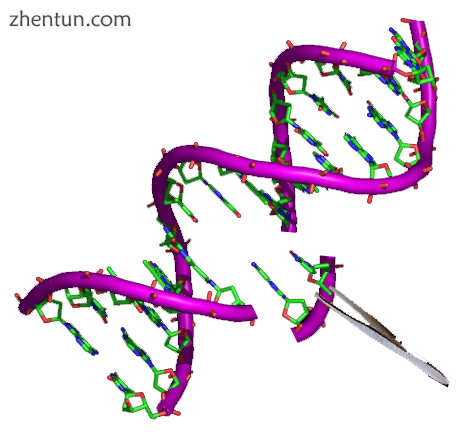

基因工程,也称为遗传修饰或遗传操作,是使用生物技术直接操纵生物体的基因。它是一组用于改变细胞遗传组成的技术,包括物种边界内和跨物种边界的基因转移,以产生改良的或新的生物。通过使用重组DNA方法分离和复制目的遗传物质或通过人工合成DNA获得新DNA。通常产生构建体并用于将该DNA插入宿主生物中。第一个重组DNA分子是由Paul Berg在1972年通过将来自猴病毒SV40的DNA与λ病毒组合而制备的。除插入基因外,该过程还可用于去除或“敲除”基因。新DNA可以随机插入,或靶向基因组的特定部分。

通过基因工程产生的生物体被认为是遗传修饰的(GM),并且所得实体是转基因生物(GMO)。第一个GMO是由Herbert Boyer和Stanley Cohen于1973年生成的细菌.Rudolf Jaenisch于1974年将外源DNA插入小鼠时创造了第一个转基因动物。第一家专注于基因工程的公司Genentech成立于1976年,开始生产人类蛋白质。基因工程人胰岛素于1978年生产,产生胰岛素的细菌于1982年商业化。转基因食品自1994年以来一直在销售,随着Flavr Savr番茄的释放。 Flavr Savr的设计具有更长的保质期,但大多数现有的转基因作物经过改良以增加对昆虫和除草剂的抗性。作为宠物设计的第一款GMO GloFish于2003年12月在美国销售。2016年,销售了用生长激素改良的鲑鱼。

基因工程已应用于许多领域,包括研究,医学,工业生物技术和农业。在研究中,转基因生物通过功能丧失,功能获得,追踪和表达实验来研究基因功能和表达。通过敲除对某些条件负责的基因,可以创建人类疾病的动物模型生物。除了产生激素,疫苗和其他药物外,基因工程还有可能通过基因治疗来治愈遗传性疾病。用于生产药物的相同技术也可以具有工业应用,例如生产用于洗衣洗涤剂,奶酪和其他产品的酶。

商业化转基因作物的兴起为许多不同国家的农民带来了经济利益,但也成为围绕该技术的大多数争议的根源。这种情况自早期使用以来一直存在;第一次田间试验被反转基因活动家摧毁。虽然科学界一致认为,目前可获得的转基因作物食品对人类健康的危害不大于传统食品,但转基因食品安全是批评者关注的主要问题。基因流动,对非目标生物的影响,对食物供应的控制和知识产权也被提出作为潜在问题。这些问题导致了一个始于1975年的监管框架的发展。它导致了一项国际条约,即卡塔赫纳生物安全议定书,于2000年通过。各个国家已经建立了自己的转基因生物监管体系,美国和欧洲之间出现最显着的差异。

IUPAC定义

基因工程:将新的遗传信息插入现有细胞以修改特定生物体以改变其特征的过程。注:改编自参考文献[1] [2]

目录

1 概述

2 历史

3 流程

3.1 基因分离和克隆

3.2 将DNA插入宿主基因组

4 应用

4.1 医学

4.2 研究

4.3 产业

4.4 农业

4.5 其他应用

5 调控

6 争议

7 在流行文化中

8 参考

概述

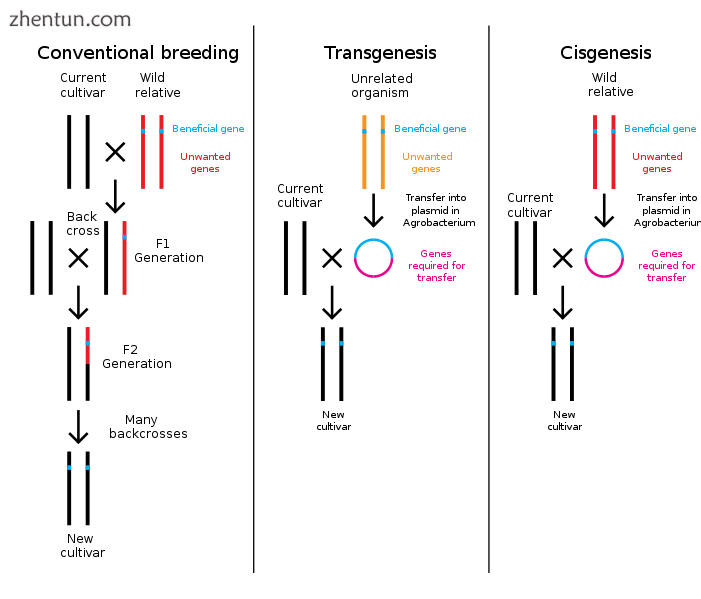

常规植物育种与转基因和顺式遗传修饰的比较

基因工程是通过去除或引入DNA来改变生物体遗传结构的过程。与传统的动物和植物育种不同,传统的动物和植物育种涉及多个杂交,然后选择具有所需表型的生物体,基因工程直接从一个生物体中获取基因并将其插入另一个生物体中。这种方法要快得多,可用于插入任何生物体(甚至来自不同结构域的基因)的任何基因,并防止其他不需要的基因被添加。[3]

基因工程可以通过用功能基因取代有缺陷的基因来潜在地修复人类的严重遗传疾病。[4]它是研究中的一个重要工具,可以研究特定基因的功能。[5]药物,疫苗和其他产品是从生产它们的生物体中收获的。[6]已经开发出通过提高产量,营养价值和对环境压力的耐受性来帮助粮食安全的作物。[7]

可以将DNA直接导入宿主生物体或导入细胞,然后与宿主融合或杂交。[8]这依赖于重组核酸技术形成可遗传的遗传物质的新组合,然后通过载体系统间接地或通过微注射,宏观注射或微囊化直接掺入该材料。[9]

基因工程通常不包括传统育种,体外受精,多倍体诱导,诱变和细胞融合技术,这些技术在此过程中不使用重组核酸或转基因生物。[8]然而,基因工程的一些广泛定义包括选择性育种。[9]克隆和干细胞研究,虽然不被认为是基因工程,[10]密切相关,基因工程可以在其中使用。[11]合成生物学是一门新兴学科,通过将人工合成材料引入生物体,使基因工程更进一步。[12]

通过基因工程改变的植物,动物或微生物被称为转基因生物或转基因生物。[13]如果将来自另一物种的遗传物质添加到宿主中,则所得生物称为转基因生物。如果使用来自同一物种的遗传物质或可与宿主天然繁殖的物种,则所得的生物称为顺式生物。[14]如果使用基因工程从目标生物体中去除遗传物质,则所得生物体被称为基因敲除生物体。[15]在欧洲,遗传修饰与基因工程同义,而在美国和加拿大,遗传修饰也可用于指更常规的育种方法。[16] [17] [18]

历史

主要文章:基因工程史

人类通过选择性育种或人工选择改变了物种的基因组数千年[19]:1 [20]:1与自然选择形成对比。最近,突变育种使用暴露于化学品或辐射以产生高频率的随机突变,用于选择性育种目的。基因工程作为人类在繁殖和突变之外直接操纵DNA,自20世纪70年代以来才存在。 “基因工程”一词最早是由杰克威廉姆森在他的科幻小说“龙之岛”中创造的,于1951年出版[21] - 一年之前,DNA在遗传中的作用得到了阿尔弗雷德·赫尔希和玛莎·蔡斯的证实,[22]两年前詹姆斯沃森和弗朗西斯克里克表明,DNA分子具有双螺旋结构 - 尽管直接遗传操作的一般概念是在Stanley G. Weinbaum 1936年的科幻故事Proteus Island中以初级形式进行探索的。[23] [24]

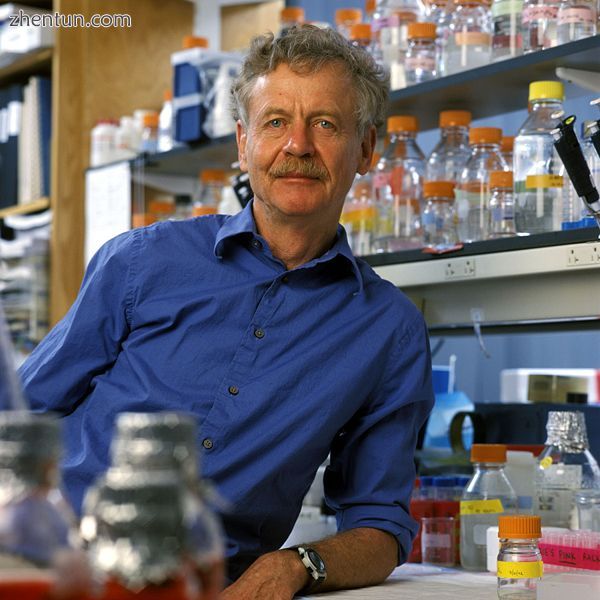

1974年,Rudolf Jaenisch创造了一种基因改造的老鼠,这是第一种转基因动物。

1972年,Paul Berg通过将猴病毒SV40的DNA与λ病毒的DNA结合,创造了第一个重组DNA分子。[25] 1973年,Herbert Boyer和Stanley Cohen通过将抗生素抗性基因插入大肠杆菌细菌质粒中创造了第一个转基因生物[26] [27]。一年后,Rudolf Jaenisch通过将外源DNA引入其胚胎中创造了一种转基因小鼠,使其成为世界上第一个转基因动物[28]。这些成就引起了科学界对基因工程潜在风险的关注,这些风险首先在这次会议的主要建议之一是政府应该对重组DNA研究进行监督,直到该技术被认为是安全的。[29] [30]

1976年,第一家基因工程公司Genentech由Herbert Boyer和Robert Swanson创立,一年后该公司在大肠杆菌中生产了一种人类蛋白质(生长抑素)。 Genentech于1978年宣布生产基因工程人胰岛素。[31] 1980年,美国最高法院在Diamond诉Chakrabarty一案中裁定,转基因生活可以获得专利。[32]细菌产生的胰岛素于1982年被美国食品和药物管理局(FDA)批准发布。[33]

1983年,一家生物技术公司Advanced Genetic Sc​​iences(AGS)申请美国政府授权用丁香假单胞菌的冰毒株进行田间试验以保护作物免受霜冻,但环保组织和抗议者推迟了四年的田间试验。法律挑战。[34] 1987年,当加利福尼亚州的草莓田和马铃薯田喷洒时,丁香假单胞菌的冰毒株成为第一个被释放到环境中的转基因生物(GMO)[36]。在测试发生的前一天晚上,两个测试区都受到了激进组织的攻击:“世界上第一个试验场地吸引了世界上第一个场地追踪者”。[35]

基因工程植物的第一次田间试验发生在1986年的法国和美国,烟草植物被设计成对除草剂具有抗性。[37]中华人民共和国是第一个将转基因植物商业化的国家,1992年引进了抗病毒烟草。[38] 1994年,Calgene获准批准商业发布第一种转基因食品Flavr Savr,这种番茄的保质期更长。[39] 1994年,欧盟批准烟草被设计为对除草剂溴苯腈具有抗性,使其成为欧洲第一个商业化的转基因作物。[40] 1995年,Bt Potato在获得FDA批准后获得了环境保护局的认可,成为第一个在美国批准的农药生产作物。[41] 2009年,11个转基因作物在25个国家进行商业化种植,其中面积最大的是美国,巴西,阿根廷,印度,加拿大,中国,巴拉圭和南非。[42]

2010年,J.Craig Venter研究所的科学家创造了第一个合成基因组,并将其插入空的细菌细胞中。 由此产生的细菌Mycoplasma laboratorium可以复制和生产蛋白质。[43] [44] 四年后,当开发出一种复制含有独特碱基对的质粒的细菌时,这又向前迈了一步,创造了第一个使用扩展遗传字母表的生物体。[45] [46] 2012年,Jennifer Doudna和Emmanuelle Charpentier合作开发了CRISPR / Cas9系统[47] [48],该技术可用于轻松,特异地改变几乎任何生物体的基因组。[49]

处理

主要文章:基因工程技术

聚合酶链反应是分子克隆中使用的有力工具

创建转基因生物是一个多步骤的过程。基因工程师必须首先选择他们希望插入生物体的基因。这是由最终生物体的目标所驱动的,并建立在早期研究的基础之上。可以进行遗传筛选以确定潜在的基因,然后进一步测试用于鉴定最佳候选基因。微阵列,转录组学和基因组测序的发展使得更容易找到合适的基因。[50]运气也发挥了作用;科学家注意到一种细菌在除草剂存在下蓬勃发展,发现了一种随心所欲的基因。[51]

基因分离和克隆

主要文章:分子克隆

下一步是分离候选基因。打开含有该基因的细胞,纯化DNA。[52]通过使用限制酶将基因切割成片段[53]或聚合酶链反应(PCR)以扩增基因片段。[54]然后可以通过凝胶电泳提取这些片段。如果选择的基因或供体生物体的基因组已经得到很好的研究,那么它可能已经可以从遗传文库中获得。如果DNA序列是已知的,但没有基因的拷贝可用,它也可以人工合成。[55]一旦分离,将基因连接到质粒中,然后将其插入细菌中。当细菌分裂时质粒被复制,确保基因的无限拷贝可用。[56]

在将基因插入目标生物体之前,必须将其与其他遗传元件组合。这些包括启动子和终止子区域,其起始和终止转录。添加了一种选择标记基因,在大多数情况下赋予抗生素抗性,因此研究人员可以轻松确定哪些细胞已经成功转化。该基因也可以在此阶段进行修饰,以获得更好的表达或有效性。这些操作使用重组DNA技术进行,例如限制性消化,连接和分子克隆。[57]

将DNA插入宿主基因组

主要文章:基因传递

基因枪使用生物射弹将DNA插入植物组织

有许多技术可用于将基因插入宿主基因组中。有些细菌可以自然地吸收外来DNA。这种能力可以通过应激(例如热或电击)在其他细菌中诱导,这增加了细胞膜对DNA的渗透性;摄取的DNA可以与基因组整合或作为染色体外DNA存在。通常使用显微注射将DNA插入动物细胞中,其中它可以通过细胞的核膜直接注射到细胞核中,或通过使用病毒载体注射。[58]

在植物中,DNA通常使用土壤杆菌介导的重组插入,[59]利用农杆菌T-DNA序列,允许遗传物质自然插入植物细胞。[60]其他方法包括生物射弹,其中金或钨的颗粒被DNA包覆,然后射入幼苗,[61]和电穿孔,其涉及使用电击使细胞膜可渗透质粒DNA。由于对细胞和DNA造成的损害,生物射弹和电穿孔的转化效率低于农杆菌转化和显微注射。[62]

由于只有一个细胞被遗传物质转化,所以必须从该单个细胞再生生物体。在植物中,这是通过使用组织培养来完成的。[63] [64]在动物中,有必要确保插入的DNA存在于胚胎干细胞中。[65]细菌由单个细胞组成并克隆繁殖,因此不需要再生。选择标记用于容易地区分转化细胞和未转化细胞。这些标记通常存在于转基因生物中,尽管已经开发了许多可以从成熟转基因植物中去除选择标记的策略[66]。

根癌农杆菌(A. tumefaciens)将自身附着在胡萝卜细胞上

使用PCR,Southern杂交和DNA测序进行进一步测试以确认生物体含有新基因。[67]这些测试还可以确认插入基因的染色体位置和拷贝数。基因的存在不能保证它将在靶组织中以适当的水平表达,因此也使用寻找和测量基因产物(RNA和蛋白质)的方法。这些包括Northern杂交,定量RT-PCR,Western印迹,免疫荧光,ELISA和表型分析。[68]

新的遗传物质可以随机插入宿主基因组中或靶向特定位置。基因靶向技术使用同源重组来对特定内源基因进行所需的改变。这往往在植物和动物中以相对低的频率发生,并且通常需要使用选择标记。通过基因组编辑可以大大提高基因打靶的频率。基因组编辑使用人工工程核酸酶,在基因组中的所需位置产生特异性双链断裂,并利用细胞的内源机制通过同源重组和非同源末端连接的自然过程修复诱导的断裂。有4个工程核酸酶家族:大范围核酸酶,[69] [70]锌指核酸酶,[71] [72]转录激活因子样效应核酸酶(TALENs),[73] [74]和Cas9-guideRNA系统(改编)来自CRISPR)。[75] [76] TALEN和CRISPR是最常用的两种,每种都有自己的优势。[77] TALEN具有更高的靶特异性,而CRISPR更容易设计和更有效。[77]除了增强基因靶向,工程化核酸酶还可用于在产生基因敲除的内源基因中引入突变。[78] [79]

应用

基因工程在医学,研究,工业和农业中具有应用,可用于广泛的植物,动物和微生物。细菌是第一个被遗传修饰的生物,可以插入含有新基因的质粒DNA,这些新基因编码处理食物和其他底物的药物或酶。[80] [81]植物已被改良以保护昆虫,抗除草剂,抗病毒,增强营养,对环境压力的耐受性和可食用疫苗的生产。[82]大多数商业化的转基因生物都是抗虫或耐除草剂的作物。[83]转基因动物已被用于研究,模型动物和农业或医药产品的生产。转基因动物包括基因被敲除的动物,对疾病的易感性增加,额外生长的激素以及在牛奶中表达蛋白质的能力。[84]

医学

基因工程在医学上有许多应用,包括药物的制造,模仿人类条件的模型动物的创造和基因治疗。基因工程最早的用途之一是在细菌中大规模生产人胰岛素。[31]该应用现已应用于人类生长激素,卵泡刺激激素(用于治疗不孕症),人白蛋白,单克隆抗体,抗血友病因子,疫苗和许多其他药物。[85] [86]小鼠杂交瘤,融合在一起产生单克隆抗体的细胞,已通过基因工程改造成人单克隆抗体。[87] 2017年,患者自身T细胞上的嵌合抗原受体的基因工程被美国FDA批准用于治疗癌症急性淋巴细胞白血病。正在开发的基因工程病毒仍可以提供免疫力,但缺乏感染性序列。[88]

基因工程也用于创建人类疾病的动物模型。转基因小鼠是最常见的基因工程动物模型。[89]它们已被用于研究和模拟癌症(oncomouse),肥胖,心脏病,糖尿病,关节炎,药物滥用,焦虑,衰老和帕金森病。[90]可以针对这些小鼠模型测试潜在的治愈方法。此外,还培育了经过基因改造的猪,目的是提高猪对人体器官移植的成功率。[91]

基因疗法是人类的基因工程,通常通过用有效基因替换缺陷基因。已经对几种疾病进行了体细胞基因治疗的临床研究,包括X连锁SCID,[92]慢性淋巴细胞白血病(CLL),[93] [94]和帕金森氏病[95]。 2012年,Alipogene一起成为第一个被批准用于临床的基因治疗药物。[96] [97] 2015年,一种病毒被用来将一个健康的基因插入患有罕见皮肤病,大疱性表皮松解症的男孩的皮肤细胞中,以便生长,然后将健康的皮肤移植到受男孩身体影响的80%的身体上疾病。[98]

种系基因治疗会导致任何可遗传的变化,这引起了科学界的关注。[99] [100] 2015年,CRISPR被用于编辑无活力人类胚胎的DNA,[101] [102]主要世界科学院的主要科学家呼吁暂停可遗传的人类基因组编辑。[103]还有人担心该技术不仅可用于治疗,还可用于增强,修改或改变人类的外表,适应性,智力,性格或行为。[104]治愈和增强之间的区别也很难确定。[105]在2018年11月,何建奎宣布他编辑了两个人类胚胎的基因组,试图禁用CCR5基因,该基因编码HIV用于进入细胞的受体。他说双胞胎女孩露露和娜娜几周前就出生了。他说,这些女孩仍然携带CCR5的功能性副本以及残疾的CCR5(镶嵌现象),并且仍然容易感染艾滋病毒。这项工作被广泛谴责为不道德,危险和过早。[106]

研究人员正在改变猪的基因组,以诱导人体器官的生长,用于移植。科学家正在创造“基因驱动”,改变蚊子的基因组,使其免疫疟疾,然后寻求将蚊子传播给蚊子,以期消灭这种疾病。[107]

研究

基因剔除鼠

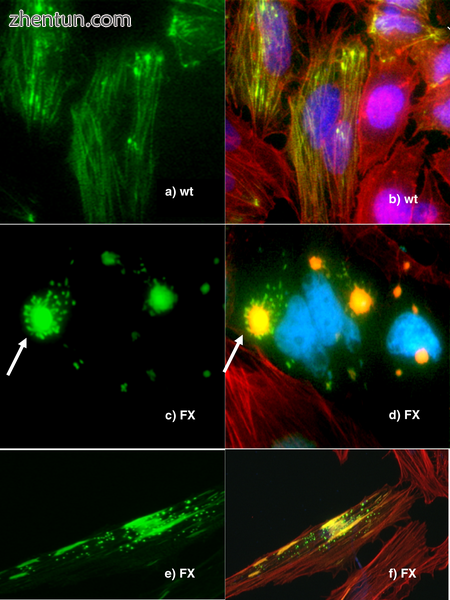

人体细胞,其中一些蛋白质与绿色荧光蛋白融合,以使它们可视化

基因工程是自然科学家的重要工具,转基因生物的创造是分析基因功能的最重要工具之一。[108]来自各种生物的基因和其他遗传信息可以插入细菌中进行储存和修饰,在此过程中产生转基因细菌。细菌便宜,易于生长,克隆,繁殖快,相对容易转化,几乎可以无限期地储存在-80°C。一旦基因被分离出来,它就可以储存在细菌内,为研究提供无限的供应。[109]生物体经过基因工程改造以发现某些基因的功能。这可能是对生物表型的影响,其中基因被表达或与其相互作用的其他基因。这些实验通常涉及功能丧失,功能获得,跟踪和表达。

功能丧失实验,例如在基因敲除实验中,其中生物被改造为缺乏一种或多种基因的活性。在简单的敲除中,所需基因的拷贝已被改变以使其无功能。胚胎干细胞包含改变的基因,取代已经存在的功能性拷贝。将这些干细胞注入胚泡中,胚泡植入代孕母亲体内。这允许实验者分析由该突变引起的缺陷,从而确定特定基因的作用。它在发育生物学中特别常用。[110]当通过在感兴趣区域的每个位置或甚至整个基因中的每个位置创建具有点突变的基因库来完成此操作时,这称为“扫描诱变”。最简单的方法,也就是第一个使用的方法是“丙氨酸扫描”,其中每个位置依次突变为非反应性氨基酸丙氨酸。[111]

功能实验的获得,淘汰赛的逻辑对应物。这些有时与敲除实验一起进行,以更精细地建立所需基因的功能。该过程与敲除工程中的过程大致相同,不同之处在于构建体旨在增加基因的功能,通常通过提供额外的基因拷贝或更频繁地诱导蛋白质的合成。功能的获得用于判断蛋白质是否足以用于功能,但并不总是意味着它是必需的,特别是在处理遗传或功能冗余时。[110]

跟踪实验,寻求获得有关所需蛋白质的定位和相互作用的信息。一种方法是用“融合”基因取代野生型基因,该基因是野生型基因与绿色荧光蛋白(GFP)等报告元素的并置,可以轻松实现产品的可视化遗传修饰。虽然这是一种有用的技术,但操作可以破坏基因的功能,产生次要效应并可能对实验结果提出质疑。目前正在开发更复杂的技术,可以跟踪蛋白质产品而不降低其功能,例如添加可作为单克隆抗体结合基序的小序列。[110]

表达研究旨在发现特定蛋白质的产生地点和时间。在这些实验中,编码蛋白质的DNA(称为基因启动子)之前的DNA序列被重新引入生物体,蛋白质编码区域被报告基因(如GFP或催化染料产生的酶)取代。 。因此,可以观察到产生特定蛋白质的时间和地点。通过改变启动子以发现哪些片段对于基因的正确表达至关重要并且实际上被转录因子蛋白结合,可以进一步进行表达研究。这个过程被称为推动者抨击。[112]

产业

生物体可以用编码有用蛋白质(如酶)的基因转化细胞,这样它们就会过表达所需的蛋白质。然后可以通过使用工业发酵在生物反应器设备中培养转化的生物体,然后纯化蛋白质来制造大量的蛋白质。有些基因在细菌中效果不佳,因此也可以使用酵母,昆虫细胞或哺乳动物细胞。[114]这些技术用于生产药物,如胰岛素,人体生长激素和疫苗,补充剂如色氨酸,帮助生产食品(奶酪制作中的凝乳酶)和燃料。[115]使用基因工程细菌的其他应用可能涉及使它们在自然循环之外执行任务,例如制造生物燃料,[116]清理漏油,碳和其他有毒废物[117]并检测饮用水中的砷。[118]某些转基因微生物也可用于生物矿化和生物修复,因为它们能够从环境中提取重金属并将其纳入更易于回收的化合物中。[119]

在材料科学中,转基因病毒已被用于研究实验室,作为组装更环保的锂离子电池的支架。[120] [121]通过在某些环境条件下表达荧光蛋白,细菌也被设计成用作传感器。[122]

农业

主要文章:转基因作物和转基因食品

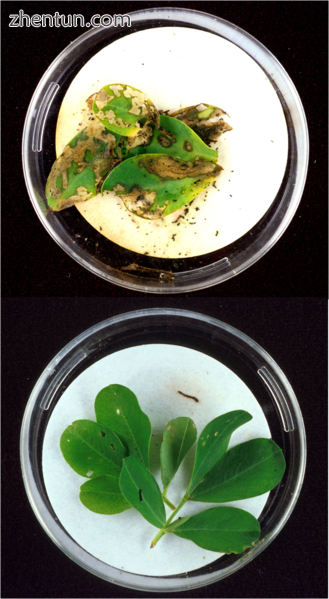

花生叶中存在的Bt毒素(底部图像)可以保护它免受较少的玉米螟幼虫造成的广泛破坏(上图)。[123]

基因工程最着名和最有争议的应用之一是创造和使用转基因作物或转基因牲畜来生产转基因食品。已经开发了作物以增加产量,增加对非生物胁迫的耐受性,改变食物的组成,或生产新产品。[124]

第一批商业上大规模释放的作物提供了对害虫的保护或对除草剂的耐受性。抗病毒和抗病毒作物也已经开发或正在开发中。[125] [126]这使作物的昆虫和杂草管理更容易,并可间接提高作物产量。[127] [128]转基因作物通过加速生长或使植物更加耐寒(通过提高盐,耐寒或耐旱性)直接提高产量,也正在开发中。[129] 2016年,鲑鱼已经用生长激素进行基因改造,以更快地达到正常成年体型。[130]

已开发出转基因生物,通过提高营养价值或提供更多工业上有用的品质或数量来改变农产品的质量。[129] Amflora马铃薯产生更加工业上有用的淀粉混合物。大豆和油菜经过基因改造以生产更健康的油。[131] [132]第一种商品化的转基因食品是一种延迟成熟的番茄,延长了其保质期。[133]

已经设计了植物和动物以生产它们通常不会制造的材料。药物使用作物和动物作为生物反应器来生产疫苗,药物中间体或药物本身;从收获物中纯化有用的产物,然后用于标准的药物生产过程。[134]奶牛和山羊经过精心设计,可以在牛奶中表达药物和其他蛋白质。2009年,FDA批准了一种用山羊奶生产的药物。[135] [136]

其他应用

基因工程在保护和自然区管理方面具有潜在的应用。已经提出通过病毒载体进行基因转移作为控制入侵物种以及从疾病中接种受威胁动物群的手段。[137]已提出转基因树木是一种赋予野生种群病原体抵抗力的方法。[138]随着气候变化和其他扰动导致生物体适应不良的风险增加,通过基因调整促进适应可能是减少灭绝风险的一种解决方案。[139]遗传工程在保护中的应用迄今为止主要是理论上的,尚未付诸实践。

基因工程也被用于创造微生物艺术。[140]一些细菌经过基因工程改造,可以制作黑白照片。[141]薰衣草色康乃馨,[142]蓝玫瑰,[143]和发光鱼[144] [145]等新奇物品也是通过基因工程生产的。

规定

主要文章:基因工程的规定

基因工程的监管涉及政府评估和管理与转基因生物的开发和释放相关的风险的方法。监管框架的制定始于1975年,位于加利福尼亚州的Asilomar。[146] Asilomar会议建议了一套关于重组技术使用的自愿准则。[29]随着技术的进步,美国在科学技术办公室设立了一个委员会,[147]该委员会将转基因食品的监管批准转交给美国农业部,FDA和EPA。[148] “卡塔赫纳生物安全议定书”是一项管理转基因生物转移,处理和使用的国际条约,[149]于2000年1月29日通过。[150] 157个国家是“议定书”的成员,许多国家将其作为自己条例的参考点。[151]

转基因食品的法律和监管地位因国家而异,一些国家禁止或限制它们,另一些国家允许它们具有不同程度的监管。[152] [153] [154] [155]一些国家允许经授权进口转基因食品,但要么不允许进口转基因食品(俄罗斯,挪威,以色列),要么即使没有生产转基因产品(日本,韩国)也要有种植。大多数不允许转基因植物种植的国家都允许进行研究。[156]美国和欧洲之间出现了一些最显着的差异。美国的政策侧重于产品(而不是过程),只关注可验证的科学风险,并使用实质等同的概念。[157]相比之下,欧盟可能是世界上最严格的转基因生物法规。[158]所有转基因生物以及辐照食品都被视为“新食品”,并受到欧洲食品安全局的广泛,逐案,基于科学的食品评估。授权标准分为四大类:“安全”,“选择自由”,“标签”和“可追溯性”。[159]其他培育转基因生物的国家的监管水平介于欧洲和美国之间。

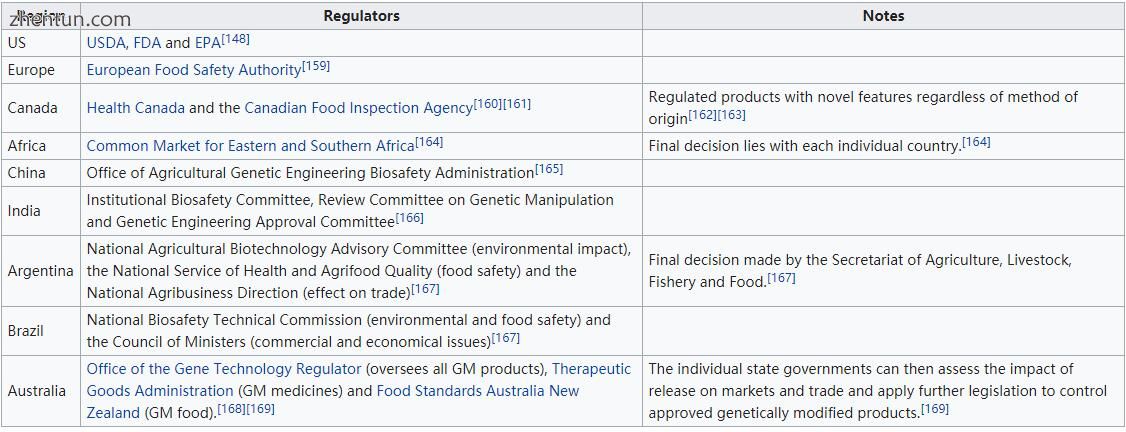

按地理区域划分的监管机构

与监管机构有关的一个关键问题是转基因产品是否应贴上标签。欧盟委员会表示,需要强制性标签和可追溯性,以便做出明智的选择,避免潜在的虚假广告[170],并在发现对健康或环境的不利影响时促进产品的撤销。[171]美国医学协会[172]和美国科学促进会[173]表示,即使自愿标签缺乏科学证据也不会产生误导,并会误导消费者。 64个国家/地区需要在市场上标注转基因产品。[174]标签可以是强制性的,直到GM内容级别(在各国之间不同)或自愿的。在加拿大和美国,转基因食品的标签是自愿的,[175]而在欧洲,所有含有超过0.9%经批准的转基因生物的食品(包括加工食品)或饲料必须贴上标签。[158]

争议

主要文章:转基因食品争议

批评者反对基因工程的使用有几个原因,包括道德,生态和经济问题。其中许多问题涉及转基因作物以及由它们生产的食物是否安全以及它们对环境的影响。这些争议导致诉讼,国际贸易纠纷和抗议活动,以及某些国家对商业产品的限制性监管。[176]

科学家们“扮演上帝”的指责和其他宗教问题从一开始就归功于这项技术。[177]提出的其他道德问题包括生命专利,[178]知识产权的使用,[179]产品标签的水平,[180] [181]对食品供应的控制[182]以及监管的客观性过程。[183]虽然已经提出了疑问,但[184]经济上大多数研究都发现转基因作物的种植对农民有益。[185] [186] [187]

转基因作物和相容植物之间的基因流动,以及选择性除草剂的使用增加,都会增加“超级杂草”发展的风险。[188]其他环境问题涉及对非目标生物的潜在影响,包括土壤微生物,[189]以及次生和抗性害虫的增加。[190] [191]转基因作物的许多环境影响可能需要很多年才能理解,而且在传统农业实践中也很明显。[189] [192]随着转基因鱼类的商业化,人们担心如果它们逃脱会对环境造成什么后果。[193]

关于转基因食品的安全性有三个主要问题:它们是否会引起过敏反应;基因是否可以从食物转移到人体细胞中;以及未批准供人食用的基因是否可以与其他作物交叉。[194]科学共识[195] [196] [197] [198]目前可获得的转基因作物食品对人类健康的危害不大于传统食品,[199] [200] [201] [202] [203] ]但每种转基因食品需要在引入前逐案检测。[204] [205] [206]尽管如此,公众成员比科学家更不可能认为转基因食品是安全的。[207] [208] [209] [210]

在流行文化中

主要文章:小说中的遗传学§基因工程

许多科幻小说中的基因工程特征。[211]弗兰克赫伯特的小说“白瘟疫”描述了故意使用基因工程来制造一种特别杀害妇女的病原体。[211]另一个赫伯特的创作,沙丘系列小说,使用基因工程来创造强大但被鄙视的Tleilaxu。[212]像The Island和Blade Runner这样的电影带来了工程化的生物来对抗创造它的人或者克隆它的人。很少有电影向观众介绍基因工程,除了1978年的巴西男孩和1993年的侏罗纪公园,两者都利用了一个教训,一个示范和一个科学电影剪辑。[213] [214]基因工程方法在电影中表现不佳;为威康信托基金会撰写的迈克尔克拉克称,在第六天的电影中,基因工程和生物技术的描写“严重扭曲”[214]。在克拉克看来,生物技术通常“被赋予了奇妙但视觉上引人注目的形式”,而科学要么被降级为背景,要么被虚构化以适合年轻观众。[214]

另见

Biological engineering

参考:

"Terms and Acronyms". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency online. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

Vert M, Doi Y, Hellwich KH, Hess M, Hodge P, Kubisa P, Rinaudo M, Schué F (2012). "Terminology for biorelated polymers and applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 84 (2): 377–410. doi:10.1351/PAC-REC-10-12-04.

"How does GM differ from conventional plant breeding?". royalsociety.org. Retrieved 2017-11-14.

Erwin E, Gendin S, Kleiman L (2015-12-22). Ethical Issues in Scientific Research: An Anthology. Routledge. p. 338. ISBN 978-1134817740.

Alexander DR (May 2003). "Uses and abuses of genetic engineering". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 79 (931): 249–51. doi:10.1136/pmj.79.931.249. PMC 1742694. PMID 12782769.

Nielsen J (2013-07-01). "Production of biopharmaceutical proteins by yeast: advances through metabolic engineering". Bioengineered. 4 (4): 207–11. doi:10.4161/bioe.22856. PMC 3728191. PMID 23147168.

Qaim M, Kouser S (2013-06-05). "Genetically modified crops and food security". PLOS One. 8 (6): e64879. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...864879Q. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064879. PMC 3674000. PMID 23755155.

The European Parliament and the council of the European Union (12 March 2001). "Directive on the release of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) Directive 2001/18/EC ANNEX I A". Official Journal of the European Communities.

Staff Economic Impacts of Genetically Modified Crops on the Agri-Food Sector; p. 42 Glossary – Term and Definitions Archived 14 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. The European Commission Directorate-General for Agriculture, "Genetic engineering: The manipulation of an organism's genetic endowment by introducing or eliminating specific genes through modern molecular biology techniques. A broad definition of genetic engineering also includes selective breeding and other means of artificial selection.", Retrieved 5 November 2012

Van Eenennaam A. "Is Livestock Cloning Another Form of Genetic Engineering?" (PDF). agbiotech. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011.

Suter DM, Dubois-Dauphin M, Krause KH (July 2006). "Genetic engineering of embryonic stem cells" (PDF). Swiss Medical Weekly. 136 (27–28): 413–5. PMID 16897894. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2011.

Andrianantoandro E, Basu S, Karig DK, Weiss R (16 May 2006). "Synthetic biology: new engineering rules for an emerging discipline". Molecular Systems Biology. 2 (2006.0028): 2006.0028. doi:10.1038/msb4100073. PMC 1681505. PMID 16738572.

"What is genetic modification (GM)?". CSIRO.

Jacobsen E, Schouten HJ (2008). "Cisgenesis, a New Tool for Traditional Plant Breeding, Should be Exempted from the Regulation on Genetically Modified Organisms in a Step by Step Approach". Potato Research. 51: 75–88. doi:10.1007/s11540-008-9097-y.

Capecchi MR (October 2001). "Generating mice with targeted mutations". Nature Medicine. 7 (10): 1086–90. doi:10.1038/nm1001-1086. PMID 11590420.

Staff Biotechnology – Glossary of Agricultural Biotechnology Terms Archived 30 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine. United States Department of Agriculture, "Genetic modification: The production of heritable improvements in plants or animals for specific uses, via either genetic engineering or other more traditional methods. Some countries other than the United States use this term to refer specifically to genetic engineering.", Retrieved 5 November 2012

Maryanski JH (19 October 1999). "Genetically Engineered Foods". Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition at the Food and Drug Administration.

Staff (28 November 2005) Health Canada – The Regulation of Genetically Modified Food Glossary definition of Genetically Modified: "An organism, such as a plant, animal or bacterium, is considered genetically modified if its genetic material has been altered through any method, including conventional breeding. A 'GMO' is a genetically modified organism.", Retrieved 5 November 2012

Root C (2007). Domestication. Greenwood Publishing Groups.

Zohary D, Hopf M, Weiss E (2012). Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The origin and spread of plants in the old world. Oxford University Press.

Stableford BM (2004). Historical dictionary of science fiction literature. p. 133. ISBN 978-0810849389.

Hershey AD, Chase M (May 1952). "Independent functions of viral protein and nucleic acid in growth of bacteriophage". The Journal of General Physiology. 36 (1): 39–56. doi:10.1085/jgp.36.1.39. PMC 2147348. PMID 12981234.

"Genetic Engineering". Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. 2 April 2015.

Shiv Kant Prasad, Ajay Dash (2008). Modern Concepts in Nanotechnology, Volume 5. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 978-8183562966.

Jackson DA, Symons RH, Berg P (October 1972). "Biochemical method for inserting new genetic information into DNA of Simian Virus 40: circular SV40 DNA molecules containing lambda phage genes and the galactose operon of Escherichia coli". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 69 (10): 2904–9. Bibcode:1972PNAS...69.2904J. doi:10.1073/pnas.69.10.2904. PMC 389671. PMID 4342968.

Arnold P (2009). "History of Genetics: Genetic Engineering Timeline".

Gutschi S, Hermann W, Stenzl W, Tscheliessnigg KH (1 May 1973). "[Displacement of electrodes in pacemaker patients (author's transl)]". Zentralblatt Fur Chirurgie. 104 (2): 100–4. Bibcode:1973PNAS...70.1293C. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.5.1293. PMC 433482.

Jaenisch R, Mintz B (April 1974). "Simian virus 40 DNA sequences in DNA of healthy adult mice derived from preimplantation blastocysts injected with viral DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 71 (4): 1250–4. PMC 388203. PMID 4364530.

Berg P, Baltimore D, Brenner S, Roblin RO, Singer MF (June 1975). "Summary statement of the Asilomar conference on recombinant DNA molecules". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 72 (6): 1981–4. Bibcode:1975PNAS...72.1981B. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.6.1981. PMC 432675. PMID 806076.

"NIH Guidelines for research involving recombinant DNA molecules". Office of Biotechnology Activities. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012.

Goeddel DV, Kleid DG, Bolivar F, Heyneker HL, Yansura DG, Crea R, Hirose T, Kraszewski A, Itakura K, Riggs AD (January 1979). "Expression in Escherichia coli of chemically synthesized genes for human insulin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 76 (1): 106–10. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76..106G. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.1.106. PMC 382885. PMID 85300.

US Supreme Court Cases from Justia & Oyez (16 June 1980). "Diamond V Chakrabarty". 447 (303). Supreme.justia.com. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

"Artificial Genes". TIME. 15 November 1982. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

Bratspies R (2007). "Some Thoughts on the American Approach to Regulating Genetically Modified Organisms". Kansas Journal of Law & Public Policy. 16 (3): 101–31. SSRN 1017832.

BBC News 14 June 2002 GM crops: A bitter harvest?

Thomas H. Maugh II for the Los Angeles Times. 9 June 1987. Altered Bacterium Does Its Job : Frost Failed to Damage Sprayed Test Crop, Company Says

James C (1996). "Global Review of the Field Testing and Commercialization of Transgenic Plants: 1986 to 1995" (PDF). The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

James C (1997). "Global Status of Transgenic Crops in 1997" (PDF). ISAAA Briefs No. 5.: 31.

Bruening G, Lyons JM (2000). "The case of the FLAVR SAVR tomato". California Agriculture. 54 (4): 6–7. doi:10.3733/ca.v054n04p6.

MacKenzie D (18 June 1994). "Transgenic tobacco is European first". New Scientist.

Genetically Altered Potato Ok'd For Crops Lawrence Journal-World – 6 May 1995

Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2009 ISAAA Brief 41-2009, 23 February 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2010

Pennisi E (May 2010). "Genomics. Synthetic genome brings new life to bacterium". Science. 328 (5981): 958–9. doi:10.1126/science.328.5981.958. PMID 20488994.

Gibson DG, Glass JI, Lartigue C, Noskov VN, Chuang RY, Algire MA, et al. (July 2010). "Creation of a bacterial cell controlled by a chemically synthesized genome". Science. 329 (5987): 52–6. Bibcode:2010Sci...329...52G. doi:10.1126/science.1190719. PMID 20488990.

Malyshev DA, Dhami K, Lavergne T, Chen T, Dai N, Foster JM, Corrêa IR, Romesberg FE (May 2014). "A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet". Nature. 509 (7500): 385–8. Bibcode:2014Natur.509..385M. doi:10.1038/nature13314. PMC 4058825. PMID 24805238.

Thyer R, Ellefson J (May 2014). "Synthetic biology: New letters for life's alphabet". Nature. 509 (7500): 291–2. Bibcode:2014Natur.509..291T. doi:10.1038/nature13335. PMID 24805244.

Pollack A (2015-05-11). "Jennifer Doudna, a Pioneer Who Helped Simplify Genome Editing". The New York Times. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, Hauer M, Doudna JA, Charpentier E (August 2012). "A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity". Science. 337 (6096): 816–21. Bibcode:2012Sci...337..816J. doi:10.1126/science.1225829. PMID 22745249.

Ledford H (March 2016). "CRISPR: gene editing is just the beginning". Nature. 531 (7593): 156–9. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..156L. doi:10.1038/531156a. PMID 26961639.

Koh H, Kwon S, Thomson M (2015-08-26). Current Technologies in Plant Molecular Breeding: A Guide Book of Plant Molecular Breeding for Researchers. Springer. p. 242. ISBN 978-9401799966.

"How to Make a GMO". Science in the News. 2015-08-09. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

Nicholl, Desmond S.T. (2008-05-29). An Introduction to Genetic Engineering. Cambridge University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-1139471787.

Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, et al. (2002). "8". Isolating, Cloning, and Sequencing DNA (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science.

Kaufman RI, Nixon BT (July 1996). "Use of PCR to isolate genes encoding sigma54-dependent activators from diverse bacteria". Journal of Bacteriology. 178 (13): 3967–70. doi:10.1128/jb.178.13.3967-3970.1996. PMC 232662. PMID 8682806.

Liang J, Luo Y, Zhao H (2011). "Synthetic biology: putting synthesis into biology". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Systems Biology and Medicine. 3 (1): 7–20. doi:10.1002/wsbm.104. PMC 3057768. PMID 21064036.

"5. The Process of Genetic Modification". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

Berg P, Mertz JE (January 2010). "Personal reflections on the origins and emergence of recombinant DNA technology". Genetics. 184 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1534/genetics.109.112144. PMC 2815933. PMID 20061565.

Chen I, Dubnau D (March 2004). "DNA uptake during bacterial transformation". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 2 (3): 241–9. doi:10.1038/nrmicro844. PMID 15083159.

National Research Council (US) Committee on Identifying and Assessing Unintended Effects of Genetically Engineered Foods on Human Health (2004-01-01). Methods and Mechanisms for Genetic Manipulation of Plants, Animals, and Microorganisms. National Academies Press (US).

Gelvin SB (March 2003). "Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation: the biology behind the "gene-jockeying" tool". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 67 (1): 16–37, table of contents. doi:10.1128/MMBR.67.1.16-37.2003. PMC 150518. PMID 12626681.

Head G, Hull RH, Tzotzos GT (2009). Genetically Modified Plants: Assessing Safety and Managing Risk. London: Academic Pr. p. 244. ISBN 0123741068.

Darbani B, Farajnia S, Toorchi M, Zakerbostanabad S, Noeparvar S, Stewart CN (2010). "DNA-Delivery Methods to Produce Transgenic Plants". Science Alert.

Tuomela M, Stanescu I, Krohn K (October 2005). "Validation overview of bio-analytical methods". Gene Therapy. 12 Suppl 1 (S1): S131–8. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3302627. PMID 16231045.

Narayanaswamy, S. (1994). Plant Cell and Tissue Culture. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. pp. vi. ISBN 978-0074602775.

National Research Council (US) Committee on Identifying and Assessing Unintended Effects of Genetically Engineered Foods on Human Health (2004). Methods and Mechanisms for Genetic Manipulation of Plants, Animals, and Microorganisms. National Academies Press (US).

Hohn B, Levy AA, Puchta H (April 2001). "Elimination of selection markers from transgenic plants". Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 12 (2): 139–43. doi:10.1016/S0958-1669(00)00188-9. PMID 11287227.

Setlow JK (2002-10-31). Genetic Engineering: Principles and Methods. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 109. ISBN 978-0306472800.

Deepak S, Kottapalli K, Rakwal R, Oros G, Rangappa K, Iwahashi H, Masuo Y, Agrawal G (June 2007). "Real-Time PCR: Revolutionizing Detection and Expression Analysis of Genes". Current Genomics. 8 (4): 234–51. doi:10.2174/138920207781386960. PMC 2430684. PMID 18645596.

Grizot S, Smith J, Daboussi F, Prieto J, Redondo P, Merino N, Villate M, Thomas S, Lemaire L, Montoya G, Blanco FJ, Paques F, Duchateau P (September 2009). "Efficient targeting of a SCID gene by an engineered single-chain homing endonuclease". Nucleic Acids Research. 37 (16): 5405–19. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp548. PMC 2760784. PMID 19584299.

Gao H, Smith J, Yang M, Jones S, Djukanovic V, Nicholson MG, West A, Bidney D, Falco SC, Jantz D, Lyznik LA (January 2010). "Heritable targeted mutagenesis in maize using a designed endonuclease". The Plant Journal. 61 (1): 176–87. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04041.x. PMID 19811621.

Townsend JA, Wright DA, Winfrey RJ, Fu F, Maeder ML, Joung JK, Voytas DF (May 2009). "High-frequency modification of plant genes using engineered zinc-finger nucleases". Nature. 459 (7245): 442–5. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..442T. doi:10.1038/nature07845. PMC 2743854. PMID 19404258.

Shukla VK, Doyon Y, Miller JC, DeKelver RC, Moehle EA, Worden SE, Mitchell JC, Arnold NL, Gopalan S, Meng X, Choi VM, Rock JM, Wu YY, Katibah GE, Zhifang G, McCaskill D, Simpson MA, Blakeslee B, Greenwalt SA, Butler HJ, Hinkley SJ, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD (May 2009). "Precise genome modification in the crop species Zea mays using zinc-finger nucleases". Nature. 459 (7245): 437–41. Bibcode:2009Natur.459..437S. doi:10.1038/nature07992. PMID 19404259.

Christian M, Cermak T, Doyle EL, Schmidt C, Zhang F, Hummel A, Bogdanove AJ, Voytas DF (October 2010). "Targeting DNA double-strand breaks with TAL effector nucleases". Genetics. 186 (2): 757–61. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.120717. PMC 2942870. PMID 20660643.

Li T, Huang S, Jiang WZ, Wright D, Spalding MH, Weeks DP, Yang B (January 2011). "TAL nucleases (TALNs): hybrid proteins composed of TAL effectors and FokI DNA-cleavage domain". Nucleic Acids Research. 39 (1): 359–72. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq704. PMC 3017587. PMID 20699274.

Esvelt KM, Wang HH (2013). "Genome-scale engineering for systems and synthetic biology". Molecular Systems Biology. 9: 641. doi:10.1038/msb.2012.66. PMC 3564264. PMID 23340847.

Tan WS, Carlson DF, Walton MW, Fahrenkrug SC, Hackett PB (2012). "Precision editing of large animal genomes". Advances in Genetics. Advances in Genetics. 80: 37–97. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-404742-6.00002-8. ISBN 978-0124047426. PMC 3683964. PMID 23084873.

Malzahn A, Lowder L, Qi Y (2017-04-24). "Plant genome editing with TALEN and CRISPR". Cell & Bioscience. 7: 21. doi:10.1186/s13578-017-0148-4. PMC 5404292. PMID 28451378.

Ekker SC (2008). "Zinc finger-based knockout punches for zebrafish genes". Zebrafish. 5 (2): 121–3. doi:10.1089/zeb.2008.9988. PMC 2849655. PMID 18554175.

Geurts AM, Cost GJ, Freyvert Y, Zeitler B, Miller JC, Choi VM, Jenkins SS, Wood A, Cui X, Meng X, Vincent A, Lam S, Michalkiewicz M, Schilling R, Foeckler J, Kalloway S, Weiler H, Ménoret S, Anegon I, Davis GD, Zhang L, Rebar EJ, Gregory PD, Urnov FD, Jacob HJ, Buelow R (July 2009). "Knockout rats via embryo microinjection of zinc-finger nucleases". Science. 325 (5939): 433. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..433G. doi:10.1126/science.1172447. PMC 2831805. PMID 19628861.

"Genetic Modification of Bacteria". Annenberg Foundation.

Panesar, Pamit et al (2010) "Enzymes in Food Processing: Fundamentals and Potential Applications", Chapter 10, I K International Publishing House, ISBN 978-9380026336

"GM traits list". International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications.

"ISAAA Brief 43-2011: Executive Summary". International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications.

Connor S (2 November 2007). "The mouse that shook the world". The Independent.

Avise JC (2004). The hope, hype & reality of genetic engineering: remarkable stories from agriculture, industry, medicine, and the environment. Oxford University Press US. p. 22. ISBN 978-0195169508.

"Engineering algae to make complex anti-cancer 'designer' drug". PhysOrg. 10 December 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

Roque AC, Lowe CR, Taipa MA (2004). "Antibodies and genetically engineered related molecules: production and purification". Biotechnology Progress. 20 (3): 639–54. doi:10.1021/bp030070k. PMID 15176864.

Rodriguez LL, Grubman MJ (November 2009). "Foot and mouth disease virus vaccines". Vaccine. 27 Suppl 4: D90–4. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.08.039. PMID 19837296.

"Background: Cloned and Genetically Modified Animals". Center for Genetics and Society. 14 April 2005.

"Knockout Mice". Nation Human Genome Research Institute. 2009.

"GM pigs best bet for organ transplant". Medical News Today. 21 September 2003.

Fischer A, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Cavazzana-Calvo M (June 2010). "20 years of gene therapy for SCID". Nature Immunology. 11 (6): 457–60. doi:10.1038/ni0610-457. PMID 20485269.

Ledford H (2011). "Cell therapy fights leukaemia". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.472.

Brentjens RJ, Davila ML, Riviere I, Park J, Wang X, Cowell LG, et al. (March 2013). "CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia". Science Translational Medicine. 5 (177): 177ra38. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3005930. PMC 3742551. PMID 23515080.

LeWitt PA, Rezai AR, Leehey MA, Ojemann SG, Flaherty AW, Eskandar EN, et al. (April 2011). "AAV2-GAD gene therapy for advanced Parkinson's disease: a double-blind, sham-surgery controlled, randomised trial". The Lancet. Neurology. 10 (4): 309–19. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70039-4. PMID 21419704.

Gallagher, James. (2 November 2012) BBC News – Gene therapy: Glybera approved by European Commission. Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved on 15 December 2012.

Richards S. "Gene Therapy Arrives in Europe". The Scientist. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

"Genetically Altered Skin Saves A Boy Dying Of A Rare Disease". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-11-15.

"1990 The Declaration of Inuyama". 5 August 2001. Archived from the original on 5 August 2001.

Smith KR, Chan S, Harris J. Human germline genetic modification: scientific and bioethical perspectives. Arch Med Res. 2012 Oct;43(7):491-513. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.09.003. PMID 23072719

Kolata G (23 April 2015). "Chinese Scientists Edit Genes of Human Embryos, Raising Concerns". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

Liang P, Xu Y, Zhang X, Ding C, Huang R, Zhang Z, Lv J, Xie X, Chen Y, Li Y, Sun Y, Bai Y, Songyang Z, Ma W, Zhou C, Huang J (May 2015). "CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes". Protein & Cell. 6 (5): 363–372. doi:10.1007/s13238-015-0153-5. PMC 4417674. PMID 25894090.

Wade N (3 December 2015). "Scientists Place Moratorium on Edits to Human Genome That Could Be Inherited". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

Bergeson ER (1997). "The Ethics of Gene Therapy".

Hanna KE. "Genetic Enhancement". National Human Genome Research Institute.

Begley S (28 November 2018). "Amid uproar, Chinese scientist defends creating gene-edited babies – STAT". STAT.

Harmon A (2015-11-26). "Open Season Is Seen in Gene Editing of Animals". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-09-27.

Praitis V, Maduro MF (2011). "Transgenesis in C. elegans". Methods in Cell Biology. 106: 161–85. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-544172-8.00006-2. PMID 22118277.

"Rediscovering Biology – Online Textbook: Unit 13 Genetically Modified Organisms". www.learner.org. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P (2002). "Studying Gene Expression and Function".

Park SJ, Cochran JR (2009-09-25). Protein Engineering and Design. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1420076592.

Kurnaz IA (2015-05-08). Techniques in Genetic Engineering. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1482260908.

"Applications of Genetic Engineering". Microbiologyprocedure. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

"Biotech: What are transgenic organisms?". Easyscience. 2002. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

Savage N (1 August 2007). "Making Gasoline from Bacteria: A biotech startup wants to coax fuels from engineered microbes". Technology Review. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

Summers R (24 April 2013). "Bacteria churn out first ever petrol-like biofuel". New Scientist. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

"Applications of Some Genetically Engineered Bacteria". Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

Sanderson K (24 February 2012). "New Portable Kit Detects Arsenic In Wells". Chemical and Engineering News. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

Reece JB, Urry LA, Cain ML, Wasserman SA, Minorsky PV, Jackson RB (2011). Campbell Biology Ninth Edition. San Francisco: Pearson Benjamin Cummings. p. 421. ISBN 0321558235.

"New virus-built battery could power cars, electronic devices". Web.mit.edu. 2 April 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

"Hidden Ingredient In New, Greener Battery: A Virus". Npr.org. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

"Researchers Synchronize Blinking 'Genetic Clocks' – Genetically Engineered Bacteria That Keep Track of Time". ScienceDaily. 24 January 2010.

Suszkiw J (November 1999). "Tifton, Georgia: A Peanut Pest Showdown". Agricultural Research magazine. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

Magaña-Gómez JA, de la Barca AM (January 2009). "Risk assessment of genetically modified crops for nutrition and health". Nutrition Reviews. 67 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00130.x. PMID 19146501.

Islam A (2008). "Fungus Resistant Transgenic Plants: Strategies, Progress and Lessons Learnt". Plant Tissue Culture and Biotechnology. 16 (2): 117–38. doi:10.3329/ptcb.v16i2.1113.

"Disease resistant crops". GMO Compass. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010.

Demont M, Tollens E (2004). "First impact of biotechnology in the EU: Bt maize adoption in Spain". Annals of Applied Biology. 145 (2): 197–207. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.2004.tb00376.x.

Chivian E, Bernstein A (2008). Sustaining Life. Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0195175097.

Whitman DB (2000). "Genetically Modified Foods: Harmful or Helpful?".

Pollack A (19 November 2015). "Genetically Engineered Salmon Approved for Consumption". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

Rapeseed (canola) has been genetically engineered to modify its oil content with a gene encoding a "12:0 thioesterase" (TE) enzyme from the California bay plant (Umbellularia californica) to increase medium length fatty acids, see: Geo-pie.cornell.edu Archived 5 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

Bomgardner MM (2012). "Replacing Trans Fat: New crops from Dow Chemical and DuPont target food makers looking for stable, heart-healthy oils". Chemical and Engineering News. 90 (11): 30–32.

Kramer MG, Redenbaugh K (1994-01-01). "Commercialization of a tomato with an antisense polygalacturonase gene: The FLAVR SAVR™ tomato story". Euphytica. 79 (3): 293–97. doi:10.1007/BF00022530. ISSN 0014-2336.

Marvier M (2008). "Pharmaceutical crops in California, benefits and risks. A review". Agronomy for Sustainable Development. 28 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1051/agro:2007050.

"FDA Approves First Human Biologic Produced by GE Animals". US Food and Drug Administration.

Rebêlo P (15 July 2004). "GM cow milk 'could provide treatment for blood disease'". SciDev.

Angulo E, Cooke B (December 2002). "First synthesize new viruses then regulate their release? The case of the wild rabbit". Molecular Ecology. 11 (12): 2703–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01635.x. PMID 12453252.

Adams JM, Piovesan G, Strauss S, Brown S (2 August 2002). "The Case for Genetic Engineering of Native and Landscape Trees against Introduced Pests and Diseases". Conservation Biology. 16: 874–79. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00523.x.

Thomas MA, Roemer GW, Donlan CJ, Dickson BG, Matocq M, Malaney J (September 2013). "Ecology: Gene tweaking for conservation". Nature. 501 (7468): 485–6. doi:10.1038/501485a. PMID 24073449.

Pasko JM (2007-03-04). "Bio-artists bridge gap between arts, sciences: Use of living organisms is attracting attention and controversy". msnbc.

Jackson J (6 December 2005). "Genetically Modified Bacteria Produce Living Photographs". National Geographic News.

Phys.Org website. 4 April 2005 "Plant gene replacement results in the world's only blue rose".

Katsumoto Y, Fukuchi-Mizutani M, Fukui Y, Brugliera F, Holton TA, Karan M, Nakamura N, Yonekura-Sakakibara K, Togami J, Pigeaire A, Tao GQ, Nehra NS, Lu CY, Dyson BK, Tsuda S, Ashikari T, Kusumi T, Mason JG, Tanaka Y (November 2007). "Engineering of the rose flavonoid biosynthetic pathway successfully generated blue-hued flowers accumulating delphinidin". Plant & Cell Physiology. 48 (11): 1589–600. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcm131. PMID 17925311.

Published PCT Application WO2000049150 "Chimeric Gene Constructs for Generation of Fluorescent Transgenic Ornamental Fish." National University of Singapore [1]

Stewart CN (April 2006). "Go with the glow: fluorescent proteins to light transgenic organisms" (PDF). Trends in Biotechnology. 24 (4): 155–62. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.02.002. PMID 16488034.

Berg P, Baltimore D, Boyer HW, Cohen SN, Davis RW, Hogness DS, Nathans D, Roblin R, Watson JD, Weissman S, Zinder ND (July 1974). "Letter: Potential biohazards of recombinant DNA molecules" (PDF). Science. 185 (4148): 303. Bibcode:1974Sci...185..303B. doi:10.1126/science.185.4148.303. PMC 388511. PMID 4600381.

McHughen A, Smyth S (January 2008). "US regulatory system for genetically modified [genetically modified organism (GMO), rDNA or transgenic] crop cultivars". Plant Biotechnology Journal. 6 (1): 2–12. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00300.x. PMID 17956539.

U.S. Office of Science and Technology Policy (June 1986). "Coordinated framework for regulation of biotechnology; announcement of policy; notice for public comment" (PDF). Federal Register. 51 (123): 23302–50. PMID 11655807. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011.

Redick, T.P. (2007). "The Cartagena Protocol on biosafety: Precautionary priority in biotech crop approvals and containment of commodities shipments, 2007". Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy. 18: 51–116.

"About the Protocol". The Biosafety Clearing-House (BCH).

"AgBioForum 13(3): Implications of Import Regulations and Information Requirements under the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety for GM Commodities in Kenya".

"Restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms". Library of Congress. 9 June 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

Bashshur R (February 2013). "FDA and Regulation of GMOs". American Bar Association. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

Sifferlin A (3 October 2015). "Over Half of E.U. Countries Are Opting Out of GMOs". Time.

Lynch D, Vogel D (5 April 2001). "The Regulation of GMOs in Europe and the United States: A Case-Study of Contemporary European Regulatory Politics". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

"Restrictions on Genetically Modified Organisms - Law Library of Congress". 22 January 2017.

Emily Marden, Risk and Regulation: U.S. Regulatory Policy on Genetically Modified Food and Agriculture, 44 B.C.L. Rev. 733 (2003)[2]

Davison J (2010). "GM plants: Science, politics and EC regulations". Plant Science. 178 (2): 94–98. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2009.12.005.

GMO Compass: The European Regulatory System. Archived 14 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

Government of Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency. "Information for the general public". www.inspection.gc.ca.

Forsberg, Cecil W. (23 April 2013). "Genetically Modified Foods". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

Evans, Brent and Lupescu, Mihai (15 July 2012) Canada – Agricultural Biotechnology Annual – 2012 GAIN (Global Agricultural Information Network) report CA12029, United States Department of Agriculture, Foreifn Agricultural Service, Retrieved 5 November 2012

McHugen A (14 September 2000). "Chapter 1: Hors-d'oeuvres and entrees/What is genetic modification? What are GMOs?". Pandora's Picnic Basket. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198506744.

Transgenic harvest Editorial, Nature 467, pp. 633–34, 7 October 2010, doi:10.1038/467633b. Retrieved 9 November 2010

"AgBioForum 5(4): Agricultural Biotechnology Development and Policy in China".

"TNAU Agritech Portal: Bio Technology".

"BASF presentation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2011.

Agriculture – Department of Primary Industries Archived 29 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

"Welcome to the Office of the Gene Technology Regulator Website". Office of the Gene Technology Regulator. Retrieved 25 March 2011.

"Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 On Genetically Modified Food And Feed" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2014. The labeling should include objective information to the effect that a food or feed consists of, contains or is produced from GMOs. Clear labeling, irrespective of the detectability of DNA or protein resulting from the genetic modification in the final product, meets the demands expressed in numerous surveys by a large majority of consumers, facilitates informed choice and precludes potential misleading of consumers as regards methods of manufacture or production.

"Regulation (EC) No 1830/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 concerning the traceability and labeling of genetically modified organisms and the traceability of food and feed products produced from genetically modified organisms and amending Directive 2001/18/EC". Official Journal L 268. The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union. 2003. pp. 24–28. (3) Traceability requirements for GMOs should facilitate both the withdrawal of products where unforeseen adverse effects on human health, animal health or the environment, including ecosystems, are established, and the targeting of monitoring to examine potential effects on, in particular, the environment. Traceability should also facilitate the implementation of risk management measures in accordance with the precautionary principle. (4) Traceability requirements for food and feed produced from GMOs should be established to facilitate accurate labeling of such products.

"Report 2 of the Council on Science and Public Health: Labeling of Bioengineered Foods" (PDF). American Medical Association. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2012.

American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), Board of Directors (2012). Statement by the AAAS Board of Directors On Labeling of Genetically Modified Foods, and associated Press release: Legally Mandating GM Food Labels Could Mislead and Falsely Alarm Consumers

Hallenbeck T (2014-04-27). "How GMO labeling came to pass in Vermont". Burlington Free Press. Retrieved 2014-05-28.

"The Regulation of Genetically Modified Foods".

Sheldon IM (2002-03-01). "Regulation of biotechnology: will we ever 'freely' trade GMOs?". European Review of Agricultural Economics. 29 (1): 155–76. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.596.7670. doi:10.1093/erae/29.1.155. ISSN 0165-1587.

Dabrock P (December 2009). "Playing God? Synthetic biology as a theological and ethical challenge". Systems and Synthetic Biology. 3 (1–4): 47–54. doi:10.1007/s11693-009-9028-5. PMC 2759421. PMID 19816799.

Brown C (October 2000). "Patenting life: genetically altered mice an invention, court declares". Cmaj. 163 (7): 867–8. PMC 80518. PMID 11033718.

Zhou W (2015-08-10). "The Patent Landscape of Genetically Modified Organisms". Science in the News. Retrieved 2017-05-05.

Puckett L (2016-04-20). "Why The New GMO Food-Labeling Law Is So Controversial". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2017-05-05.

Miller H (2016-04-12). "GMO food labels are meaningless". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 2017-05-05.

Savage S. "Who Controls The Food Supply?". Forbes. Retrieved 2017-05-05.

Knight AJ (2016-04-14). Science, Risk, and Policy. Routledge. p. 156. ISBN 978-1317280811.

Hakim D (2016-10-29). "Doubts About the Promised Bounty of Genetically Modified Crops". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-05-05.

Areal FJ, Riesgo L, Rodríguez-Cerezo E (2013-02-01). "Economic and agronomic impact of commercialized GM crops: a meta-analysis". The Journal of Agricultural Science. 151 (1): 7–33. doi:10.1017/S0021859612000111.

Finger R, El Benni N, Kaphengst T, Evans C, Herbert S, Lehmann B, Morse S, Stupak N (2011-05-10). "A Meta Analysis on Farm-Level Costs and Benefits of GM Crops". Sustainability. 3 (5): 743–62. doi:10.3390/su3050743.

Klümper W, Qaim M (2014-11-03). "A meta-analysis of the impacts of genetically modified crops". PLOS One. 9 (11): e111629. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k1629K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111629. PMC 4218791. PMID 25365303.

Qiu J (2013). "Genetically modified crops pass benefits to weeds". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.13517.

"GMOs and the environment". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

Dively GP, Venugopal PD, Finkenbinder C (2016-12-30). "Field-Evolved Resistance in Corn Earworm to Cry Proteins Expressed by Transgenic Sweet Corn". PLOS One. 11 (12): e0169115. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1169115D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169115. PMC 5201267. PMID 28036388.

Qiu, Jane (2010-05-13). "GM crop use makes minor pests major problem". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2010.242.

Gilbert N (May 2013). "Case studies: A hard look at GM crops". Nature. 497 (7447): 24–6. Bibcode:2013Natur.497...24G. doi:10.1038/497024a. PMID 23636378.

"Are GMO Fish Safe for the Environment? | Accumulating Glitches | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

"Q&A: genetically modified food". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2017-05-07.

Nicolia A, Manzo A, Veronesi F, Rosellini D (March 2014). "An overview of the last 10 years of genetically engineered crop safety research". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 34 (1): 77–88. doi:10.3109/07388551.2013.823595. PMID 24041244. We have reviewed the scientific literature on GE crop safety for the last 10 years that catches the scientific consensus matured since GE plants became widely cultivated worldwide, and we can conclude that the scientific research conducted so far has not detected any significant hazard directly connected with the use of GM crops.

The literature about Biodiversity and the GE food/feed consumption has sometimes resulted in animated debate regarding the suitability of the experimental designs, the choice of the statistical methods or the public accessibility of data. Such debate, even if positive and part of the natural process of review by the scientific community, has frequently been distorted by the media and often used politically and inappropriately in anti-GE crops campaigns.

"State of Food and Agriculture 2003–2004. Agricultural Biotechnology: Meeting the Needs of the Poor. Health and environmental impacts of transgenic crops". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 8 February 2016. Currently available transgenic crops and foods derived from them have been judged safe to eat and the methods used to test their safety have been deemed appropriate. These conclusions represent the consensus of the scientific evidence surveyed by the ICSU (2003) and they are consistent with the views of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2002). These foods have been assessed for increased risks to human health by several national regulatory authorities (inter alia, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, China, the United Kingdom and the United States) using their national food safety procedures (ICSU). To date no verifiable untoward toxic or nutritionally deleterious effects resulting from the consumption of foods derived from genetically modified crops have been discovered anywhere in the world (GM Science Review Panel). Many millions of people have consumed foods derived from GM plants – mainly maize, soybean and oilseed rape – without any observed adverse effects (ICSU).

Ronald P (May 2011). "Plant genetics, sustainable agriculture and global food security". Genetics. 188 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1534/genetics.111.128553. PMC 3120150. PMID 21546547. There is broad scientific consensus that genetically engineered crops currently on the market are safe to eat. After 14 years of cultivation and a cumulative total of 2 billion acres planted, no adverse health or environmental effects have resulted from commercialization of genetically engineered crops (Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources, Committee on Environmental Impacts Associated with Commercialization of Transgenic Plants, National Research Council and Division on Earth and Life Studies 2002). Both the U.S. National Research Council and the Joint Research Centre (the European Union's scientific and technical research laboratory and an integral part of the European Commission) have concluded that there is a comprehensive body of knowledge that adequately addresses the food safety issue of genetically engineered crops (Committee on Identifying and Assessing Unintended Effects of Genetically Engineered Foods on Human Health and National Research Council 2004; European Commission Joint Research Centre 2008). These and other recent reports conclude that the processes of genetic engineering and conventional breeding are no different in terms of unintended consequences to human health and the environment (European Commission Directorate-General for Research and Innovation 2010).

But see also: Domingo JL, Giné Bordonaba J (May 2011). "A literature review on the safety assessment of genetically modified plants". Environment International. 37 (4): 734–42. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2011.01.003. PMID 21296423. In spite of this, the number of studies specifically focused on safety assessment of GM plants is still limited. However, it is important to remark that for the first time, a certain equilibrium in the number of research groups suggesting, on the basis of their studies, that a number of varieties of GM products (mainly maize and soybeans) are as safe and nutritious as the respective conventional non-GM plant, and those raising still serious concerns, was observed. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that most of the studies demonstrating that GM foods are as nutritional and safe as those obtained by conventional breeding, have been performed by biotechnology companies or associates, which are also responsible of commercializing these GM plants. Anyhow, this represents a notable advance in comparison with the lack of studies published in recent years in scientific journals by those companies. Krimsky S (2015). "An Illusory Consensus behind GMO Health Assessment" (PDF). Science, Technology, & Human Values. 40: 1–32. doi:10.1177/0162243915598381. I began this article with the testimonials from respected scientists that there is literally no scientific controversy over the health effects of GMOs. My investigation into the scientific literature tells another story. And contrast:

Panchin AY, Tuzhikov AI (March 2017). "Published GMO studies find no evidence of harm when corrected for multiple comparisons". Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 37 (2): 213–217. doi:10.3109/07388551.2015.1130684. PMID 26767435. Here, we show that a number of articles some of which have strongly and negatively influenced the public opinion on GM crops and even provoked political actions, such as GMO embargo, share common flaws in the statistical evaluation of the data. Having accounted for these flaws, we conclude that the data presented in these articles does not provide any substantial evidence of GMO harm.

The presented articles suggesting possible harm of GMOs received high public attention. However, despite their claims, they actually weaken the evidence for the harm and lack of substantial equivalency of studied GMOs. We emphasize that with over 1783 published articles on GMOs over the last 10 years it is expected that some of them should have reported undesired differences between GMOs and conventional crops even if no such differences exist in reality. and

Yang YT, Chen B (April 2016). "Governing GMOs in the USA: science, law and public health". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 96 (6): 1851–5. doi:10.1002/jsfa.7523. PMID 26536836. It is therefore not surprising that efforts to require labeling and to ban GMOs have been a growing political issue in the USA (citing Domingo and Bordonaba, 2011).

Overall, a broad scientific consensus holds that currently marketed GM food poses no greater risk than conventional food... Major national and international science and medical associations have stated that no adverse human health effects related to GMO food have been reported or substantiated in peer-reviewed literature to date.

Despite various concerns, today, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the World Health Organization, and many independent international science organizations agree that GMOs are just as safe as other foods. Compared with conventional breeding techniques, genetic engineering is far more precise and, in most cases, less likely to create an unexpected outcome.

"Statement by the AAAS Board of Directors On Labeling of Genetically Modified Foods" (PDF). American Association for the Advancement of Science. 20 October 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2016. The EU, for example, has invested more than |