肝细胞癌(HCC)是成人中最常见的原发性肝癌,也是肝硬化患者最常见的死亡原因。

它发生在慢性肝炎的环境中,并且与慢性病毒性肝炎感染(乙型或丙型肝炎)或接触毒素(如酒精或黄曲霉毒素)最密切相关。某些疾病,例如血色素沉着病和α1-抗胰蛋白酶缺乏症,显着增加了发生HCC的风险。代谢综合症和NASH也日益被认为是HCC的危险因素。

与任何癌症一样,HCC的治疗和预后取决于肿瘤组织学,大小,癌症扩散的程度以及整体健康状况。

绝大多数HCC发生在亚洲和撒哈拉以南非洲,这些国家是乙型肝炎流行的国家,许多是从出生就感染的。由于丙型肝炎病毒感染的增加,在美国和其他发展中国家,HCC的发病率正在增加。由于未知原因,它在男性中比女性更普遍。

丙型肝炎阳性患者的肝细胞癌。尸检标本。

内容

1 体征和症状

2 危险因素

2.1 糖尿病

3 发病机理

4 诊断

4.1 筛选

4.2 高危人群

4.3 成像

4.4 病理学

4.5 分期

5 预防

6 治疗

6.1 手术切除

6.2 肝移植

6.3 消融

6.4 基于动脉导管的治疗

6.5 全身

6.6 其他

7 预后

8 流行病学

8.1 非洲和亚洲

8.2 北美和西欧

9 研究

9.1 临床前

9.2 临床

10 参考文献

体征和症状

大多数HCC病例发生在已经有慢性肝病症状和体征的人中。在癌症检测时,它们可能表现为症状加重或没有症状。 HCC可能直接伴有黄色皮肤,由于腹腔积液引起的腹部肿胀,因凝血异常而容易瘀伤,食欲不振,无意识的体重减轻,腹痛,恶心,呕吐或感到疲倦。

风险因素

肝癌主要发生在肝硬化患者中,因此危险因素通常包括导致可能导致肝硬化的慢性肝脏疾病的因素。尽管如此,某些风险因素与HCC的相关性远高于其他风险因素。例如,虽然估计大量饮酒会引起60%至70%的肝硬化,但绝大多数HCC发生在归因于病毒性肝炎的肝硬化中(尽管可能有重叠)。公认的危险因素包括:

慢性病毒性肝炎(全球估计原因为80%)

慢性乙型肝炎(约50%)

慢性丙型肝炎(约25%)

毒素:

酗酒:最常见的肝硬化原因

黄曲霉毒素

铁超载状态(血色素沉着症)

新陈代谢:

非酒精性脂肪性肝炎:肝硬化进展高达20%

2型糖尿病(可能是由肥胖引起的)

先天性疾病:

α1-抗胰蛋白酶缺乏症

威尔逊氏病(有争议;尽管有些理论认为风险增加,但案例研究很少,并且提出了与威尔逊氏病实际上可以提供保护的情况相反的说法)

血友病虽然在统计学上与较高的HCC风险相关,但这是由于与一生中反复输血有关的慢性病毒性肝炎同时感染。

这些风险因素的重要性在全球范围内各不相同。在中国东南部等乙型肝炎流行地区,这是主要原因。在美国等受到乙型肝炎疫苗很大程度上保护的人群中,肝癌最常与肝硬化的原因相关,例如慢性丙型肝炎,肥胖症和酗酒。

某些良性肝肿瘤,例如肝细胞腺瘤,有时可能与恶性肝癌并存。与良性腺瘤相关的恶性肿瘤的真正发病率的证据有限;但是,肝腺瘤的大小被认为与恶性肿瘤的风险相对应,因此可以通过手术切除较大的肿瘤。某些腺瘤亚型,特别是那些具有β-catenin激活突变的腺瘤,尤其与肝癌的风险增加有关。

儿童和青少年不太可能患有慢性肝病,但是如果他们患有先天性肝病,则这一事实会增加患上HCC的机会。具体而言,患有胆道闭锁,小儿胆汁淤积,糖原贮积病和其他肝硬化性肝病的儿童易患儿童肝癌。

受罕见的肝细胞纤维状变体折磨的年轻人可能没有典型的危险因素,即肝硬化和肝炎。

糖尿病

2型糖尿病患者发生肝细胞癌的风险更大(从非糖尿病风险的2.5到7.1倍),具体取决于糖尿病的持续时间和治疗方案。造成这种风险增加的一个可能原因是循环胰岛素浓度升高,使得胰岛素控制不佳或提高胰岛素输出量的糖尿病患者(均导致较高的循环胰岛素浓度)表现出的肝细胞癌风险要比糖尿病患者高。降低循环胰岛素浓度。在这一点上,一些严格控制胰岛素(通过阻止胰岛素升高)的糖尿病患者显示出足够低的风险水平,无法与普通人群区分开。因此,这种现象并非孤立于2型糖尿病,因为在其他情况下(例如,代谢综合征)(特别是当存在非酒精性脂肪肝疾病或NAFLD的证据时)也发现胰岛素调节不良,并且这里又存在更大风险的证据。虽然有人声称合成代谢类固醇滥用者的风险更高(理论上是由于胰岛素和IGF恶化所致),但唯一可以证实的证据是合成代谢类固醇使用者更容易患有肝细胞腺瘤(HCC的良性形式)转变为更危险的肝细胞癌。

发病

另请参阅:致癌作用

当影响细胞机制的表观遗传学改变和突变导致细胞以更高的速率复制和/或导致细胞避免凋亡时,就会发生肝细胞癌。

特别是,乙型肝炎和/或丙型肝炎的慢性感染可通过反复引起人体自身的免疫系统攻击肝细胞来帮助肝细胞癌的发展,其中一些被病毒感染,另一些仅仅是旁观者。活化的免疫系统炎症细胞释放自由基,例如活性氧和一氧化氮活性,这些自由基继而可能导致DNA损伤并导致致癌基因突变。活性氧也可在DNA修复位点引起表观遗传改变。

虽然这种持续不断的损坏然后进行修复的循环会导致修复过程中的错误,进而导致致癌,但这一假设目前更适用于丙型肝炎。慢性丙型肝炎会导致肝癌进入肝硬化阶段。然而,在慢性乙型肝炎中,病毒基因组整合到感染细胞中可以直接诱导非肝硬化肝发展为肝癌。或者,重复消耗大量乙醇会产生相似的效果。来自某些曲霉属真菌的毒素黄曲霉毒素是致癌物,可通过在肝脏中积累来辅助肝细胞癌的致癌作用。在中国和西非等地区,黄曲霉毒素和乙型肝炎的高发病率综合起来导致这些地区的肝细胞癌发病率相对较高。其他病毒性肝素(例如甲型肝炎)没有可能成为慢性感染,因此与HCC无关。

诊断

肝癌的诊断方法随着医学影像学的发展而发展。对无症状患者和有肝病症状的患者的评估都包括血液测试和影像学评估。尽管历史上需要对肿瘤进行活检以证实诊断,但影像学检查(尤其是MRI)可能是结论性的,足以消除组织病理学证实。

筛选

HCC仍然与高死亡率相关,部分与通常在疾病晚期的初步诊断有关。与其他癌症一样,如果在疾病过程中更早开始治疗,结果将显着改善。因为绝大多数HCC发生在患有某些慢性肝脏疾病的人中,尤其是患有肝硬化的人,所以在这一人群中通常提倡进行肝筛查。随着其临床影响的证据变得可用,特定的筛查指南会随着时间不断发展。在美国,最常观察到的指南是美国肝病研究协会发布的指南,该指南建议每6个月用超声筛查患有肝硬化的人,无论是否测量血液中肿瘤标志物甲胎蛋白的水平(法新社)。 AFP水平升高与活动性HCC疾病相关,尽管不一致。在> 20的水平下,灵敏度为41-65%,特异性为80-94%。但是,> 200的水平,灵敏度为31,特异性为99%。

在超声检查中,HCC常常表现为小的低回声病变,边缘定义不清,内部回声粗糙,不规则。肿瘤生长时,有时会出现异质性,纤维化,脂肪变化和钙化。这种异质性看起来类似于肝硬化和周围的肝实质。一项系统评价发现,与作为参考标准的移出或切除肝脏的病理检查相比,敏感性为60%(95%CI 44–76%),特异性为97%(95%CI 95–98%)。随着AFP相关性,灵敏度增加到79%。

关于最有效的筛查方案仍存在争议。例如,尽管一些数据支持降低了与乙型肝炎感染者筛查相关的死亡率,但AASLD指出。 “在慢性丙型肝炎或脂肪肝病继发的西方肝硬化人群中,没有用于筛查的随机试验,因此围绕监测是否确实导致该肝硬化患者的死亡率降低存在争议。”

高风险人士

对于存在较高HCC怀疑的人,例如具有症状或血液检查异常(即α-甲胎蛋白和des-γ羧化凝血酶原水平)的人,评估需要通过CT或MRI扫描对肝脏成像。 最佳情况下,这些扫描是在肝灌注的多个阶段以静脉内对比进行的,以提高放射科医师对任何肝脏病变的检测和准确分类的能力。 由于HCC肿瘤的特征性血流模式,任何检测到的肝病灶的特定灌注模式都可以最终检测出HCC肿瘤。 备选地,扫描可以检测到不确定的病变,并且可以通过获得病变的物理样本来进行进一步的评估。

影像学

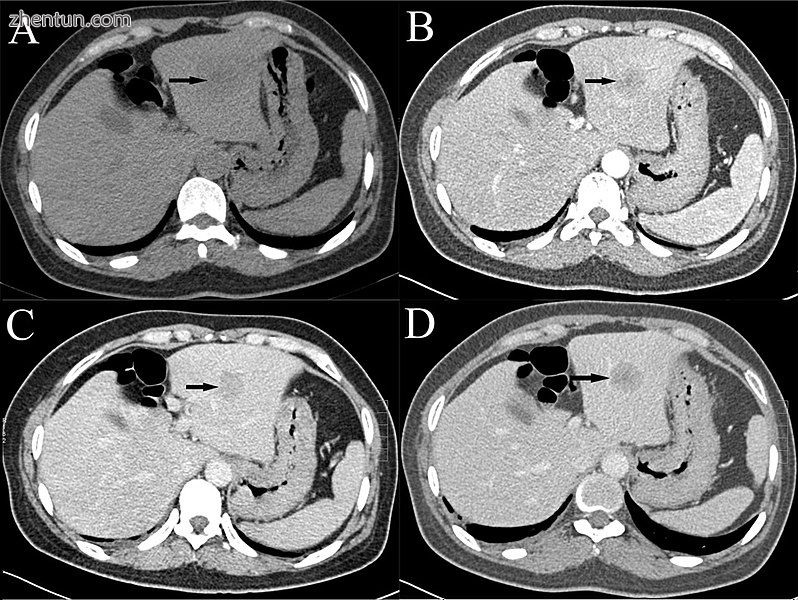

肝细胞癌的三期对比CT。

超声,CT扫描和MRI可用于评估肝的HCC。在CT和MRI上,HCC可以具有三种不同的生长方式:

单个大肿瘤

多发性肿瘤

肿瘤定义不清,具有浸润性生长模式

对CT诊断的系统评价发现,与以移出或切除的肝脏作为参考标准进行病理检查相比,其敏感性为68%(95%CI 55–80%),特异性为93%(95%CI 89–96%) 。对于三相螺旋CT,敏感性为90%或更高,但尸检研究尚未证实这些数据。

但是,MRI的优势在于无需电离辐射即可提供肝脏的高分辨率图像。 HCC在T2加权图像上显示为高强度模式,在T1加权图像上显示为低强度模式。 MRI的优势在于,与超声和CT相比,对于难以区分HCC和再生结节的肝硬化患者,MRI具有更高的敏感性和特异性。一项系统的审查发现,与作为参考标准的移出或切除肝脏的病理检查相比,敏感性为81%(95%CI 70-91%),特异性为85%(95%CI 77-93%)。如果将contrast对比增强和扩散加权成像相结合,则灵敏度会进一步提高。

MRI比CT更加灵敏和特异。

肝脏图像报告和数据系统(LI-RADS)是用于报告在CT和MRI上检测到的肝脏病变的分类系统。放射科医生使用此标准化系统报告可疑病变并提供估计的恶性可能性。按照对癌症的关注程度,类别从LI-RADS(LR)1到5。如果满足某些影像学标准,则无需进行活检即可确定HCC的诊断。

病理

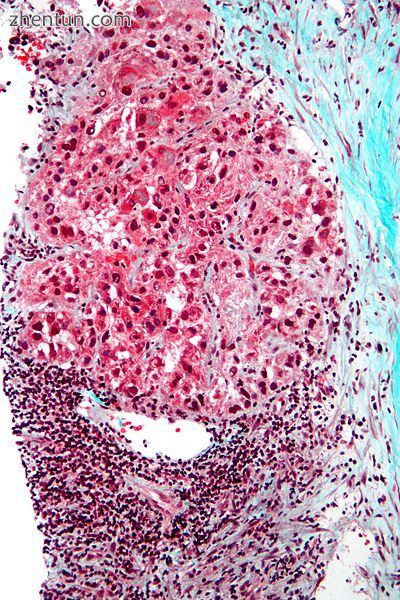

肝细胞癌的显微照片。肝活检。三色染色。

从宏观上看,肝癌表现为结节性或浸润性肿瘤。结节型可能是单发的(大块)或多发的(当发展为肝硬化并发症时)。肿瘤结节为圆形至卵圆形,灰色或绿色(如果肿瘤产生胆汁),边界清楚,但未包封。弥散型界限不清,浸润门静脉或肝静脉(很少)。

在显微镜下,肝细胞癌的四种结构和细胞学类型(模式)为:纤维状层状,假腺性(腺样体),多形性(巨细胞)和透明细胞。在分化良好的形式中,肿瘤细胞类似于肝细胞,形成小梁,索和巢,并且在细胞质中可能含有胆汁色素。分化较差的形式是,恶性上皮细胞具有歧义性,多形性,间变性和巨细胞。由于血管形成不良,肿瘤间质少,中心坏死。还描述了第五种形式-淋巴上皮瘤样肝细胞癌。

分期

BCLC分期系统

由于肝硬化的影响,肿瘤的分期和肝功能影响着肝癌的预后。

HCC有许多分期分类;但是,由于癌的独特性,使其充分涵盖了所有影响HCC分类的特征,因此分类系统应考虑肿瘤的大小和数量,是否存在血管浸润和肝外扩散,肝功能(血清胆红素水平和白蛋白,腹水和门脉高压的存在)以及患者的总体健康状况(由ECOG分类和症状的存在定义)。

在所有可用的分期分类系统中,巴塞罗那临床肝癌分期分类涵盖了以上所有特征。 此分期分类可用于选择要治疗的人员。

最常见的转移部位是肺,腹部淋巴结和骨骼。

预防

由于乙肝和丙肝是肝细胞癌的一些主要原因,因此预防感染是预防肝癌的关键。 因此,儿童时期接种乙型肝炎疫苗可能会降低将来患肝癌的风险。 对于肝硬化患者,应避免饮酒。 此外,筛查血色素沉着病可能对某些患者有益。 目前尚不清楚筛查患有慢性肝病的患者是否可改善结局。

治疗

肝细胞癌的治疗因疾病的阶段,患者耐受手术的可能性以及肝移植的可用性而异:

治愈意图:对于有限的疾病,当癌症局限于肝脏内的一个或多个区域时,手术切除恶性细胞可能是治愈性的。这可以通过切除肝脏的受影响部分(部分肝切除术)或在某些情况下通过整个器官的原位肝移植来实现。

“桥接”意图:对于有资格进行潜在肝移植的有限疾病,该人可以在等待供体器官可用的同时对某些或全部已知肿瘤进行靶向治疗。

“降级”意向:针对中度晚期疾病,该疾病尚未扩散到肝脏以外,但过于晚期而无法进行治疗。为了减小活动性肿瘤的大小或数量,可以通过靶向疗法来治疗该人,目的是在这种治疗后再次有资格进行肝移植。

姑息治疗意向:对于更晚期的疾病,包括癌症扩散到肝脏外或可能不耐受手术的人中,旨在减轻疾病症状并延长生存期的治疗。

局部区域疗法(也称为肝定向疗法)是指以肝内HCC为靶标的几种微创治疗技术中的任何一种。这些程序是手术的替代方法,可以与其他策略(例如以后的肝移植)结合使用。通常,这些治疗程序由介入放射科医生或外科医生与肿瘤内科医生共同进行。局部治疗可以指经皮治疗(例如冷冻消融)或基于动脉导管的治疗(化学栓塞或放射栓塞)。

手术切除

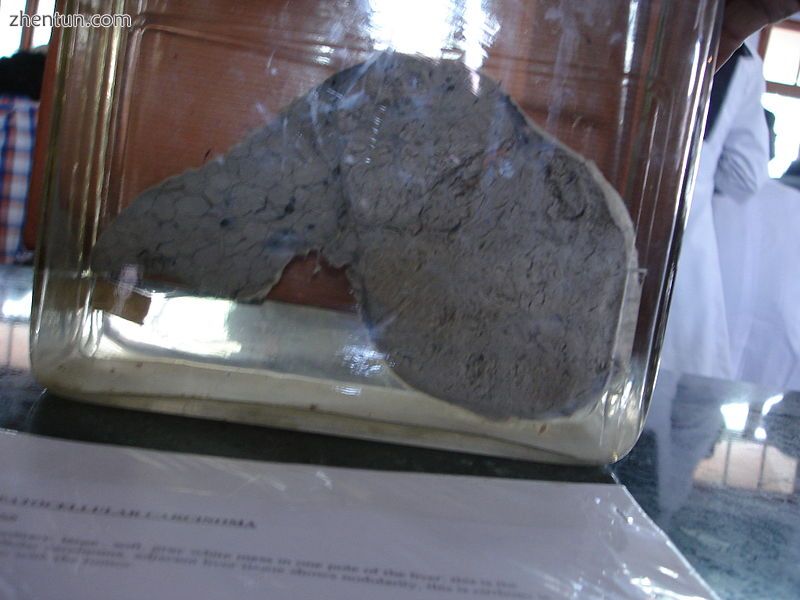

肝细胞癌的大体解剖

手术切除肿瘤与更好的癌症预后相关,但由于疾病程度或肝功能不良,只有5–15%的患者适合进行手术切除。仅在可以安全切除整个肿瘤并保留足够的功能性肝以维持正常生理的前提下,才考虑手术。因此,术前影像学评估对于确定HCC的程度和估计手术后剩余的肝脏残留量至关重要。为了维持肝功能,非肝硬化肝的残余肝体积应超过总肝体积的25%,而肝硬化肝的残余肝体积应大于总肝体积的40%。在患病或肝硬化的肝脏上进行手术通常会增加发病率和死亡率。切除后的总复发率为50-60%。新加坡肝癌复发评分可用于估计手术后复发的风险。

肝移植

肝移植用尸体或活体供体肝脏代替患病肝脏,在肝癌的治疗中起着越来越重要的作用。尽管最初进行肝移植后的预后很差(20%–36%的存活率[需要医学引用]),但随着外科手术技术的改善以及美国移植中心采用米兰标准,预后已大大改善。在中国扩大的上海标准导致整体生存率和无疾病生存率与使用米兰标准所达到的相似。 2000年代后期的研究得出较高的生存率,范围从67%到91%。

肝移植的风险超出了手术本身的风险。手术后为防止供体肝脏排斥而需要的免疫抑制药物也会损害人体抵抗功能异常细胞的天然能力。如果在移植前肿瘤未在肝脏外扩散,则药物可有效提高疾病进展速度并降低生存率。考虑到这一点,肝移植“可以作为无肝外转移的晚期HCC患者的治愈方法”。选择患者被认为是成功的关键。

烧蚀

射频消融(RFA)使用高频无线电波通过局部加热来破坏肿瘤。使用经皮,腹腔镜或开放式手术方法,在超声图像指导下将电极插入肝肿瘤。它适用于小肿瘤(<5厘米)。对于孤立肿瘤小于4 cm的患者,RFA效果最好。由于它是局部治疗,并且对正常健康组织的影响很小,因此可以重复多次。对于肿瘤较小的患者,生存期更好。在一项研究中,在302名患者的一系列研究中,> 5 cm,2.1至5 cm和≤2cm的病灶的三年生存率分别为59%,74%和91%。一项比较手术切除和RFA治疗小肝癌的大型随机试验显示,RFA治疗的患者具有相似的四年生存率和较低的发病率。

冷冻消融是一种用于使用低温破坏组织的技术。肿瘤没有被清除,被破坏的癌症被身体重新吸收。适当选择的无法切除的肝肿瘤患者的初步结果与切除的结果相同。冷冻手术涉及将不锈钢探针放置在肿瘤中心。液氮循环通过该设备的末端。将肿瘤和正常肝脏半英寸的边缘冷冻至190°C持续15分钟,这对所有组织都是致命的。将区域融化10分钟,然后再恢复至190°C 15分钟。肿瘤融化后,移开探针,控制出血,过程完成。病人在重症监护室度过了术后的第一晚,通常在3-5天出院。为了获得良好的结果和结果,必须正确选择患者并在进行冷冻手术时注意细节。通常,将冷冻手术与肝脏切除术结合使用,因为某些肿瘤已被清除,而另一些则接受了冷冻手术治疗。

经皮乙醇注射耐受良好,在小(<3 cm)的孤立性肿瘤中具有较高的RR;截至2005年,尚无随机试验将切除术与经皮治疗进行比较;复发率与切除后的相似。但是,一项比较研究发现,对于小肝癌患者,局部疗法可实现5年生存率,约为60%。

动脉导管治疗

经导管动脉化学栓塞术(TACE)用于不可切除的肿瘤,或作为等待肝移植(“移植桥”)的临时治疗方法。通过经由腹股沟动脉向右或左肝动脉注射与不透射线的造影剂(例如Lipiodol)和栓塞剂(例如Gelfoam)混合的抗肿瘤药(例如顺铂)和TACE,来完成TACE。该程序的目的是在提供靶向化疗药物的同时限制肿瘤的血管供应。已经证明,在超过米兰肝移植标准的患者中,TACE可以提高生存率并降低HCC的水平。接受该手术的患者将接受CT扫描,如果肿瘤持续存在,可能需要进行其他TACE手术。截至2005年,多项试验显示客观的肿瘤反应和减慢的肿瘤进展,但与支持治疗相比,其生存获益值得怀疑。在肝功能得以维持,无血管侵犯和肿瘤最小的人群中看到最大的益处。 TACE不适合大肿瘤(> 8 cm),门静脉血栓的存在,门静脉系统分流的肿瘤以及肝功能不佳的患者。

选择性内部放射疗法(SIRT)可用于从内部破坏肿瘤(从而最大程度地减少对健康组织的暴露)。与TACE相似,这是一种介入放射科医生选择性注射向肿瘤供应动脉或动脉的化疗药物的过程。该剂通常为掺入栓塞微球的Yttrium-90(Y-90),该栓塞微球驻留在肿瘤脉管系统中,引起局部缺血并将其辐射剂量直接传递至病变部位。该技术可以在不损害正常健康组织的情况下,将较高的局部辐射剂量直接传递给肿瘤。虽然不能治愈,但患者的生存率却有所提高。尽管回顾性研究表明相似的疗效,但尚无研究比较SIRT是否优于TACE。有两种产品可用,SIR-Spheres和TheraSphere。后者是FDA批准的原发性肝癌(HCC)治疗方法,已在临床试验中证明可提高低危患者的生存率。 SIR-Spheres已获得FDA批准,可用于治疗转移性结直肠癌,但在美国以外,SIR-Spheres已获批准用于治疗任何不可切除的肝癌,包括原发性肝癌。

系统性

对于已经扩散到肝脏以外的疾病,可能需要考虑全身治疗。 2007年,口服多激酶抑制剂索拉非尼是第一种被批准用于一线治疗晚期肝癌的全身性药物。试验发现总体生存率有所改善:分别为10.7个月和7.9个月以及6.5个月和4.2个月。

索拉非尼最常见的副作用包括手足皮肤反应和腹泻。索拉非尼被认为通过阻断肿瘤细胞和新血管的生长而起作用。许多其他分子靶向药物正在作为晚期HCC的替代一线和二线治疗方法进行测试。

其他

门静脉栓塞术(PVE):有时会使用此技术来增加健康肝脏的体积,以提高通过手术切除患病肝脏后的生存机会。例如,右主门静脉的栓塞将导致左叶的代偿性肥大,这可能使患者有资格进行部分肝切除术。放射介入医师使用经皮经肝方法进行栓塞。此过程也可以充当移植的桥梁。

高强度聚焦超声(HIFU)(与诊断超声相反)是一种实验技术,它使用大功率超声波破坏肿瘤组织。

系统评价评估了12篇文章,涉及318例接受Yttrium-90放射栓塞治疗的肝细胞癌患者。除了仅对一名患者进行的研究外,对肿瘤进行的治疗后CT评估显示有29%到100%的患者有反应,除两项研究以外,其他所有研究均显示71%或更高的反应。

预后

通常的结果很差,因为只有10-20%的肝细胞癌可以通过手术完全切除。如果无法完全清除癌症,则该疾病通常在3至6个月内致命。部分原因是由于晚期出现肿瘤,而且由于HCC患病率较高的地区缺乏医疗专业知识和设施。但是,生存时间可能会有所不同,有时人们的生存时间会超过6个月。由于索拉非尼(Nexavar)被批准用于晚期HCC,转移性或不可切除HCC的预后有所改善。

流行病学

肝癌是全世界最常见的肿瘤之一。肝癌的流行病学表现出两种主要模式,一种在北美和西欧,另一种在非西方国家,例如在撒哈拉以南非洲,中亚和东南亚以及亚马逊河流域。男性通常比女性受到的影响更大,而且最常见的年龄是30至50岁,每年全世界全世界肝癌的死亡人数为662,000,其中约一半在中国。

非洲和亚洲

在世界某些地区,例如撒哈拉以南非洲和东南亚,HCC是最常见的癌症,一般影响男性多于女性,发病年龄在十几岁至30岁之间。这种差异部分是由于不同人群中乙型肝炎和丙型肝炎的传播方式不同所致,出生时或出生前后的感染比早期感染的人更容易患癌症。从1970年至80年代的一项中国研究表明,从乙肝感染到发展为HCC的时间可能长达数年,甚至数十年,但从诊断HCC到死亡,平均生存期仅为5.9个月,即3个月。根据曼森的热带病教科书,在非洲撒哈拉以南地区。肝癌是中国最致命的癌症之一,在90%的病例中发现了慢性乙型肝炎。在日本,慢性丙型肝炎与90%的HCC病例有关。黄曲霉菌感染的食物(尤其是长时间潮湿的季节存放的花生和玉米)产生黄曲霉毒素构成了HCC的另一个危险因素。

北美和西欧

肝脏中最常见的恶性肿瘤代表源自身体其他部位的肿瘤的转移(扩散)。在源自肝组织的癌症中,HCC是最常见的原发性肝癌。在美国,美国的监测,流行病学和最终结果数据库程序表明,HCC占所有肝癌病例的65%。由于已经制定了针对慢性肝病高危人群的筛查计划,因此在西方国家发现HCC的时间通常比在撒哈拉以南非洲这样的发展中地区早得多。

急性和慢性肝卟​​啉症(急性间歇性卟啉症,皮肤卟啉卟啉菌,遗传性卟啉菌,杂斑性卟啉症)和I型酪氨酸血症是肝细胞癌的危险因素。对于没有典型乙型或丙型肝炎危险因素,酒精性肝硬化或血色素沉着病的HCC患者,应诊断为急性肝卟啉症(AIP,HCP,VP)。急性肝卟啉症的活性和潜在遗传携带者都有患这种癌症的风险,尽管潜在遗传携带者比具有典型症状的人更晚患癌症。急性肝卟啉症患者应进行肝癌监测。

在西半球,HCC的发生率比在东亚地区低。然而,尽管统计数字很低,但HCC的诊断自1980年代以来一直在增加,并且还在继续增加,使其成为由于癌症死亡的上升原因之一。肝癌的常见危险因素是丙型肝炎,以及其他健康问题。

研究

临床前

当前的研究包括寻找HCC中失调的基因,抗乙酰肝素酶抗体,蛋白质标记,非编码RNA(例如TUC338)和其他预测性生物标记。由于类似的研究正在其他各种恶性疾病中取得成果,因此希望鉴定异常基因和产生的蛋白质可能导致鉴定HCC的药理学干预措施。

三维培养方法的发展为使用源自患者的类器官的癌症治疗的临床前研究提供了一种新方法。这些患者肿瘤的微型类器官“化身”概括了原始肿瘤的几个特征,使其成为用于HCC和其他类型原发性肝癌的药物敏感性测试和精密药物的有吸引力的模型。

此外,肝癌发生在肝病患者中。一种名为六-miRNA签名的生物标记物可以有效治疗肝癌患者,并能够预测其在肝癌中的复发。

临床

JX-594是一种溶瘤病毒,具有针对这种情况的孤儿药名称,并且正在接受临床试验。

口腔癌疫苗Hepcortespenlisimut-L(Hepko-V5)也具有HCC的美国FDA孤儿药名称。 Immunitor Inc.完成了2017年发布的II期临床试验。

一项对晚期肝癌患者进行的随机试验显示,依维莫司和帕瑞肽联合使用无益处。

参考文献

Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J (2012). "Hepatocellular carcinoma". The Lancet. 379 (9822): 1245–1255. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. PMID 22353262.

Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A, eds. (2015). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (9th ed.). Saunders. pp. 870–873. ISBN 978-1455726134.

"Liver cancer overview". Mayo Clinic.

Heidelbaugh, Joel J.; Bruderly, Michael (2006-09-01). "Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure: part I. Diagnosis and evaluation". American Family Physician. 74 (5): 756–762. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 16970019.

Alter MJ (2007). "Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (17): 2436–41. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i17.2436. PMC 4146761. PMID 17552026.

White DL, Kanwal F, El-Serag HB (2012). "Association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and risk for hepatocellular cancer, based on systematic review". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 10 (12): 1342–59. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.10.001. PMC 3501546. PMID 23041539.

El–Serag HB; Hampel H; Javadi F (2006). "the association between diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 4 (3): 369–380. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.007. PMID 16527702. Diabetes is associated with an increased risk for HCC. However, more research is required to examine issues related to the duration and treatment of diabetes, and confounding by diet and obesity

Wang XW, Hussain SP, Huo TI, Wu CG, Forgues M, Hofseth LJ, Brechot C, Harris CC (2002). "Molecular pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma". Toxicology. 181–182: 43–47. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(02)00253-6. PMID 12505283. Recent studies in our laboratory have identified several potential factors that may contribute to the pathogenesis of HCC...For example, oxyradical overload diseases such as Wilson disease and hemochromatosis result in the generation of oxygen/nitrogen species that can cause mutations in the p53 tumour suppressor gene

Cheng W, Govindarajan S, Redeker A (1992). "Hepatocellular carcinoma in a case of Wilson's disease". Liver International. 12 (1): 42–45. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0676.1992.tb00553.x. PMID 1314321. The patient described here was the oldest and only the third female patient with hepatocellular carcinoma complicating Wilson's disease to be reported in the literature

Wilkinson ML, Portmann B, Williams R (1983). "Wilson's disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: possible protective role of copper". Gut. 24 (8): 767–771. doi:10.1136/gut.24.8.767. PMC 1420230. PMID 6307837. As copper has been shown to protect against chemically induced hepatocellular carcinoma in rats, this may be the reason for the extreme rarity of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with Wilson's disease and possibly in other liver diseases with hepatic copper overload

Huang YC, Tsan YT, Chan WC, Wang JD, Chu WM, Fu YC, Tong KM, Lin CH, Chang ST, Hwang WL (2015). "Incidence and survival of cancers among 1,054 hemophilia patients: A nationwide and 14-year cohort study". American Journal of Hematology. 90 (4): E55–E59. doi:10.1002/ajh.23947. PMID 25639564.

Shetty, Shrimati; Sharma, Nitika; Ghosh, Kanjaksha (2016-03-01). "Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in hemophilia". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 99: 129–133. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.12.009. ISSN 1040-8428. PMID 26754251.

Tanaka M, Katayama F, Kato H, Tanaka H, Wang J, Qiao YL, Inoue M (2011). "Hepatitis B and C virus infection and hepatocellular carcinoma in China: A review of epidemiology and control measures". Journal of Epidemiology. 21 (6): 401–416. doi:10.2188/jea.JE20100190. PMC 3899457. PMID 22041528.

"Pathophysiology". 2019-11-10. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

Hassan MM, Curley SA, Li D, Kaseb A, Davila M, Abdalla EK, Javle M, Moghazy DM, Lozano RD, Abbruzzese JL, Vauthey JN (2010). "Association of diabetes duration and diabetes treatment with the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma". Cancer. 116 (8): 1938–1946. doi:10.1002/cncr.24982. PMC 4123320. PMID 20166205. Diabetes appears to increase the risk of HCC, and such risk is correlated with a long duration of diabetes. Relying on dietary control and treatment with sulfonylureas or insulin were found to confer the highest magnitude of HCC risk, whereas treatment with biguanides or thiazolidinediones was associated with a 70% HCC risk reduction among diabetics.

Donadon, Valter (2009). "Antidiabetic therapy and increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 15 (20): 2506–11. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.2506. PMC 2686909. PMID 19469001. Our study confirms that type 2 diabetes mellitus is an independent risk factor for HCC and pre-exists in the majority of HCC patients. Moreover, in male patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, our data shows a direct association of HCC with insulin and sulphanylureas treatment and an inverse relationship with metformin therapy.

Donadon V, Balbi M, Ghersetti M, et al. (2009). "Antidiabetic therapy and increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic liver disease". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 15 (20): 2506–11. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.2506. PMC 2686909. PMID 19469001.

Siegel A, Zhu AX (2009). "Metabolic Syndrome and hepatocellular carcinoma". Cancer. 115 (24): 5651–5661. doi:10.1002/cncr.24687. PMC 3397779. PMID 19834957. The majority of 'cryptogenic' HCC in the United States is attributed to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome... It is predicted that metabolic syndrome will lead to large increases in the incidence of HCC over the next decades. A better understanding of the relation between these two diseases ultimately should lead to improved screening and treatment options for patients with HCC.

Stickely F, Hellerbrand C (2010). "Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma: mechanisms and implications". Gut. 59 (10): 1303–1307. doi:10.1136/gut.2009.199661. PMID 20650925. Based on the known association of NAFLD with IR and MS, approximately two-thirds of the patients were obese and/or diabetic, 4 and a remarkable 25% of these patients had no cirrhosis... Therefore, it is particularly worrying that the most persuasive evidence for an association between NAFLD and HCC derives from studies on the risk of HCC in patients with metabolic syndrome

"Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Diseases". Retrieved May 12, 2010.

Höpfner M, Huether A, Sutter AP, Baradari V, Schuppan D, Scherübl H (2006). "Blockade of IGF-1 receptor tyrosine kinase has antineoplastic effects in hepatocellular carcinoma cells". Biochemical Pharmacology. 71 (10): 1435–1448. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2006.02.006. PMID 16530734. Inhibition of IGF-1R tyrosine kinase (IGF-1R-TK) by NVP-AEW541 induces growth inhibition, apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human HCC cell lines without accompanying cytotoxicity. Thus, IGF-1R-TK inhibition may be a promising novel treatment approach in HCC.

Huynh H, Chow PK, Ooi LL, Soo KC (2002). "A possible role for insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 autocrine/paracrine loops in controlling hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation". Cell Growth & Differentiation. 13 (3): 115–122. PMID 11959812. Our data indicate that loss of autocrine/paracrine IGFBP-3 loops may lead to HCC tumor growth and suggest that modulating production of the IGFs, IGFBP-3, and IGF-IR may represent a novel approach in the treatment of HCC.

Martin NM, Abu Dayyeh BK, Chung RT (2008). "Anabolic steroid abuse causing recurrent hepatic adenomas and hemorrhage". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 14 (28): 4573–4575. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.4573. PMC 2731289. PMID 18680242. This is the first reported case of hepatic adenoma re-growth with recidivistic steroid abuse, complicated by life-threatening hemorrhage.

Gorayski P, Thompson CH, Subhash HS, Thomas AC (2007). "Hepatocellular carcinoma associated with recreational anabolic steroid use". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 42 (1): 74–75. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2007.03932. PMID 18178686. Malignant transformation to HCC from a pre-existing hepatic adenoma confirmed by immunohistochemical study has previously not been reported in athletes taking anabolic steroids. Further studies using screening programmes to identify high-risk individuals are recommended.

Shibata T, Aburatani H (2014). "Exploration of liver cancer genomes". Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 11 (6): 340–9. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2014.6. PMID 24473361.

Chien-Jen Chen; Hwai-I. Yang; Jun Su; Chin-Lan Jen; San-Lin You; Sheng-Nan Lu; Guan-Tarn Huang; Uchenna H. Iloeje (2006). "Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Across a Biological Gradient of Serum Hepatitis B Virus DNA Level". JAMA. 295 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1001/jama.295.1.65. PMID 16391218.

Yang SF, Chang CW, Wei RJ, Shiue YL, Wang SN, Yeh YT (2014). "Involvement of DNA damage response pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma". Biomed Res Int. 2014: 1–18. doi:10.1155/2014/153867. PMC 4022277. PMID 24877058.

Nishida N, Kudo M (2013). "Oxidative stress and epigenetic instability in human hepatocarcinogenesis". Dig Dis. 31 (5–6): 447–53. doi:10.1159/000355243. PMID 24281019.

Heimbach, Julie K.; Kulik, Laura M.; Finn, Richard; Sirlin, Claude B.; Abecassis, Michael; Roberts, Lewis R.; Zhu, Andrew; Murad, M. Hassan; Marrero, Jorge (2017-01-01). "Aasld guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma". Hepatology. 67 (1): 358–380. doi:10.1002/hep.29086. ISSN 1527-3350. PMID 28130846.

"Clinical features and diagnosis of primary hepatocellular carcinoma". UptoDate. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

Colli, A; Fraquelli, M; Casazza, G; Massironi, S; Colucci, A; Conte, D; Duca, P (March 2006). "Accuracy of ultrasonography, spiral CT, magnetic resonance, and alpha-fetoprotein in diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 101 (3): 513–23. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00467.x. PMID 16542288.

Ertle, JM; Heider, D; Wichert, M; Keller, B; Kueper, R; Hilgard, P; Gerken, G; Schlaak, JF (2013). "A combination of α-fetoprotein and des-γ-carboxy prothrombin is superior in detection of hepatocellular carcinoma". Digestion. 87 (2): 121–31. doi:10.1159/000346080. PMID 23406785.

El-Serag HB, Marrero JA, Rudolph L, Reddy KR (May 2008). "Diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma". Gastroenterology. 134 (6): 1752–63. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.090. PMID 18471552.

"Li-Rads". Archived from the original on 2017-07-11. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (Photo) ATLAS OF PATHOLOGY

Chan AW, Zhang Z, Chong CC, Tin EK, Chow C, Wong N (2019). "Genomic landscape of lymphoepithelioma-like hepatocellular carcinoma". J Pathol. 249: 166–172. doi:10.1002/path.5313.

Chan AW, Tong JH, Pan Y, Chan SL, Wong GL, Wong VW, Lai PB, To KF (2015). "Lymphoepithelioma-like hepatocellular carcinoma: an uncommon variant of hepatocellular carcinoma with favorable outcome". Am J Surg Pathol. 39 (3): 304–312. doi:10.1097/pas.0000000000000376.

Duseja, Ajay (2014-08-01). "Staging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hepatology. 4 (Suppl 3): S74–S79. doi:10.1016/j.jceh.2014.03.045. PMC 4284240. PMID 25755615.

Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J (1999). "Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification". Seminars in Liver Disease. 19 (3): 329–38. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1007122. PMID 10518312.

"BCLC staging system and the Child-Pugh system ;Liver cancer ; Cancer Research UK". cancerresearchuk.org.

"What is the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) staging?". medscape.

Kinoshita, A; Onoda, H; Fushiya, N; Koike, K; Nishino, H; Tajiri, H (27 March 2015). "Staging systems for hepatocellular carcinoma: Current status and future perspectives". World Journal of Hepatology. 7 (3): 406–24. doi:10.4254/wjh.v7.i3.406. PMC 4381166. PMID 25848467.

Katyal, Sanjeev; Oliver, James H.; Peterson, Mark S.; Ferris, James V.; Carr, Brian S.; Baron, Richard L. (2000). "Extrahepatic Metastases of Hepatocellular Carcinoma". Radiology. 216 (3): 698–703. doi:10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00se24698. PMID 10966697.

"Hepatitis B: Prevention and treatment". Archived from the original on 24 July 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2013. "WHO aims at controlling HBV worldwide to decrease the incidence of HBV-related chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. by integrating HB vaccination into routine infant (and possibly adolescent) immunization programs."

"Prevention". Retrieved May 12, 2010.

Kansagara, Devan; Papak, Joel; Pasha, Amirala S.; O'Neil, Maya; Freeman, Michele; Relevo, Rose; Quiñones, Ana; Motu'apuaka, Makalapua; et al. (17 June 2014). "Screening for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Chronic Liver Disease". Annals of Internal Medicine. 161 (4): 261–9. doi:10.7326/M14-0558. PMID 24934699.

Pompili, Maurizio (2013). "Bridging and downstaging treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients on the waiting list for liver transplantation". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (43): 7515–30. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i43.7515. PMC 3837250. PMID 24282343.

Gbolahan, Olumide B.; Schacht, Michael A.; Beckley, Eric W.; LaRoche, Thomas P.; O'Neil, Bert H.; Pyko, Maximilian (April 2017). "Locoregional and systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma". Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 8 (2): 215–228. doi:10.21037/jgo.2017.03.13. ISSN 2078-6891. PMC 5401862. PMID 28480062.

Marrero, JA; Kulik, LM; Sirlin, CB; Zhu, AX; Finn, RS; Abecassis, MM; Roberts, LR; Heimbach, JK (August 2018). "Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases" (PDF). Hepatology. 68 (2): 723–750. doi:10.1002/hep.29913. PMID 29624699.

Ma, Ka Wing; Cheung, Tan To (December 2016). "Surgical resection of localized hepatocellular carcinoma: patient selection and special consideration". Journal of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. 4: 1–9. doi:10.2147/JHC.S96085. PMC 5207474. PMID 28097107.

Ang, Soo Fan; Ng, Elizabeth Shu-Hui; Li, Huihua; Ong, Yu-Han; Choo, Su Pin; Ngeow, Joanne; Toh, Han Chong; Lim, Kiat Hon; Yap, Hao Yun; Tan, Chee Kiat; Ooi, London Lucien Peng Jin; Chung, Alexander Yaw Fui; Chow, Pierce Kah Hoe; Foo, Kian Fong; Tan, Min-Han; Cheow, Peng Chung (2015). "The Singapore Liver Cancer Recurrence (SLICER) Score for Relapse Prediction in Patients with Surgically Resected Hepatocellular Carcinoma". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0118658. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1018658A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118658. PMC 4382157. PMID 25830231.

Fan, Jia; Yang, Guang-Shun; Fu, Zhi-Ren; Peng, Zhi-Hai; Xia, Qiang; Peng, Chen-Hong; Qian, Jian-Ming; Zhou, Jian; Xu, Yang; et al. (2009). "Liver transplantation outcomes in 1,078 hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a multi-center experience in Shanghai, China". Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 135 (10): 1403–1412. doi:10.1007/s00432-009-0584-6. PMID 19381688.

Vitale, Alessandro; Gringeri, Enrico; Valmasoni, Michele; D'Amico, Francesco; Carraro, Amedeo; Pauletto, Alberto; D'Amico, Francesco Jr.; Polacco, Marina; D'Amico, Davide Francesco; Cillo, Umberto (2007). "Longterm results of liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an update of the University of Padova experience". Transplantation Proceedings. 39 (6): 1892–1894. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.05.031. PMID 17692645.

Obed, Aiman; Tsui, Tung-Yu; Schnitzbauer, Andreas A.; Obed, Manal; Schlitt, Hans J.; Becker, Heinz; Lorf, Thomas (2009). "Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Need for a New Patient Selection Strategy: Reply". Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 393 (2): 141–147. doi:10.1007/s00423-007-0250-x. PMC 1356504. PMID 18043937.

Cillo, Umberto; Vitale, Alessandro; Bassanello, Marco; Boccagni, Patrizia; Brolese, Alberto; Zanus, Giacomo; Burra, Patrizia; Fagiuoli, Stefano; Farinati, Fabio; Rugge, Massimo; d'Amico, Davide Francesco (February 2004). "Liver transplantation for the treatment of moderately or well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma". Annals of Surgery. 239 (2): 150–9. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000109146.72827.76. PMC 1356206. PMID 14745321.

Tanabe, KK; Curley, SA; Dodd, GD; Siperstein, AE; Goldberg, SN (February 1, 2004). "Radiofrequency ablation: the experts weigh in". Cancer. 100 (3): 641–50. doi:10.1002/cncr.11919. PMID 14745883.

Tateishi, R; Shiina, S; Teratani, T; Obi, S; Sato, S; Koike, Y; Fujishima, T; Yoshida, H; Kawabe, T; Omata, M (15 March 2005). "Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. An analysis of 1000 cases". Cancer. 103 (6): 1201–9. doi:10.1002/cncr.20892. PMID 15690326.

Chen, Min-Shan; Li, Jin-Qing; Zheng, Yun; Guo, Rong-Ping; Liang, Hui-Hong; Zhang, Ya-Qi; Lin, Xiao-Jun; Lau, Wan Y (2006). "A Prospective Randomized Trial Comparing Percutaneous Local Ablative Therapy and Partial Hepatectomy for Small Hepatocellular Carcinoma". Annals of Surgery. 243 (3): 321–8. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000201480.65519.b8. PMC 1448947. PMID 16495695.

Yamamoto, Junji; Okada, Shuichi; Shimada, Kazuaki; Okusaka, Takushi; Yamasaki, Susumu; Ueno, Hideki; Kosuge, Tomoo (2001). "Treatment strategy for small hepatocellular carcinoma: Comparison of long-term results after percutaneous ethanol injection therapy and surgical resection". Hepatology. 34 (4): 707–713. doi:10.1053/jhep.2001.27950. PMID 11584366.

"Interventional Radiology Treatments for Liver Cancer". Society of Interventional Radiology. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

Kooby, DA; Egnatashvili, V; Srinivasan, S; Chamsuddin, A; Delman, KA; Kauh, J; Staley CA, 3rd; Kim, HS (February 2010). "Comparison of yttrium-90 radioembolization and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for the treatment of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma". Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 21 (2): 224–30. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2009.10.013. PMID 20022765.

Llovet, Josep M.; Ricci, Sergio; Mazzaferro, Vincenzo; Hilgard, Philip; Gane, Edward; Blanc, Jean-Frédéric; de Oliveira, Andre Cosme; Santoro, Armando; Raoul, Jean-Luc (2008-07-24). "Sorafenib in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma". New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (4): 378–390. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.531.1130. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0708857. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 18650514.

Cheng, Ann-Lii; Kang, Yoon-Koo; Chen, Zhendong; Tsao, Chao-Jung; Qin, Shukui; Kim, Jun Suk; Luo, Rongcheng; Feng, Jifeng; Ye, Shenglong (January 2009). "Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients in the Asia-Pacific region with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a phase III randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". The Lancet. Oncology. 10 (1): 25–34. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70285-7. ISSN 1474-5488. PMID 19095497.

Kudo, Masatoshi (2017). "Systemic Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2017 Update". Oncology. 93 (1): 135–146. doi:10.1159/000481244. ISSN 0030-2414. PMID 29258077.

Madoff, DC; Hicks, ME; Vauthey, JN; Charnsangavej, C; Morello FA, Jr; Ahrar, K; Wallace, MJ; Gupta, S (September–October 2002). "Transhepatic portal vein embolization: anatomy, indications, and technical considerations". Radiographics. 22 (5): 1063–76. doi:10.1148/radiographics.22.5.g02se161063. PMID 12235336.

Vente MA, Wondergem M, van der Tweel I, et al. (April 2009). "Yttrium-90 microsphere radioembolization for the treatment of liver malignancies: a structured meta-analysis". European Radiology. 19 (4): 951–9. doi:10.1007/s00330-008-1211-7. PMID 18989675.

Hepatocellular carcinoma MedlinePlus, Medical Encyclopedia

"WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

Table 37.2 in: Sternberg, Stephen (2012). Sternberg's diagnostic surgical pathology. Place of publication not identified: LWW. ISBN 978-1-4511-5289-0. OCLC 953861627.

Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A (editors) (2015). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (9th ed.). Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 821–881. ISBN 9780323266161.

"Cancer". World Health Organization. February 2006. Retrieved 2007-05-24.

Rowe, JulieH; Ghouri, YezazAhmed; Mian, Idrees (2017-01-01). "Review of hepatocellular carcinoma: Epidemiology, etiology, and carcinogenesis". Journal of Carcinogenesis. 16 (1): 1. doi:10.4103/jcar.jcar_9_16. PMC 5490340. PMID 28694740.

Choo, Su Pin; Tan, Wan Ling; Goh, Brian K. P.; Tai, Wai Meng; Zhu, Andrew X. (15 November 2016). "Comparison of hepatocellular carcinoma in Eastern versus Western populations". Cancer. 122 (22): 3430–3446. doi:10.1002/cncr.30237. PMID 27622302.

Goh, George Boon-Bee; Chang, Pik-Eu; Tan, Chee-Kiat (December 2015). "Changing epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia". Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 29 (6): 919–928. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2015.09.007. PMID 26651253.

Yang, Jian-min; Wang, Hui-ju; Du, Ling; Han, Xiao-mei; Ye, Zai-yuan; Fang, Yong; Tao, Hou-quan; Zhao, Zhong-sheng; Zhou, Yong-lie (2009-01-25). "Screening and identification of novel B cell epitopes in human heparanase and their anti-invasion property for hepatocellular carcinoma". Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 58 (9): 1387–1396. doi:10.1007/s00262-008-0651-x. PMID 19169879.

Huntington Medical Research Institute News, May 2005 Archived 2005-12-10 at the Wayback Machine

Klingenberg, Marcel; Matsuda, Akiko; Diederichs, Sven; Patel, Tushar (September 2017). "Non-coding RNA in hepatocellular carcinoma: Mechanisms, biomarkers and therapeutic targets". Journal of Hepatology. 67 (3): 603–618. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.04.009. ISSN 1600-0641. PMID 28438689.

Braconi, C; Valeri, N, Kogure, T, Gasparini, P, Huang, N, Nuovo, GJ, Terracciano, L, Croce, CM, Patel, T (2011-01-11). "Expression and functional role of a transcribed noncoding RNA with an ultraconserved element in hepatocellular carcinoma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (2): 786–91. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108..786B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1011098108. PMC 3021052. PMID 21187392.

"Journal of Clinical Oncology, Special Issue on Molecular Oncology: Receptor-Based Therapy, April 2005". Archived from the original on 2005-11-30. Retrieved 2005-08-31.

Lau W, Leung T, Ho S, Chan M, Machin D, Lau J, Chan A, Yeo W, Mok T, Yu S, Leung N, Johnson P (1999). "Adjuvant intra-arterial iodine-131-labelled lipiodol for resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomised trial". The Lancet. 353 (9155): 797–801. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)06475-7. PMID 10459961.

Thomas M, Zhu A (2005). "Hepatocellular carcinoma: the need for progress". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 23 (13): 2892–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.196. PMID 15860847. Archived from the original on 2005-11-05. Retrieved 2005-08-29.

Broutier L, Mastrogiovanni G, Verstegen MM, Francies HE, Gavarró LM, Bradshaw CR, Allen GE, Arnes-Benito R, Sidorova O, Gaspersz MP, Georgakopoulos N, Koo BK, Dietmann S, Davies SE, Praseedom RK, Lieshout R, IJzermans JNM, Wigmore SJ, Saeb-Parsy K, Garnett MJ, van der Laan LJ, Huch M (2017). "Human primary liver cancer-derived organoid cultures for disease modeling and drug screening". Nat Med. 23: 1424–1435. doi:10.1038/nm.4438. PMC 5722201. PMID 29131160.

Fumao, B; Zhou, H; Ma, M; Guan, C; Lyu, J; Meng, QH (2 May 2018). "A novel RNA-sequencing-based miRNA signature predicts with recurrence and outcome of hepatocellular carcinoma". Molecular Oncology. 12 (7): 1125–1137. doi:10.1002/1878-0261.12315. PMC 6026871. PMID 29719937.

ennerex Granted FDA Orphan Drug Designation for Pexa-Vec in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Archived March 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

FDA Orphan Drug database

Tarakanovskaya, M. G; Chinburen, J; Batchuluun, P; Munkhzaya, C; Purevsuren, G; Dandii, D; Hulan, T; Oyungerel, D; Kutsyna, G. A; Reid, A. A; Borisova, V; Bain, A. I; Jirathitikal, V; Bourinbaiar, A. S (2017). "Open-label Phase II clinical trial in 75 patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma receiving daily dose of tableted liver cancer vaccine, hepcortespenlisimut-L". Journal of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. 4: 59–69. doi:10.2147/JHC.S122507. PMC 5396941. PMID 28443252.

Sanoff, Hanna K.; Kim, Richard; Ivanova, Anastasia; Alistar, Angela; McRee, Autumn J.; O’Neil, Bert H. (2015). "Everolimus and pasireotide for advanced and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma". Investigational New Drugs. 33 (2): 505–509. doi:10.1007/s10637-015-0209-7. PMC 4487887. PMID 25613083. |