 978-0-340-81662-2.

"Cervical Cancer Symptoms, Signs, Causes, Stages & Treatment". medicinenet.com.

Dillman, edited by Robert K. Oldham, Robert O. (2009). Principles of cancer biotherapy (5th ed.). Dordrecht: Springer. p. 149. ISBN 9789048122899. Archived from the original on 2015-10-29.

"What Causes Cancer of the Cervix?". American Cancer Society. 2006-11-30. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

Marrazzo JM, Koutsky LA, Kiviat NB, Kuypers JM, Stine K (2001). "Papanicolaou test screening and prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among women who have sex with women". Am J Public Health. 91 (6): 947–52. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.6.947. PMC 1446473. PMID 11392939.

"HPV Type-Detect". Medical Diagnostic Laboratories. 2007-10-30. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

Gottlieb, Nicole (2002-04-24). "A Primer on HPV". Benchmarks. National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 2007-10-26. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, Herrero R, Castellsagué X, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Meijer CJ (2003). "Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 348 (6): 518–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021641. hdl:2445/122831. PMID 12571259.

Snijders PJ, Steenbergen RD, Heideman DA, Meijer CJ (2006). "HPV-mediated cervical carcinogenesis: concepts and clinical implications". J. Pathol. 208 (2): 152–64. doi:10.1002/path.1866. PMID 16362994.

National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute: PDQ® Cervical Cancer Prevention Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Date last modified 05/01/2010. Accessed 06/04/2019.

Luhn P, Walker J, Schiffman M, Zuna RE, Dunn ST, Gold MA, Smith K, Mathews C, Allen RA, Zhang R, Wang S, Wentzensen N (2013). "The role of co-factors in the progression from human papillomavirus infection to cervical cancer". Gynecologic Oncology. 128 (2): 265–270. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.11.003. ISSN 0090-8258. PMC 4627848. PMID 23146688.

Remschmidt C, Kaufmann AM, Hagemann I, Vartazarova E, Wichmann O, Deleré Y (2013). "Risk Factors for Cervical Human Papillomavirus Infection and High-Grade Intraepithelial Lesion in Women Aged 20 to 31 Years in Germany". International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 23 (3): 519–526. doi:10.1097/IGC.0b013e318285a4b2. ISSN 1048-891X. PMID 23360813.

Gadducci A, Barsotti C, Cosio S, Domenici L, Riccardo Genazzani A (2011). "Smoking habit, immune suppression, oral contraceptive use, and hormone replacement therapy use and cervical carcinogenesis: a review of the literature". Gynecological Endocrinology. 27 (8): 597–604. doi:10.3109/09513590.2011.558953. ISSN 0951-3590. PMID 21438669.

Agorastos T, Miliaras D, Lambropoulos AF, Chrisafi S, Kotsis A, Manthos A, Bontis J (2005). "Detection and typing of human papillomavirus DNA in uterine cervices with coexistent grade I and grade III intraepithelial neoplasia: biologic progression or independent lesions?". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 121 (1): 99–103. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.024. ISSN 0301-2115. PMID 15949888.

Jensen KE, Schmiedel S, Frederiksen K, Norrild B, Iftner T, Kjær SK (2012). "Risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse in relation to smoking among women with persistent human papillomavirus infection". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 21 (11): 1949–55. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0663. PMC 3970163. PMID 23019238.

Cecil Medicine: Expert Consult Premium Edition . ISBN 1437736084, 9781437736083. Page 1317.

Berek and Hacker's Gynecologic Oncology. ISBN 0781795125, 9780781795128. Page 342

Cronjé, H.S. (February 2004). "Screening for cervical cancer in developing countries". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 84 (2): 101–108. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2003.09.009. PMC 1882302. PMID 14871510.

Sellors, JW (2003). "Chapter 4: An introduction to colposcopy: indications for colposcopy, instrumentation, principles and documentation of results". Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a beginners' manual. ISBN 978-92-832-0412-1.

H. K. Pannu; F. M. Corl; E. K. Fishman (September–October 2001). "CT evaluation of cervical cancer: spectrum of disease". Radiographics. 21 (5): 1155–1168. doi:10.1148/radiographics.21.5.g01se311155. PMID 11553823.

"Cancer Research UK website". Archived from the original on 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

DeMay, M (2007). Practical principles of cytopathology. Revised edition. Chicago, IL: American Society for Clinical Pathology Press. ISBN 978-0-89189-549-7.

Garcia A, Hamid O, El-Khoueiry A (2006-07-06). "Cervical Cancer". eMedicine. WebMD. Archived from the original on 2007-12-09. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

Dolinsky, Christopher (2006-07-17). "Cervical Cancer: The Basics". OncoLink. Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 2008-01-18. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

"What Is Cervical Cancer?". American Cancer Society.

"Cervical cancer – Types and grades". Cancer Research UK.

Payne N, Chilcott J, McGoogan E (2000). "Liquid-based cytology in cervical screening: a rapid and systematic review". Health Technology Assessment. 4 (18): 1–73. PMID 10932023. Archived from the original on 2011-06-11.

Karnon J, Peters J, Platt J, Chilcott J, McGoogan E, Brewer N (May 2004). "Liquid-based cytology in cervical screening: an updated rapid and systematic review and economic analysis". Health Technology Assessment. 8 (20): iii, 1–78. doi:10.3310/hta8200. PMID 15147611.

"Liquid Based Cytology (LBC): NHS Cervical Screening Programme". Archived from the original on 2011-01-08. Retrieved 2010-10-01.

Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, Ronco G, Schenck U, Segnan N, Wiener H, Herbert A, von Karsa L (2010). "European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening. Second Edition—Summary Document". Annals of Oncology. 21 (3): 448–458. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp471. PMC 2826099. PMID 20176693.

Everett T, Bryant A, Griffin MF, Martin-Hirsch PP, Forbes CA, Jepson RG (2011). Everett T (ed.). "Interventions targeted at women to encourage the uptake of cervical screening". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (5): CD002834. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002834.pub2. PMC 4163962. PMID 21563135.

Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, Ronco G, Schenck U, Segnan N, Wiener H, Herbert A, von Karsa L (Mar 2010). "European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Cervical Cancer Screening. Second edition—summary document". Annals of Oncology. 21 (3): 448–58. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdp471. PMC 2826099. PMID 20176693.

"Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines for Average-Risk Women" (PDF). cdc.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 February 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2014.

Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology (Nov 2012). "ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 131: Screening for cervical cancer". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 120 (5): 1222–38. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e318277c92a (inactive 2019-02-10). PMID 23090560.

Karjane N, Chelmow D (June 2013). "New cervical cancer screening guidelines, again". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 40 (2): 211–23. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2013.03.001. PMID 23732026.

Curry, Susan J.; Krist, Alex H.; Owens, Douglas K.; Barry, Michael J.; Caughey, Aaron B.; Davidson, Karina W.; Doubeni, Chyke A.; Epling, John W.; Kemper, Alex R.; Kubik, Martha; Landefeld, C. Seth; Mangione, Carol M.; Phipps, Maureen G.; Silverstein, Michael; Simon, Melissa A.; Tseng, Chien-Wen; Wong, John B. (21 August 2018). "Screening for Cervical Cancer". JAMA. 320 (7): 674–686. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.10897. PMID 30140884.

Arrossi, Silvina; Temin, Sarah; Garland, Suzanne; Eckert, Linda O'Neal; Bhatla, Neerja; Castellsagué, Xavier; Alkaff, Sharifa Ezat; Felder, Tamika; Hammouda, Doudja; Konno, Ryo; Lopes, Gilberto; Mugisha, Emmanuel; Murillo, Rául; Scarinci, Isabel C.; Stanley, Margaret; Tsu, Vivien; Wheeler, Cosette M.; Adewole, Isaac Folorunso; De Sanjosé, Silvia (2017). "Primary Prevention of Cervical Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Resource-Stratified Guideline: Journal of Global Oncology: Vol 0, No 0". Journal of Global Oncology. 3 (5): 611–634. doi:10.1200/JGO.2016.008151. PMC 5646902. PMID 29094100.

World Health Organization (2014). Comprehensive cervical cancer control. A guide to essential practice - Second edition. ISBN 978-92-4-154895-3. Archived from the original on 2015-05-04.

Manhart LE, Koutsky LA (2002). "Do condoms prevent genital HPV infection, external genital warts, or cervical neoplasia? A meta-analysis". Sex Transm Dis. 29 (11): 725–35. doi:10.1097/00007435-200211000-00018. PMID 12438912.

Medeiros LR, Rosa DD, da Rosa MI, Bozzetti MC, Zanini RR (2009). "Efficacy of Human Papillomavirus Vaccines". International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 19 (7): 1166–76. doi:10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a3d100. PMID 19823051.

Arrossi, Silvina; Temin, Sarah; Garland, Suzanne; Eckert, Linda O'Neal; Bhatla, Neerja; Castellsagué, Xavier; Alkaff, Sharifa Ezat; Felder, Tamika; Hammouda, Doudja; Konno, Ryo; Lopes, Gilberto; Mugisha, Emmanuel; Murillo, Rául; Scarinci, Isabel C.; Stanley, Margaret; Tsu, Vivien; Wheeler, Cosette M.; Adewole, Isaac Folorunso; De Sanjosé, Silvia (2017). "Primary Prevention of Cervical Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Resource-Stratified Guideline: Journal of Global Oncology: Vol 0, No 0". Journal of Global Oncology. 3 (5): 611–634. doi:10.1200/JGO.2016.008151. PMC 5646902. PMID 29094100.

The Asahi Shimbun (15 June 2013). "Health ministry withdraws recommendation for cervical cancer vaccine". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013.

Zhang X, Dai B, Zhang B, Wang Z (2011). "Vitamin A and risk of cervical cancer: A meta-analysis". Gynecologic Oncology. 124 (2): 366–73. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.10.012. PMID 22005522.

Myung SK, Ju W, Kim SC, Kim H (2011). "Vitamin or antioxidant intake (or serum level) and risk of cervical neoplasm: A meta-analysis". BJOG. 118 (11): 1285–91. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03032.x. PMID 21749626.

Baalbergen, Astrid; Veenstra, Yerney; Stalpers, Lukas; Baalbergen, Astrid (2013). "Primary surgery versus primary radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy for early adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix". Reviews (1): CD006248. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006248.pub3. PMID 23440805.

Einhorn, N; Tropé, C; Ridderheim, M; Boman, K; Sorbe, B; Cavallin-Ståhl, E (2003). "A systematic overview of radiation therapy effects in cervical cancer (cervix uteri)". Acta Oncologica. 42 (5–6): 546–56. doi:10.1080/02841860310014660. PMID 14596512.

Erstad, Shannon (2007-01-12). "Cone biopsy (conization) for abnormal cervical cell changes". WebMD. Archived from the original on 2007-11-19. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

Lin, Yanying; Zhou, Jingyi; Dai, Lin; Cheng, Yuan; Wang, Jianliu (2017). "Vaginectomy and vaginoplasty for isolated vaginal recurrence 8 years after cervical cancer radical hysterectomy: A case report and literature review". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 43 (9): 1493–1497. doi:10.1111/jog.13375. ISSN 1341-8076. PMID 28691384.

Jones WB, Mercer GO, Lewis JL, Rubin SC, Hoskins WJ (1993). "Early invasive carcinoma of the cervix". Gynecol. Oncol. 51 (1): 26–32. doi:10.1006/gyno.1993.1241. PMID 8244170.

Dolson, Laura (2001). "Trachelectomy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

Burnett AF (2006). "Radical trachelectomy with laparoscopic lymphadenectomy: review of oncologic and obstetrical outcomes". Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 18 (1): 8–13. doi:10.1097/01.gco.0000192968.75190.dc. PMID 16493253.

Cibula D, Ungár L, Svárovsky J, Zivny J, Freitag P (2005). "[Abdominal radical trachelectomy—technique and experience]". Ceska Gynekol (in Czech). 70 (2): 117–22. PMID 15918265.

Plante M, Renaud MC, Hoskins IA, Roy M (2005). "Vaginal radical trachelectomy: a valuable fertility-preserving option in the management of early-stage cervical cancer. A series of 50 pregnancies and review of the literature". Gynecol. Oncol. 98 (1): 3–10. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.04.014. PMID 15936061.

Roy M, Plante M, Renaud MC, Têtu B (1996). "Vaginal radical hysterectomy versus abdominal radical hysterectomy in the treatment of early-stage cervical cancer". Gynecol. Oncol. 62 (3): 336–9. doi:10.1006/gyno.1996.0245. PMID 8812529.

Dargent D, Martin X, Sacchetoni A, Mathevet P (2000). <1877::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-W/pdf "Laparoscopic vaginal radical trachelectomy: a treatment to preserve the fertility of cervical carcinoma patients". Cancer. 88 (8): 1877–82. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000415)88:8<1877::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID 10760765.

Schlaerth JB, Spirtos NM, Schlaerth AC (2003). "Radical trachelectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy with uterine preservation in the treatment of cervical cancer". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 188 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.124. PMID 12548192.

Waggoner, Steven E (2003). "Cervical Cancer". The Lancet. 361 (9376): 2217–25. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13778-6. PMID 12842378.

Falcetta, FS; Medeiros, LR; Edelweiss, MI; Pohlmann, PR; Stein, AT; Rosa, DD (22 November 2016). "Adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy for early stage cervical cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD005342. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005342.pub4. PMC 4164460. PMID 27873308.

"FDA Approves First Drug Treatment for Late-Stage Cervical Cancer". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2006-06-15. Archived from the original on 2007-10-10. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

Sardain, H; Lavoue, V; Redpath, M; Bertheuil, N; Foucher, F; Levêque, J (August 2015). "Curative pelvic exenteration for recurrent cervical carcinoma in the era of concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy. A systematic review" (PDF). European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 41 (8): 975–85. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2015.03.235. PMID 25922209.

"Cervical Cancer". Encyclopedia of Women's Health.

"What Are the Key Statistics About Cervical Cancer?". American Cancer Society. 2006-08-04. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

"Cervical Cancer". Cervical Cancer: Cancers of the Female Reproductive System: Merck Manual Home Edition. Merck Manual Home Edition. Archived from the original on 2006-12-16. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

"Cervical Cancer". Cervical Cancer: Pathology, Symptoms and Signs, Diagnosis, Prognosis and Treatment. Armenian Health Network, Health.am. Archived from the original on 2007-02-07.

"Cervical Cancer: Statistics | Cancer.Net". Cancer.Net. 2012-06-25. Archived from the original on 2017-08-27. Retrieved 2017-08-27.

"Cervical cancer statistics and prognosis". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 2007-05-20. Retrieved 2007-03-24.

Nygård M (2011). "Screening for cervical cancer: When theory meets reality". BMC Cancer. 11: 240. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-11-240. PMC 3146446. PMID 21668947.

Muliira, RS; Salas, AS; O'Brien, B (2016). "Quality of Life among Female Cancer Survivors in Africa: An Integrative Literature Review". Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing. 4 (1): 6–17. doi:10.4103/2347-5625.199078. PMC 5297234. PMID 28217724.

"WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-11-11. Retrieved Nov 11, 2009.

"WHO Fact Sheet on HPV and Cervical Cancer". World Health Organization. 2018-01-24. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

Kent A (Winter 2010). "HPV Vaccination and Testing". Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 3 (1): 33–4. PMC 2876324. PMID 20508781.

Cordeiro, Christina N.; Gemignani, Mary L. (2017). "Gynecologic Malignancies in Pregnancy". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 72 (3): 184–193. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000407. ISSN 0029-7828. PMC 5358514. PMID 28304416.

"Incidence and mortality rates". Archived from the original on 2009-09-12.

"Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-03-14. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

Hall, Michaela; et al. (2 October 2018). "The projected timeframe until cervical cancer elimination in Australia: a modelling study". Lancet. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

MacDonald N, Stanbrook MB, Hébert PC (September 2008). "Human papillomavirus vaccine risk and reality". CMAJ (in French). 179 (6): 503, 505. doi:10.1503/cmaj.081238. PMC 2527393. PMID 18762616.

National Cancer Registry Programme under Indian Council of Medical Research Reports

Krishnatreya, M; Kataki, AC; Sharma, JD; Nandy, P; Gogoi, G (2015). "Association of educational levels with survival in Indian patients with cancer of the uterine cervix". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 16 (8): 3121–3. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.8.3121. PMID 25921107.

"Cervical cancer statistics". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

"Cancer Stat Facts: Cervical Cancer". National Cancer Institute SEER Program. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

Armstrong EP (April 2010). "Prophylaxis of Cervical Cancer and Related Cervical Disease: A Review of the Cost-Effectiveness of Vaccination Against Oncogenic HPV Types". Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 16 (3): 217–30. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.3.217. PMID 20331326.

zur Hausen, Harald (2002). "Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application". Nature Reviews Cancer. 2 (5): 342–350. doi:10.1038/nrc798. ISSN 1474-1768. PMID 12044010.

Beachler, Daniel C.; Kreimer, Aimée R.; Schiffman, Mark; Herrero, Rolando; Wacholder, Sholom; Rodriguez, Ana Cecilia; Lowy, Douglas R.; Porras, Carolina; Schiller, John T. (January 2016). "Multisite HPV16/18 Vaccine Efficacy Against Cervical, Anal, and Oral HPV Infection". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 108 (1): djv302. doi:10.1093/jnci/djv302. ISSN 0027-8874. PMC 4862406. PMID 26467666.

Kreimer, Aimée R.; Herrero, Rolando; Sampson, Joshua N.; Porras, Carolina; Lowy, Douglas R.; Schiller, John T.; Schiffman, Mark; Rodriguez, Ana Cecilia; Chanock, Stephen (August 2018). "Evidence for single-dose protection by the bivalent HPV vaccine—Review of the Costa Rica HPV vaccine trial and future research studies". Vaccine. 36 (32): 4774–4782. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.078. PMC 6054558. PMID 29366703.

Menczer, J (February 2003). "The low incidence of cervical cancer in Jewish women: has the puzzle finally been solved?". The Israel Medical Association Journal : IMAJ. 5 (2): 120–3. PMID 12674663. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

Heins HC, Dennis EJ, Pratthomas HR (1958). "The possible role of smegma in carcinoma of the cervix". American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 76 (4): 726–33. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(58)90004-8. PMID 13583012.

Alexander ER (1973). "Possible Etiologies of Cancer of the Cervix Other Than Herpesvirus". Cancer Research. 33 (6): 1485–90. PMID 4352386.

Rosenblatt, Alberto; Guidi, Homero Gustavo de Campos (2009-08-06). Human Papillomavirus: A Practical Guide for Urologists. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783540709749.

Dürst M, Gissmann L, Ikenberg H, zur Hausen H (1983). "A papillomavirus DNA from a cervical carcinoma and its prevalence in cancer biopsy samples from different geographic regions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (12): 3812–5. Bibcode:1983PNAS...80.3812D. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.12.3812. PMC 394142. PMID 6304740..

Lowy DR, Schiller JT (2006). "Prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines". J. Clin. Invest. 116 (5): 1167–73. doi:10.1172/JCI28607. PMC 1451224. PMID 16670757.

McNeil C (April 2006). "Who invented the VLP cervical cancer vaccines?". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 98 (7): 433. doi:10.1093/jnci/djj144. PMID 16595773.

Cancer Institute NSW (2013). "Information about cervical screening for Aboriginal women". NSW Government. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013.

Mary-Anne Romano (17 October 2011). "Aboriginal cervical cancer rates parallel health inequity". Science Network Western Australia. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013.

Australian Cervical Cancer Foundation. "Vision and Mission". Australian Cervical Cancer Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013.

Australian Cervical Cancer Foundation. "Our People". Australian Cervical Cancer Foundation. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013.

Gillian Bradford (16 October 2006). "Janette Howard speaks on her battle with cervical cancer". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012.

Tiro JA, Meissner HI, Kobrin S, Chollette V (2007). "What do women in the U.S. know about human papillomavirus and cervical cancer?". Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 16 (2): 288–94. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0756. PMID 17267388.

Singh, Gopal K.; Miller, Barry A.; Hankey, Benjamin F.; Edwards, Brenda K. (2004-09-01). "Persistent area socioeconomic disparities in U.S. incidence of cervical cancer, mortality, stage, and survival, 1975–2000". Cancer. 101 (5): 1051–1057. doi:10.1002/cncr.20467. ISSN 1097-0142. PMID 15329915. |