概要

背景:男性包皮环切术(MC)被证明可以显著降低男性患多种性传播感染(STI)的风险。我们对科学文献进行了详细的系统评价,以确定MC与女性性传播感染风险和相关病症之间的关系。

方法:“割礼女性”和“割礼女性”的数据库检索确定了68篇相关文章。对这些书目的检查产生了14个其他出版物。每个都使用传统的评级系统评定质量。

结果:对所检索研究数据的评估表明,MC与女性感染致癌性人乳头瘤病毒(HPV)基因型和感染宫颈癌的风险降低有关。来自随机对照试验和其他研究的数据证实,伴侣MC不仅降低了女性患有致癌HPV的风险,还降低了阴道毛滴虫,细菌性阴道病和可能的生殖器溃疡病。对于单纯疱疹病毒2型,沙眼衣原体,梅毒螺旋体,人类免疫缺陷病毒和念珠菌病,证据不一。男性伴侣MC没有降低女性患淋病,生殖道支原体,排尿困难或阴道分泌物的风险。

结论:MC可降低女性致癌HPV基因型,宫颈癌,阴道毛滴虫,细菌性阴道病和可能的生殖器溃疡病的风险。这些性传播感染和宫颈癌风险的降低增加了支持全球努力将MC作为促进健康和拯救生命的公共卫生措施并补充其他性传播感染预防战略的数据。

关键词:女性,包皮环切术,男性,性传播感染,HIV,HPV,公共卫生,预防医学

介绍

性传播感染(STIs)对全球健康构成越来越大的威胁。世界卫生组织(WHO)发现,“全世界每天都有超过100万[性传播感染]被传染。每年,估计有3.57亿新的感染[...]衣原体,淋病,梅毒和毛滴虫病。估计有超过5亿人患有单纯疱疹病毒(HSV)的生殖器感染。超过2.9亿女性患有人乳头瘤病毒(HPV)感染“(1)。世界卫生组织强调,妇女的性传播感染通常没有症状,导致不良的分娩结果,可能增加艾滋病毒感染的易感性,可能具有长期发病率,在淋病的情况下表现出耐药性,并且可能导致不孕,母婴的风险儿童传播性传播感染,并增加过早死亡率(1)。艾滋病毒感染与多种并发症的风险增加有关(2)。美国性传播感染的患病率很高(3)。在2018年8月28日,疾病预防控制中心估计2017年美国将再发生20万例STI病例,警告“公共卫生危机”(4)。

对于HPV,全球患病率为11.7%,最高患病率在撒哈拉以南非洲(24%),东欧(21%)和拉丁美洲(16%)(5)。有大约200种HPV基因型,包括在肛门生殖器区域发生的超过40种基因型(6)。 2013 - 2014年全国健康和营养检查调查(NHANES)发现,在2174名年龄在18-39岁之间的女性中,37种HPV基因型中有一种或多种患病率为44.8%(7)。

几乎所有子宫颈鳞状细胞癌都是由致癌(“高风险”)HPV基因型引起的(8-11)。宫颈发育不良是第一个可见的异常,是宫颈癌的前兆。大多数情况下它会解决,但可能会缓慢发展为宫颈癌。几十年来,通过子宫颈抹片检查筛查(最近通过直接HPV检测),减少了富裕国家的宫颈癌,宫颈癌仍然是低收入国家女性死亡的主要原因(12)。新的生物标志物(12),例如p16INK4a(13),甲基化标志(14)和淋巴结转移检测技术(15)已经显示出筛选分类的希望。这包括老年妇女(16)。发育异常的辅因子可包括遗传或生活方式,尤其是吸烟。 2015年,全世界共有526,000例宫颈癌诊断和239,000例死亡(17)。由于缺乏HPV筛查和负担得起的治疗,这些死亡中有90%发生在低收入和中等收入国家(18)。在美国,预计2018年将有13,240例新诊断和4,170例宫颈癌死亡(19)。 2015年,宫颈癌导致700万残疾调整生命年(DALYs,即因健康不佳,残疾或早逝而丧失的生命年数),其中96%来自多年的生命损失,4%来自多年的生活残疾人(17)。对于低收入国家的所有癌症,宫颈癌丢失的相关DALYs仅次于口咽癌(2,252)(20)。

除子宫颈外,女性HPV相关的侵袭性癌症也发生在外阴,阴道,口咽,肛门和直肠(21)。在美国,每年有35,000例HPV相关癌症(女性占61%,男性占39%),每年监测和治疗HPV相关健康结果的费用为80亿美元(22)。除了直接的社会成本之外,卫生系统的成本,生理影响以及对个人和家庭的心理影响是间接成本,例如当前和未来收入的损失以及其他儿童提供医疗服务的成本。

对于HSV-2,患有这种感染的15-49岁人群的全球患病率超过4.17亿,2012年女性发病率为1200万,男性为700万(23)。根据2013 - 2014年美国NHANES数据显示,美国的HSV-2患病率为2,174名年龄在18-39岁之间的女性,占14.3%(非裔美国女性为39.8%,其他种族/种族女性为10.5%)(7)。

沙眼衣原体是继HPV后全球第二大STI,也是最常见的细菌性感染。世界卫生组织估计,每年有9200万新病例,其中300万发生在美国,每年照顾20亿美元(24)。

2013 - 2014年美国NHANES中有2,174名年龄在18-39岁之间的女性的沙眼衣原体患病率数据为2.2%(非裔美国女性为5.4%,其他种族/种族女性为1.7%)(7)。 2017年,每10万名美国女性各年龄段共有687例,女性分别在15-19岁和20-24岁女性中分别上升6.5%和3.7%(3)。自2000年以来,患病率每年都在增加,女性患病率是男性的两倍(25)。女性中未经治疗的沙眼衣原体导致多达10%的女性盆腔炎,对输卵管的炎性损害占美国女性不孕症的30%,并可引起异位妊娠(3)。沙眼衣原体感染是HPV诱导的宫颈癌的辅助因子(26),并且在两种性别中都是HIV传播。最近一项针对两个独立人群的血清学研究发现,针对沙眼衣原体(Pgp3)的抗体与卵巢癌风险增加有关(27)。

美国的淋病病例也有所增加,2015 - 2017年女性增加33%,每10万女性增加142例,在19岁儿童中达到872例/ 10万(3)。随着时间的推移,淋病对用于治疗它的常见抗菌药物的耐药性也有所增加,导致世界卫生组织将淋病称为“超级病菌”,这种“超级病菌”无法通过常用的有效抗生素(如环丙沙星)治疗,这些抗生素曾经是有效的治疗方法(28)。

阴道毛滴虫是全球另一种常见的性病。美国2013-2014 NHANES数据显示,4,057名年龄在18-59岁之间的女性发现阴道毛滴虫的患病率为1.8%(非裔美国女性患病率为8.9%,性传播感染风险高的人群,其他种族人群为0.8%)( 7)。在过去的一年中,对于≥2对0-1性伴侣的女性,患病率高出3.6倍(7)。澳大利亚悉尼郊区妇女的阴道毛滴虫患病率为3.4%(29)。阴道毛滴虫感染与人型支原体(Mycoplasma hominis)协同作用上调炎症,这可能增加宫颈癌和HIV获得的风险(30)。

全球女性梅毒患病率为0.56%,来自132个国家的数据显示,2012年至2016年期间,更多国家面临增加而不是减少(31)。世卫组织2018年的一份报告估计,“超过900,000名孕妇感染了梅毒,导致大约350,000例不良分娩结果,包括2012年的死产”(1)。在2013 - 2017年期间,美国女性的一级和二级梅毒率从每100,000名女性的0.9例增加到2.3例(3),增加了死亡率,孕妇死亡,早产和先天性感染(32)。在美国,梅毒负责420万DALYs(32)。

在2016年美国女性艾滋病病毒诊断总数中,异性恋收购占63%(6,541例)(33)。到2016年,154,584名美国女性患有3期HIV感染(艾滋病)(33)。在澳大利亚,女性艾滋病毒感染率稳步上升,2017年异性性交由导致25%的艾滋病毒诊断(34)。其中百分之六十六涉及与一个不在高流行率国家或从高流行率国家进行性交的人。肯尼亚记录了艾滋病毒感染率与财富之间的强烈正相关关系,其中女性艾滋病毒感染率在最低经济四分位数中为4%,最高为12%(35)。男性比女性更有可能拥有多个性伴侣,这是大多数女性可能的感染源(36)。如果没有有效的抗逆转录病毒治疗抑制艾滋病病毒复制,受感染的妇女可能会在怀孕和哺乳期间将艾滋病毒传染给她的后代。

细菌性阴道病(BV;以前称为加德纳菌属和“非特异性阴道炎”)是全世界女性最常见的生殖器感染之一。不同国家的BV患病率在8%到75%之间(37)。在美国,患病率在15%至49%之间,在性伴侣≥4的女性中更高(38)。已经观察到对常用抗生素的高水平抗性(38)。 BV症状可包括水样,白色或灰色分泌物而不是正常的阴道分泌物,以及来自阴道的强烈或不寻常的“鱼腥味”气味。 BV的特征在于阴道微生物群落的组成从正常的健康细菌 - 特别是产生乳酸的乳酸杆菌 - 随着各种其他细菌的过度生长而变化,特别是严格的厌氧菌,以及阴道液的pH(碱度)升高。 BV被一些人视为性传播(39),其流行病学与既定性传播感染相似(39,40)。一项荟萃分析发现,BV与宫颈癌前病变患病率高出51%(OR 1.5l; 95%CI 1.24-1.83)(41)。

控制所有性传播感染的承诺需要采取冷静的公共卫生措施,以“道德预防”为基础取代预防措施(32)。当一致和正确使用时,避孕套提供有效性的2级证据 - 即,从没有随机化的精心设计的对照试验和精心设计的队列或病例对照分析研究中获得的证据,优选由一个以上的中心或研究组(42) - 对大多数(但不是全部)STI(32)的至少部分(43,44)保护。

科学证据一致表明男性包皮过长(包皮)对感染的脆弱性(45)。包皮腔不仅捕获微生物,包皮空间具有好氧微生物组和含有感染因子靶细胞的大粘膜表面(45)。真皮包皮表面特别脆弱,促进了性传播感染的建立和持久性(46)。

近年来,记录男性包皮环切术(MC)的安全性和实质性健康益处的科学证据的数量和质量大幅增加,特别是在婴儿期早期(43,47-50),当福利超过风险时超过100比1(44,51)。益处始于预防尿路感染(52,53),尤其是先天性泌尿系统异常,如膀胱输尿管反流(52)。对男性的好处包括降低某些性传播感染的风险(54-58)。 MC对男性异性性感染HIV感染提供保护的早期证据(59-63)现已在最高标准的科学证据中得到证实,包括撒哈拉以南非洲的3个精心设计的大型随机对照试验(RCTs)(64 -66),系统评价(67),以及Cochrane委员会对MC试验结果的荟萃分析(68)。这导致MC被世界卫生组织和联合国艾滋病规划署认可为另一项重要干预措施,有助于减少艾滋病在流行病环境中的发病率(69)。推出自愿医疗MC(VMMC)计划已在高优先级国家(70个)实施了1890万MC程序,有助于减少感染和挽救生命(71)。 MC RCT随后发现男性其他几种性传播感染的风险降低(57)。由于MC对男性的益处现已确立,美国疾病控制和预防中心(CDC)(58)和美国儿科学会(48,72)制定了积极的政策建议,后者的政策得到了美国妇产科学院的认可。

预计男性性传播感染患病率较低会导致女性患病率降低,足以对女性公共卫生产生积极影响(73)。 VMMC在撒哈拉以南非洲(74-78)的流行病环境中非常有效地降低了两性的艾滋病毒感染率,在肯尼亚最近的一项研究(78)中高达50%,并且MC与人口之间存在相关性艾滋病在两性中的流行率(79),尽管这种生态观察存在局限性(80)。在血清不一致夫妇的研究中,当HIV病毒载量很高时,MC提供的保护作用最大(81)。

在这里,我们提供了关于男性包皮环切状态对性传播感染风险的影响以及随后对其女性性伴侣的生殖健康影响的科学证据的详细系统评价结果。

方法

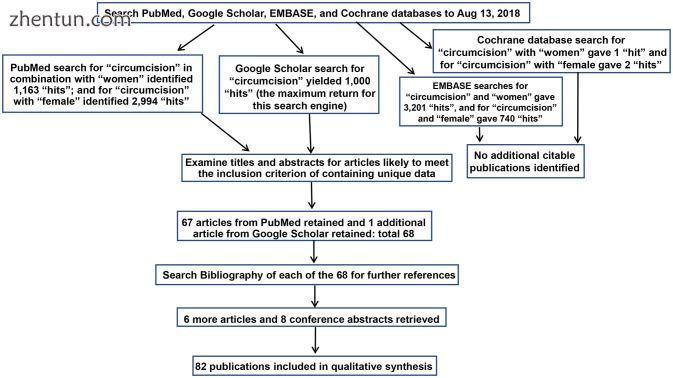

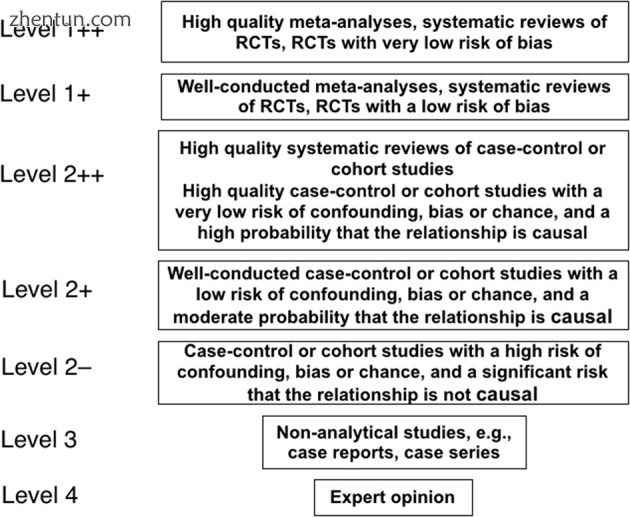

通过使用关键词(i)“割礼”和“女性”以及(ii)“割礼”和“女性”于2018年8月13日连续搜索PubMed,Google学术搜索,EMBASE和Cochrane系统评价数据库检索文章。有关性传播感染和妇女相关病症的出版物。表1中列出了特定的性传播感染和病症。以前的搜索中已经确定的结果未再包括在内。对标题和摘要进行了检查,并检查了可能符合纳入标准的文章的全文。图1显示了符合PRISMA指南的搜索策略(151)。评估文章的质量,并进一步研究苏格兰大学间指导网络(SIGN)评分标准(图2)(42)评级为“2”及以上的文章。然后引用了该主题最相关和最具代表性的内容。检查了参考书目以检索进一步的关键参考文献。

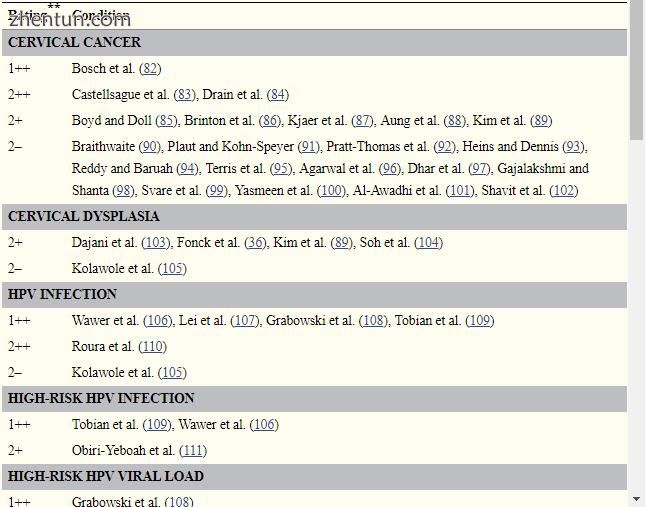

表格1

关于男性包皮环切术对女性伴侣宫颈癌和性传播感染影响的出版物,*以及质量评级**。

*对于接受过割礼的女性与未受割礼的性伴侣的女性。

**质量评级基于SIGN国际评级系统(42)。 1 ++高质量的荟萃分析,RCT系统评价或偏倚风险极低的RCT; 1+良好的荟萃分析,RCT系统评价或偏倚风险低的RCT; 1-荟萃分析,系统评价或随机对照试验,或具有高度偏倚风险的随机对照试验; 2 ++对病例对照或队列研究或高质量病例对照或队列研究进行高质量的系统评价,其混淆,偏倚或机会风险极低,且关系是因果关系的概率很高; 2+进行良好的病例对照或队列研究,混淆,偏倚或机会风险低,并且这种关系是因果关系的中等概率; 2-病例对照或队列研究具有混淆,偏倚或机会的高风险以及这种关系不是因果关系的重大风险。

图1

根据PRISMA指南(151)的要求搜索策略图。

图2

根据苏格兰校际指导网络(42)的规定,科学中用于评估索赔的证据质量等级。

结果和讨论

搜索结果

PubMed搜索为“割礼女性”产生了1,163次“点击”,为“割礼女性”获得了2,994次点击。Google Scholar产生了1,000次点击(此搜索引擎的最大回报)。 EMBASE为每个相应的搜索词提供了3,201和740次点击,Cochrane数据库1和2命中,但都没有产生额外的可引用文章。有关女性“割礼”更正确地称为“女性生殖器切割”或“切割女性生殖器官”(152)的出版物被排除在外。表1按主题列出了检索到的相关文章。其中包括PubMed的67个,以及Google Scholar的另一篇文章。 EMBASE和Cochrane搜索没有发现其他文章。对所选文章的参考书目的检查产生了6篇进一步的文章和8篇会议摘要。

人乳头瘤病毒和宫颈癌

观察研究

多年来积累了MC保护女性免受宫颈癌侵害的证据。 1901年,首次发现宫颈癌在犹太妇女中并不常见(90),这表明了一种文化因素。 1964年在伦敦对288名英国圣公会患者进行的一项研究发现,患有子宫颈癌的女性与未受割礼的男性结婚的可能性是其4倍(85)。然而,在1973年纽约的一项64例(95)的研究中,以及在中美洲国家的198名丈夫(12%包皮环切的)宫颈癌女性中,没有发现与MC无关(86)。

在1983年HPV被认为是宫颈癌的病原体之前(153),提出了包皮在包皮下的作用。 包皮垢是白色的皮脂分泌物,具有奶酪般的稠度,含有细菌,其他微生物,死皮细胞,粘液和其他成分。注射到马包皮瘤(91)或人类包皮瘤(每两周一次)(92,93)的小鼠的阴道腔中被发现诱导宫颈癌。短期暴露没有发现这种关联(94)。 1989年一项针对女性的研究发现,男性伴侣中的包皮垢与宫颈癌风险增加了51%相关(86)。

1987年的一项研究发现,患有宫颈癌的女性更可能患有阴茎上皮内瘤变(PIN),这是阴茎癌的前兆(154)。 1991年丹麦的一项研究发现,7名接受割礼的伴侣的女性中有1名(14%)患有宫颈癌,而未接受过割礼的男性伴侣的83名女性中有39名(47%)(87)。 1982年至1990年间,马德拉斯(现为钦奈)对5000例宫颈癌病例进行的一项研究显示,与非MC割礼的印度教徒(78.3)和基督教(63.2)女性(98)相比,穆斯林女性每24万人的发病率显著降低(24.5)。 一项病例对照研究对137名持续发育不良的女性进行了一项仅与一位伴侣发生性关系的女性发现与未接受过割礼的男性或在婴儿期后接受过包皮环切术的男性发生性关系的风险与宫颈癌风险增加4倍相关(96)。该研究控制了年龄,首次性交年龄和教育等因素。对克什米尔山谷各种类型癌症的研究得出结论认为,大多数穆斯林社区的普遍性MC导致宫颈癌发病率低于印度其他地区(97)。 1994年对女性宫颈癌,鳞状上皮内病变(SIL) - 以前称为宫颈上皮内瘤变(CIN)的女性在男性伴侣中发现的针对93%的病例(155)进行了一项研究。在约旦,在妇产科诊所的参与者中,男性伴侣的包皮环切术与SIL显著降低相关(103)。在2000年肯尼亚的一项小型研究中未发现与SIL或生殖器疣的关联(36)。

国际癌症研究机构于2002年在新英格兰医学杂志上发表的一项精心设计的多国研究中,令人信服的证据表明,包皮的存在是宫颈癌的一个危险因素(83)。该研究涉及欧洲,亚洲和南美洲5个地区的1,913对夫妇。阴茎HPV在20%的未割包皮的男性中被发现,但只有5%的包皮环切男性(调整后的比值比[OR] = 0.37; 95%CI 0.16-0.85)。在调整了男性和女性受试者的年龄,研究地点,第一次性交时的年龄,男性受教育程度,性交后男性生殖器冲洗的频率以及男性一生的性伴侣数量后,作者发现男性伴侣的一夫一妻制女性高性行为风险指数(6名或更多性伴侣和17岁以前的第一次性交)如果他们的伴侣接受了包皮环切术,患宫颈癌的风险降低了5.6倍(调整OR = 0.18; 95%CI 0.04-0.89)。一夫一妻制的女性,其伴侣具有中度性行为风险指数(在性伴侣之前≥6岁或在17岁之前首次性交),如果他们的伴侣接受包皮环切术,其患宫颈癌的风险降低2.0倍(调整OR = 0.50; 95% CI 0.27-0.94)。阴茎HPV感染与女性伴侣宫颈HPV感染风险增加4倍有关。宫颈HPV感染与宫颈癌风险增加77倍有关。

一项丹麦研究发现,接受过割礼的男性HPV患病率降低了5倍,结论:“接受过割礼的男性的女性伴侣较少接触宫颈癌,因为这些男性不太可能感染HPV”(99)。 2006年对来自117个发展中国家的联合国艾滋病规划署数据进行的一项研究显示,51个国家的子宫颈癌发病率为每10万妇女每年35例,MC患病率低(<20%),52个国家中每10万人中有20例(> 80%) )MC患病率(P <0.001)(84)。在所有检查的因素中,MC的缺失与宫颈癌发病率的关联最强。 2010年的一项研究发现印度农村穆斯林妇女完全没有宫颈癌(100)。与全球患病率11.7%(5)相比,以色列的低宫颈癌患病率部分归因于MC(102)。科威特,主要是穆斯林,男性在青春期之前接受过包皮环切术,其HPV感染率仅为2.3%,是世界上最低的之一(101)。在缅甸进行的一项研究发现,200名妇女宫颈癌在丈夫接受包皮环切术的妇女中较少见(P = 0.025)(88)。在韩国首尔,性伴侣MC与女性浸润性宫颈癌风险降低53%相关(OR = 0.47; 95%CI 0.24-0.90)(89)。一项针对3,261名女性的西班牙研究发现,如果男性伴侣接受包皮环切,那些有两个或两个以上终身性伴侣的人的HPV风险降低了40%(110)。在尼日利亚的一项研究中,未接受过割礼的男性伴侣的所有8名妇女的HPV血清学检测结果均为阳性,而接受过割礼的男性伴侣的这一比例为66%。前者细胞学异常的可能性是其13倍(105)。加纳2017年的一项研究发现,在艾滋病毒阴性妇女中,未受割礼的伴侣患高风险HPV的风险较高[相对风险(RR)= 1.9; 95%CI 1.1-3.5; P = 0.03]和HIV阳性的女性(RR = 1.4; 95%CI 1.2-1.6; P <0.0001)(111)。 2014年在肯尼亚对女性进行的一项研究显示,其中64%为艾滋病毒阳性,未发现MC与低级别和高级别宫颈异常发生率较高有关(104)。尼日利亚的一项研究发现,192名接受过包皮环切的男性伴侣的女性中有5%的细胞学检查异常,而未接受割礼的伴侣的女性比例为63%,差异为14倍;前者的HPV血清阳性率也降低了34%(105)。

对截至2007年9月完成的14项研究的荟萃分析(美国5项,墨西哥2项,澳大利亚2项,韩国,丹麦,英国,肯尼亚各1项,巴西,哥伦比亚,西班牙,泰国的跨国研究,和菲律宾)发现一夫一妻制妇女MC与宫颈癌之间的关联为0.75(95%CI 0.49-1.14)(82)。作者建议需要考虑男性伴侣风险评级,如Castellsague等人的跨国研究所做的那样。上面讨论过(83)。

随机临床试验

RCT是必要的,因为关联研究可能因MC实践以外的文化差异而受到混淆 - 例如,对有多个或同时伴侣的妇女的极端社会制裁可能与较慢的HPV传播相关,而不是没有这种制裁的社区。

来自三项随机对照试验的数据为MC保护男性免受高危HPV患病率和发病率的能力提供了明确的证据,并提高了HPV清除率(156-159)。乌干达的MC试验同时招募了女性伴侣。它涉及1,​​248对夫妇,干预组(男性伴侣包皮环切术)544名女性和对照组(未包皮环切术)488名患者获得随访数据,发现MC患病后24个月HPV患病率高达27.8%对38.7% ,分别为[事故风险比(IRR)= 0.72; 95%CI 0.60-0.85; P = 0.001](106)。 HPV发病率为20.7对比每100人年26.9例感染(IRR = 0.77; 95%CI 0.63至-0.93; P = 0.008)。总体而言,与未受割礼的伴侣相比,接受过割礼的男性的女性伴侣的高风险HPV患病率降低了28%(106)。

在乌干达试验中,一个伴侣的基因型特异性HPV负荷与1年后另一个伴侣中新检测到相同基因型的风险相关(108)。与未受割礼的伴侣相比,接受过割礼的伴侣的女性HPV检出率低58%。与未割包皮的男性的女性伴侣相比,接受过割礼的男性的女性伴侣获得的基因型较少,而且清除率也增加。男性病毒“减少”的减少被认为是割礼男性女性伴侣HPV减少的原因(160)。在未病毒包埋的男性病毒载量高的情况下,高风险HPV16和HPV18的清除率较低,从而增加了HPV向女性伴侣传播的风险(112)。除了较低的致癌HPV感染风险外,乌干达RCT中接受过包皮环切手术的女性伴侣的HPV病毒载量较低,这完全是由24个月随访期间新发的高危HPV感染引起的(PRR = 0.66; 95%CI 0.50-0.87,P = 0.003)(113)。

艾滋病毒感染者的包皮环切术并未影响高风险或低风险HPV向其女性伴侣的传播(109)。

在乌干达试验中,接受过包皮环切手术的男性女性伴侣的低风险HPV患病率降低了32%(IRR = 0.68; 95%CI 0.53-0.89)(106)。

传输方式

生殖器HPV基因型具有高度传染性,可以感染生殖器区域的皮肤。不一定延伸到性交的皮肤接触仍然可能导致感染(161)。多发性包皮过长或包茎是HPV感染的独立危险因素(OR = 3.4; 95%CI 2.5-4.6),在HPV感染的50.9%女性的78.6%的男性性伴侣中发现在中国南京的一项研究(162)。

虽然未经过包皮环切的男性在欧洲,亚洲和南美洲国家的多国研究中性交后更频繁地洗了他们的生殖器,但是经医生评估,割礼的男性有更好的阴茎卫生(83)。有人提出,未受割礼的男性更容易被感染,因为在性交过程中,包皮内部(粘膜)更细腻的内层完全暴露于阴道分泌物。性交后,一种传染性接种物可能被困在包皮层内,并从表面上皮细胞传递到基底层,在那里发生鳞状细胞向基底细胞的变化。粘膜表面对HPV感染的脆弱性也适用于子宫颈,特别是女性的过渡区。

总之,有强有力的证据表明,接受包皮环切的男性伴侣可以大大降低女性HPV感染的风险,从而降低宫颈癌,HPV依赖性疾病和其他HPV病因较少的生殖器癌的风险。

单纯疱疹病毒2型

宾夕法尼亚州匹兹堡的一项2003年研究显示,1,207名年龄在18-30岁的女性,其总体HSV-2血清阳性率为25%,发现与未受割礼的男性性交史(曾经)增加了HSV-2感染的风险2- fold(或来自多变量逻辑回归分析= 2.2; 95%CI 1.4-3.6)(116)。 9个国家的HSV-2流行率较低,其中MC患病率> 10%,而10个国家的MC患病率<20%(分别为30.1%和42.9%,P> 0.05)(84)。印度的一项研究发现,接受过割礼配偶的女性患HSV-2的患病率为1.7%,而配偶未婚的女性则为9.2%(OR = 5.7; 95%CI为1.4-23.4; P = 0.01)(117)。同样,一项针对4,766名年龄在15-49岁的女性的南非研究发现,在两名年轻女性(49%对62%; P <0.01)和年长女性(83岁对比)中,割礼男性伴侣的HSV-2患病率较低。 86%; P = 0.04)(119)。患有包皮环切男性伴侣的老年女性患STI的可能性较小(7%对11%; P <0.01)(119)。在肯尼亚的8,953名女性中,有接受过割礼的伴侣的HSV-2患病率为39.4%,未接受包皮环切的伴侣的女性为77.4%(P <0.001)(115)。在该研究中,HIV阳性与HIV阴性的女性相比,HSV-2感染的风险高7.5倍。然而,一项涉及撒哈拉以南非洲7个国家14个地点的研究发现,MC对女性伴侣中HSV-2感染的保护作用微乎其微(PRR = 0.94; P = 0.49)(118)。在乌干达的一项随机对照试验中,368名接受过割礼的男性的女性伴侣的风险降低了15%(114)。在肯尼亚的一项研究中,14名接受割礼的妇女和14名未受割礼的伴侣的妇女在HSV-2相关的生殖器溃疡方面没有差异(120)。

总之,有大量观察性研究的证据,但不是来自试验数据和其他一些研究,表明MC可能减少HSV-2感染和女性患病率。

生殖器溃疡病

在乌干达MC RCT中接受包皮环切男性伴侣的妇女生殖器溃疡病风险降低22%(校正PRR = 0.78; 95%CI 0.63-0.97)(123)。然而,随后的分析发现没有差异(122)。来自另一项RCT的二手数据显示,在女性的67%的生殖器溃疡中确定了病原体,其中96%的女性将HSV-2作为主要病原体(121)。大多数患有HSV-2的女性在试验开始时已经感染,并且在他们的拭子中检测到HSV-2代表了现有感染的再激活(121)。 2000年肯尼亚的一项小型研究发现,女性中伴侣MC和HSV-2之间没有关联(36)。

沙眼衣原体

对全球5个不同国家的305对夫妇进行的一项多国研究发现,未接受过包皮环切的男性伴侣有6个或更多性伴侣的女性患沙门氏菌抗体的风险增加5.6倍,而有性行为相似的女性患者的性行为相似( 124)。通过测量抗体来评估终身暴露,本研究发现,对于接受过包皮环切术与未受割礼的伴侣的妇女,抗肺炎衣原体(一种非性传播的衣原体)抗体的频率没有差异,支持了MC的保护作用。减少女性沙眼衣原体感染风险(124)。

印度的一项研究发现,在接受过包皮环切的男性伴侣的女性中,沙眼衣原体的患病率为9%,而未接受过割礼的男性伴侣的女性则为21%(127)。匹兹堡和北卡罗来纳州一项研究中血清学数据的多变量分析发现,在过去3个月中与未割包皮的男性发生过性行为的女性患沙门氏菌的风险高2.6倍(95%CI 1.21-5.82)(126 )。

感染沙眼衣原体的子宫颈阴道分泌物在未包皮环切的男性中被包裹在包皮下可能会增加阴茎尿道感染的风险,并且在性交过程中将沙眼衣原体传染给女性(124)。然而,对男性观察性研究数据的荟萃分析表明,MC不能预防衣原体和其他尿道性呼吸综合症(163)。男性随机对照试验数据一直存在矛盾,南非MC RCT发现明显减少44%(164),但肯尼亚MC RCT未发现明显减少(165)。

其他女性研究未发现沙眼衣原体感染与伴侣MC状态之间的关联。其中包括2000年肯尼亚的一项小型研究(36),2016年肯尼亚,乌干达和南非的研究(128),以及2008年乌干达,津巴布韦和泰国的5,925名妇女的前瞻性研究(125)。

总之,有证据表明和反对MC与女性沙眼衣原体感染风险降低有关。鉴于女性沙眼衣原体缺乏一致的RCT数据,因此需要进一步的试验。

淋病奈瑟菌

2000年来自肯尼亚的一项小型研究(36)和乌干达,津巴布韦和泰国的5,925名妇女(125)或肯尼亚妇女研究中没有发现女性伴侣的MC状态和淋病之间存在关联。 ,2016年,乌干达和南非(128)。然而,2014年在印度进行的一项涉及61名女性的研究显示,接受过包皮环切男性伴侣的女性缺乏淋病,但有未接受过割礼的伴侣的女性中有7.1%存在淋病(127)。

总之,几乎没有证据表明伴侣MC状态可以降低女性的淋病风险。这是可以预期的,因为MC状态对男性性传播性尿道炎没有影响(163)。

阴道毛滴虫

乌干达RCT的结果显示,825名接受过割礼的男性妻子的阴道毛滴虫患病率(调整后的PRR = 0.52; 95%CI 0.05-0.98)比未受割礼的男性783名妻子减少了48%(123)。有人提出,感染途径可能涉及潮湿的亚上空间,可能会增强阴道毛滴虫的存活和传播(123)。在981对夫妇中,来自7个非洲国家的14个地点,其中至少有一个伴侣被感染,在多变量分析中,患有包皮环切男性伴侣的妇女在阴道毛滴虫感染风险方面降低了18%(P = 0.004)。一项较小的乌干达研究显示,138名和112名女性伴侣接受了包皮环切术与非未割包皮治疗的男性合作,结果发现女性阴道毛滴虫患病率分别为7%和15%(P = 0.056)(129)。然而,2000年肯尼亚520名妇女(36名)的研究中没有发现任何关联,2008年的多国研究也没有发现这种关联(125)。

总之,特别是基于RCT数据,MC可能与女性滴虫病风险降低有关,但需要进一步研究。

梅毒(梅毒螺旋体苍白球)

2000年肯尼亚的一项小型研究发现女性MC状态与梅毒感染无关(36)。在坦桑尼亚的663名孕妇中,女性的梅毒血清阳性率在接受包皮环切术的男性中低于未受割礼的男性伴侣[1.3%对4.7%;单变量和多变量OR = 3.8(分别为P = 0.001和0.01)](131)。在肯尼亚,乌干达和南非进行的一项研究显示,有1,561名接受过割礼的伴侣的妇女和2,863名未受割礼的伴侣的妇女发现梅毒风险降低[风险比(HR)= 0.51;当合作伙伴接受包皮环切时,虽然在过去7天内报告的性行为数量存在重大差异,并且最后一次性行为中使用安全套可能会影响调查结果,因此95%CI 0.26-1.00,P = 0.058] 128)。南非一项针对15-49岁女性的研究发现,男性伴侣MC状态与梅毒血清学呈负相关(分别为1.5%和3.4%;对于未经过割礼的未受割礼的伴侣,P = 0.04)(119)。一项针对2,946例艾滋病毒阴性夫妇的大型前瞻性队列研究发现,梅毒患者的梅毒患者中,梅毒的发病率低于75%(130)。在印度的一项小型研究中,男性患有包皮环切的男性伴侣的梅毒缺席,而未患未割包皮的男性伴侣的女性则为3.5%(127)。

总之,这些发现提供了证据表明MC可能有助于保护女性免受梅毒的侵害。需要进一步的研究来确定这种保护作用的精确程度。

下疳(Hemophylus ducreyi)

我们没有发现女性MC和软下疳的研究。然而,有人指出,在非洲南部和东部地区,MC患病率低且艾滋病病毒感染率很高,软下疳是地方性的,软下疳与性工作密切相关,而软下疳是艾滋病毒感染的一个强风险因素。 (166)。近年来,世界许多地区的软下疳患病率下降(167)。

人类免疫缺陷病毒

关于性伴侣MC身份可能降低女性艾滋病风险的调查结果各不相同。在卢旺达,1994年的一项研究发现,在多变量回归分析后,一夫一妻和高风险妇女在接受包皮环切术与非未割包皮的伴侣(24.4%对8.4%)中的HIV血清阳性率有统计学差异,相似(每2.2倍)(132 )。相比之下,1991年卢旺达的一项研究没有报道任何关联(143),当控制其他协变量时,较高的社会经济地位和多个性伴侣也是风险因素。 1994年对肯尼亚4,404名妇女进行的一项研究发现,接受包皮环切术与非割礼合作伙伴的妇女艾滋病毒感染率降低2.9倍(4.2%对11.5%)(133)。该研究中的大多数女性在前一年仅报告了一位合作伙伴。与伴侣MC状态相关的HIV风险发生在研究中几乎所有潜在混杂因素中。 1998年在坦桑尼亚达累斯萨拉姆进行的一项研究表明,如果丈夫未受割包皮,已婚妇女与一个性伴侣的艾滋病相对风险要高4倍(134)。肯尼亚2000年的一项研究发现,未受割礼的伴侣妇女的艾滋病毒感染率高出2倍(36)。虽然津巴布韦妇女的割礼伴侣的艾滋病毒感染率降低了31%,但调整潜在的混杂因素使这种关系变得不重要(135)。 2010年对来自东非7个地点的1,096名血清不一致夫妇进行的一项研究显示,艾滋病毒阳性包皮环切男性的女性伴侣艾滋病毒感染率降低了38%(P = 0.10)(137)。

乌干达拉凯的一项随机对照试验显示,在受割礼时已经感染艾滋病毒的男性未受感染的女性伴侣,记录了17名感染的女性,其伴侣在基线时接受了包皮环切术,8名女性的伴侣的割礼延迟了24个月( 18比12%;调整风险比1.49; P = 0.37)(129)。由于艾滋病病毒感染者的MC在24个月内没有减少艾滋病病毒传播给女性伴侣,因此在中期分析中该试验因“无效”而停止。因此,“无法评估”长期效应。“虽然总体上没有发现统计学上显著的差异,但值得注意的是,在6个月的第一次随访时,28%的受伤男性在伤口愈合前恢复性行为的女性伴侣已经获得艾滋病毒,相比之下,9.5%的男性伴侣性行为迟钝,直到愈合完成(P = 0.038)(129)。在建议的6周愈合期之前恢复性行为是解释这些发现的重要因素(129,168)。后来计算出10,000名血清不一致夫妇需要登记以检测显著效果,这项任务被认为是“后勤上不可行的”(169)。

在津巴布韦和坦桑尼亚的657名孕妇中,艾滋病毒在伴侣接受包皮环切术和未接受包皮环切术的女性中没有显著差异(分别为7.1%和11.5%)(144)。在一项针对13个撒哈拉以南非洲国家的研究中,MC的区域性MC患病率与女性的HIV患病率显著降低相关(中高MC患病率分别调整OR = 0.27和0.10,低MC患病率;每个P < 0.001)(136)。在艾滋病流行率最高的马拉维南部而非北部农村地区,拥有割礼伴侣的妇女的艾滋病毒感染率是其他妇女的一半(逻辑回归模型P <0.05)(138)。对来自非洲东部和南部14个地点的2,223名妇女进行的一项研究显示,男性伴侣割礼状态与女性艾滋病毒感染率降低47%显著相关(139)。涉及青春期前接受过包皮环切术的男性的观察性研究表明,女性对女性的保护作用强于成年人接受过包皮环切术的男性随机对照试验数据(147)。在有性行为的5,561名女性中,30%曾经接受过割礼的伴侣的艾滋病毒感染率较低(22.4%对36.6%;调整后的PRR = 0.85; P = 0.004)(141)。

坦桑尼亚的一项研究发现,在大多数男性接受割礼的地区,女性的艾滋病毒负担可能更高,因此建议与VMMC一起,需要艾滋病预防工作吸引女性(79)。坦桑尼亚的另一项研究发现,接受过割礼的伴侣的孕妇艾滋病病毒感染率显著降低了18%(131)。

对一项随机对照试验和6项纵向研究至2009年8月的数据的荟萃分析发现,MC与女性20%的非显著性降低相关(总结RR = 0.80; 95%CI 0.54-1.19)(169)。 2015年仅限于随机对照试验和队列研究的荟萃分析发现,接受过包皮环切男性伴侣的女性艾滋病风险降低32%(汇总调整后的RR = 0.68; 95%CI为0.40-1.15; P = 0.15)(107)。

在Orange Farm(前南非MC RCT的网站)的VMMC部署中,在4538名年龄在15-49岁之间的女性中,显著降低了16.9%(调整后的IRR = 0.83; 95%CI为0.011-0.69)。那些只接受过割礼的男性伴侣的人(140)。然而,另一项南非研究发现,调整后,MC与女性艾滋病风险降低无关(146)。一项针对1,356名艾滋病毒阴性孕妇的南非队列研究发现,调整后的艾滋病毒感染率降低了78%,而在接受过割礼与未受割礼的伴侣的妇女中,这一比例没有统计学意义(142)。进一步的南非研究涉及4,766名女性,发现伴侣MC与女性的艾滋病毒感染率显著降低相关(24%对35%; P <0.01)(119)。

在可比较的高收入国家,MC患病率较低的国家(荷兰和法国)异性性感染艾滋病毒的患病率是女性的10倍(男性高6倍),而以色列是一个非常高的国家MC患病率(145)。

直觉上,人们一直认为,如果一个人是艾滋病病毒阳性,无论他是否接受过割礼,对于他的性伴侣的艾滋病毒感染风险应该没什么影响(135)。然而,在高风险环境中的女性患者中发现了一个例外(HR = 0.16)。 2000年乌干达的一项研究发现,男性伴侣的病毒载量<10,000和10,000-49,999拷贝/ ml与HIV发病率相关/ 100人年6.9(95%CI 2.8-11.0)和12.6(95%CI) 6.8-18.4)分别对未受割礼的男性伴侣的女性(61)。接受过包皮环切的男性伴侣的女性没有感染。但如果男性的HIV病毒载量≥50,000拷贝/ ml,则每100人年的HIV发病率没有差异:25.0(95%CI 0.50-49.5)与接受包皮环切术的女性25.6(95%CI 15.4-35.8)不同与未受割礼的伴侣(61)。

女性HIV感染的机制

女性生殖道的几个特征增加了暴露,感染的建立和病毒的系统性传播后获得HIV的可能性,导致局部变化有利于其他性传播感染(170)。艾滋病毒与其他性传播感染感染之间的这种双向协同关系增加了艾滋病毒的局部复制(171)。艾滋病毒阳性妇女的生殖道不仅从艾滋病毒中分离出艾滋病毒,生殖器溃疡妇女的艾滋病病毒脱落率增加(172),生殖器溃疡使女性的艾滋病毒风险增加8.5倍(173)。然而,在RCT中对女性进行HSV-2抑制治疗并未降低其获得HIV的风险(174)。

无论MC是否对女性伴侣的艾滋病病毒传播有直接影响,因此艾滋病病毒感染者的艾滋病毒感染率会长期下降,从而减少艾滋病毒传播给女性,从而间接受益于妇女的MC扩大规模( 175,176)。联合国艾滋病规划署估计,在非洲,MC的每增加5%,女性的艾滋病毒感染率将下降2%(177)。

总之,尽管MC似乎没有直接减少女性的HIV感染,但由于它减少了男性的HIV感染率,因此降低了男性的人群水平(参见引言部分),这降低了妇女感染风险。

细菌性阴道病

美国在Pittsburg对773名没有BV的女性进行了一项纵向研究,结果发现超过1年的未受割礼的伴侣患有BV的可能性是其两倍(148)。乌干达的一项随机对照试验发现BV总体上降低了40%(调整后的PRR = 0.60; 95%CI为0.38-0.94),严重的BV降低了69%(调整后的PRR = 0.31; 95%CI为0.18-0.54),受割礼的男人的妻子(123)。在这种情况下,艾滋病毒感染者的女性伴侣的BV率没有差异(129)。 2000年肯尼亚的一项小型研究没有发现任何关联(36)。在一项印度研究中,有4.5%的女性接受了包皮环切的伴侣,而在未受割礼的伴侣中,有7.1%的女性被发现(127)。美国的两项小型低功率研究发现,女性的BV风险与男性伴侣的包皮环切状态无关(149,150)。

男性包皮可以促进BV相关生物的存活,例如革兰氏阴性厌氧细菌,从而使这种细菌更有效和更长时间地传播给性伴侣(39)。在大型RCT中男性的微生物组显示出MC前男性包皮下革兰氏阴性厌氧菌的流行率更高(147)。 MC通过减少阴茎促炎性厌氧细菌,降低女性伴侣的BV风险(147)。

未经过包皮环切的男性伴侣的女性生殖器溃疡含有较高的BV推定细菌因子(120)。在14个细菌分类群中,只有加德纳菌(Gardnerella taxa)因男性伴侣MC状态而显著不同(减少71%)(120)。

一项荟萃分析发现BV与牙周病之间存在正相关关系(178)。

与未受割礼的伴侣接受口交与牙周病相比,牙周病风险高1.3倍(178)。

总之,大多数证据,包括高质量的RCT数据,都表明MC与女性BV风险降低有关。

其他性传播感染和疾病

肯尼亚520名女性的念珠菌降低了40%,其男性伴侣接受了包皮环切术(OR = 0.6; 95%CI 0.4-1.0)(36)。生殖支原体(122),排尿困难(123,129)和阴道分泌物(122,123,129)的女性伴侣没有减少。

MC在其他STI减少手段的背景下

避孕套

避孕套提供针对各种性传播感染的保护,不同的性传播感染类型和使用的一致性有效性不同(179)。如果一致和正确使用,避孕套可提供80%(180)至71-77%(181)的HIV感染保护(180,182)。在印度迈索尔进行的一项研究发现,在其伴侣最后一次性交使用安全套的40名女性中,艾滋病毒感染率显著高于2,225名伴侣不使用安全套的女性(调整后的OR = 10.5; 95%CI) 2.05-53.8;多变量分析后P <0.01)(183)。在这项研究的男性中,曾经使用安全套与艾滋病毒感染率较高有关(校正OR = 2.7; 95%CI 1.0-7.5; P = 0.05)。据报道,只有12%的男性曾使用安全套。对这些研究结果的解释是,具有高风险行为的人首先感染了艾滋病毒,然后在了解了他们的艾滋病毒感染并意识到他们的高危行为后,开始使用安全套。在13个非洲国家的研究中,同样的推理被用来解释为什么安全套的使用与艾滋病毒感染几率降低无关(136)。对使用安全套的RCT进行的Cochrane系统评价和荟萃分析(美国2例,英格兰1例,非洲4例)发现“有效的临床证据很少”,艾滋病预防没有“有利结果”(184)。膈肌 - 女性通常用作避孕药 - 不能预防艾滋病毒感染(185)。

在Castellsague等人的多国研究中,MC对宫颈癌减少的影响在避孕套使用者(OR = 0.83; 95%CI 0.37-1.87)和非使用者(OR = 0.67; 95%CI 0.44-1.02)之间差异不大)(83)。在这项研究和其他研究中,安全套仅提供了针对HPV感染的轻微保护(83,106,110)。然而,一项针对西雅图大学本科生的研究发现,与合作伙伴使用安全套的女性相比,使用安全套的女性的HPV发病率降低了70%(186)。伴侣总是使用避孕套的女性不存在鳞状上皮内病变,而非使用者则为每100人年14。在接受过宫颈鳞状细胞病变治疗的女性中,使用一致的安全套可将高危HPV感染率降低82%(95%CI 0.62-0.91)(187)。 2014年的一项系统评价发现了4项研究,其中避孕套对HPV感染提供了统计学上显著的保护,4项保护没有达到统计学意义(188)。

在肯尼亚的一项大型研究中,使用安全套并不能保护女性免受HSV-2的侵害(115)。 Cochrane分析发现安全套在预防梅毒感染方面有42%的效果(184)。在美国的一项研究中,使用避孕套和偶尔的伴侣提供了对BV的保护(RR = 0.80; 95%CI 0.67-0.98; P = 0.003)(149)。

在美国,16%的男性和非主要伴侣中24%的女性在异性性行为期间从未使用安全套(189)。美国一项针对巴尔的摩STI诊所妇女的调查发现,使用安全套的比例为25%,其中48%表示在过去的14天内没有使用安全套(190)。然而,对阴道中的男性DNA进行测试表明,DNA存在于所有女性中,尽管在表示不使用避孕套的组中存在较高的DNA(190)。 2000年“柳叶刀”杂志的一篇评论报道,使用安全套的比例为55%(191)。在年轻人中,澳大利亚的一项研究发现,只有25%的人使用安全套,其中25%从未使用安全套(192)。墨西哥的一项调查显示,年轻男性使用安全套的比例为51%,而年轻女性则报告为23%(193)。在这项研究中,使用安全套的比例仅为30%(193)。在13,293名墨西哥公立学校学生中,平均性初始年龄为14岁,其中37%为高,46%为中等艾滋病毒/艾滋病知识(194)。知识渊博的男性更可能使用避孕套(OR = 1.4),而此类女性不太可能确保男性伴侣使用安全套(OR = 0.7)(194)。在乌干达的一项涉及艾滋病毒阳性男性女性伴侣的RCT中,发现尽管接受了使用避孕套的咨询,但61%的性活跃参与者根本没有使用它们,20%的人不一致地使用它们,只有20% %总是使用它们(129)。在这项为期两年的随机对照试验的每次随访中,大多数人都没有使用安全套。

这些研究表明,有关安全套预防性病的有效性的证据是混杂的。避孕套是性传播感染预防工具箱的重要组成部分,但要有效,它们需要在一生中正确和一致地使用。相比之下,MC是一次性程序,每次男性进行性交时都不需要采取行动。当MC和避孕套都到位时,保护力更高(195)。问题是,要确保在最脆弱的人群中使用安全套是非常困难的。

艾滋病预防的暴露前预防(PrEP)

具有抗逆转录病毒药物的PrEP已被证明在研究环境中非常有效,并且正在几个国家推广。为可能数十年提供PrEP的成本和卫生系统的影响带来了挑战。 2017年,全球共有3690万人感染艾滋病毒,2170万人接受抗逆转录病毒治疗,180万人新感染艾滋病毒(196)。此外,尝试开发一种供女性使用的杀菌剂已经不成功(197-206)。

疫苗接种

针对STI的唯一疫苗是HPV。从2007年开始,针对HPV 16和18的预防性疫苗(约占70%的宫颈癌)以及四价疫苗的低风险HPV 6和11的预防性疫苗已经可用于高中初期的女孩或者与未上学的女孩相同的年龄(207)。这不仅降低了女性疫苗型HPV的流行率,而且女性疫苗接种计划具有流动的群体免疫效应,可减少男性HPV感染(208)。 2013年,该计划扩展到同龄男孩,预计将进一步减少两性中的HPV16和18感染。一项系统评价发现,在澳大利亚,最早接种女孩的国家之一(使用四价HPV疫苗),18岁和18岁女性的HPV 16型和18型减少了76-80%(不是100%)。 -24岁,美国和欧洲国家的减少量较少(207)。

在2007年的美国,在接种疫苗之前,HPV16是第六种最常见的高危HPV型,HPV18是第10位(209)。 HPV疫苗接种前37种HPV基因型的美国人群流行率基线估计总体为27%,20岁时达到最大值52%(210)。 HPV16的患病率在年龄组≤20,21-29和≥30岁时分别为9.6%,6.5%和1.8%(210)。 HPV16和/或HPV18患病率在各个年龄组中分别为12%,8.3%和2.4%(210)。这两种HPV类型存在于54.5%的高度鳞状上皮内病变中。模型表明,80%的女孩接种疫苗应使高危HPV患病率降低55%(211)。目前仅荷兰女孩接种疫苗的覆盖率为60%,与未接种疫苗的初次筛查相比,估计可使宫颈癌和死亡人数减少35%(212)。

在许多国家,生殖器HPV感染发生在较年轻的年龄。在HPV疫苗时代之前的英国,5%的14岁以下女孩患有HPV抗体,表明目前或之前的感染(213)。到16岁时,感染比例为12%,18岁时为20%,到24岁时为45%,之后随后减少(213)。致癌HPV16是最常见的类型。在美国,7%的12-19岁女孩患有HPV16抗体,20-29岁患者的抗体增加到25%(214)。发达国家青少年的其他性传播感染率也在上升。

通过疫苗接种从人群中消除HPV16和18可能需要数十年。在人群水平上,有人提出疫苗中未包括的其他致癌HPV类型可能会接管并取代这两种类型的HPV(210,215,216)。现在有证据证明这种情况正在发生。在澳大利亚为女孩推出HPV疫苗接种计划8年后,尽管HPV16和HPV18在异性恋男性中的患病率从13%降至3%(P <0.0001),但总体HPV基因型没有减少,且非流行疫苗靶向基因型从16%显著增加到22%(P <0.0001)(208)。美国一项研究发现接种疫苗4年后接种疫苗的年轻女性中,非疫苗类型的HPV从61%增加到76%(P <0.0001)(217)。此外,疫苗接种伴随着澳大利亚20-24岁(37.6%对47.7%)和25-29岁(45.2%对58.7%)女性参与宫颈筛查项目的比例下降(218 )。

疫苗接种的益处的长期持久性存在不确定性。引入一种非HPV疫苗,可以预防其他高风险类型31,33,45,52和58(意味着约90%的覆盖率),将可预防的HPV相关宫颈癌的百分比从66.2%提高到80.9% ,假设100%的覆盖率和功效(219)。对保护范围,依从性和长期免疫力的关注仍然存在。疫苗接种对外阴上皮瘤形成的影响要小得多(220),仅有一半的病例存在致癌HPV类型。由于HPV疫苗不能完全保护,因此需要继续进行宫颈癌筛查(221)。

虽然一些国家的HPV疫苗接种计划取得了成功,例如,由于其国家HPV疫苗接种计划(222),澳大利亚有望在20年内“消除”宫颈癌,但参与疫苗接种计划已受到阻碍保守派和宗教团体错误地声称在高中初期接种女儿会导致滥交的增加。加拿大和美国的研究发现,在年轻的青春期女孩中,HPV疫苗对性风险行为没有影响(223),并且对性活动相关结果没有显著影响(223)。尽管如此,美国对年轻青少年常规HPV疫苗接种的父母支持率很低(224)。另一个障碍是新闻媒体和互联网上强有力的反免疫游说团体的骚扰。所吹捧的大多数不良事件与疫苗无关,并且可以通过纯粹的巧合在任何大规模疫苗接种计划中看到。例如,Gullain-Barre综合征被认为是HPV疫苗的副作用,尽管HPV疫苗后,这种病症的患病率(0.06%)很低,并且不高于其他疫苗(225)。

虽然预防性HPV疫苗可以降低宫颈癌的发病率和死亡率,但它们并未涵盖全系列的致癌HPV类型。相比之下,MC部分保护免受所有致癌HPV类型的影响(106)。

总之,该数据支持个人和公共卫生措施的组合,应该提倡STI和生殖器癌症预防 - 在这里,MC,疫苗接种和安全套的使用应被视为协同工作。 MC和疫苗接种最好在性行为开始前进行(226),并在性活动开始后鼓励使用安全套。

女性中MC的可接受性

对来自9个撒哈拉以南非洲国家的13项研究的回顾发现,69%的女性(47-79%)偏爱其伴侣MC(227)。此外,81%(70-90%)的女性愿意让儿子接受割礼。南非的一项研究发现,女性对决定有很大影响,经常为男友或丈夫安排MC的预约(228)。 2005年南非RCT的作者提出了女性意识到MC对鼓励男性进行包皮环切术具有保护作用的重要作用(64)。特别是在艾滋病毒感染率高的地区,大多数未割包皮的男性都希望进行手术,一般来说,这些地区的女性比例更高,更愿意接受割礼的伴侣(229)。在非洲第一次VMMC推广计划中对MC的兴趣部分是由于女性对受割礼的伴侣的偏好(168)。在博茨瓦纳,92%的新生儿母亲希望他们的儿子在临床环境中接受包皮环切手术,85%的人表示父亲必须参与决定(230)。

在南非奥兰治农场的RCT环境中,女性对割礼伴侣的偏好从2007年的64.4%(n = 1,258)增加到2012年的73.7%(n = 2,583)(231)。在此期间,男孩的包皮环切术优先从80.4%增加到95.8%。在2,581名与接受过割礼和未割礼的男性发生性关系的女性中,55.8%认为受割礼的男子更容易使用安全套,20.5%不同意,23.1%不知道。有人建议MC,“可以迅速纳入大多数男性未受割礼的国家的国家计划”......正如在韩国,MC从50年前的几乎为零上升到今天的85%(232)。

数学模型预测,在艾滋病病毒感染率较高的非洲国家,在10%的MC摄取量下,男性和女性的艾滋病病毒感染率将降低45-67%(233)。吸收50%后,艾滋病毒将减少25-41%(233)。进一步的模拟预测,对于60%的疗效,19次割礼可以防止两种性别的艾滋病毒感染,每次感染避免成本为1,269美元(234)。

在撒哈拉以南非洲国家,青少年女性在说服年轻男性参与VMMC计划,支持他们参与的决定以及在伤口愈合过程中提供支持方面发挥了作用(235,236)。他们利用他们的浪漫关系或性别潜力作为杠杆点(235,236)。他们认为VMMC对双方的性健康有益,并且认为阴茎包皮的男性更有吸引力(235)。改善阴茎卫生和增加性快感是其他原因(236)。在男性伴侣接受包皮环切术后,女性没有表现出风险补偿行为(例如无保护性行为或更多伴侣)(237)。

限制

MC和女性性传播感染的文化差异可能会限制观察性研究数据的解释。 RCT可以克服这些限制。虽然RCT数据证实男性伴侣包皮环切术降低了女性HPV,阴道毛滴虫,细菌性阴道病和可能的生殖器溃疡病的风险,但没有关于HSV-2,沙眼衣原体,淋病奈瑟菌,梅毒螺旋体,生殖器支原体的RCT数据。女性,念珠菌和排尿困难。宫颈癌的RCT数据也缺乏,尽管这样的试验需要很多年,并且鉴于RCT数据显示割礼男性的女性伴侣的HPV风险降低,这可能被认为是不道德的。

未来的研究方向

在美国,成人口咽癌的HPV患病率从1984 - 1989年的16.3%显著增加到2000 - 2004年的71.7%(238)。据预测,2018年美国将记录49,750例新诊断的口咽癌,5年生存率为57%(239)。在口交期间HPV可以传播到口腔(240)。一项大型跨国研究发现,HPV参与全球约20%的口咽癌,MC患病率较高的国家患病率较高(241)。由于未割包皮的男性更容易感染HPV,因此与未割包皮的男性进行口交可能会增加感染和口咽癌的风险。然而,没有研究研究MC可能与口咽癌风险增加有关的程度。这些研究是必要的。

男性HPV感染与女性肛门癌风险增加有关(242),可能是直接通过肛门性接触,也可能通过HPV从子宫颈阴道位置或其他肛门生殖器部位间接传播。

在乳腺肿瘤中发现了高风险的HPV基因型(243,244),并且可以与宫颈癌女性的子宫颈相匹配(245,246)。这表明在性活动期间可能的HPV传播是某些乳腺肿瘤的原因(247)。为了支持这一点,HPV阳性乳腺癌患者明显比HPV阴性乳腺癌患者年轻,与年轻女性中性感获得性HPV感染的风险相关(248)。 HPV感染的鳞状上皮细胞(koilocytes)已在乳腺皮肤以及导管原位癌和浸润性导管癌的小叶中发现(249,250)。此外,在宫颈癌患者的血液中发现了HPV(251)。澳大利亚一项针对献血者的研究记录了附着于外周血单核细胞的HPV,这表明血液可能代表病毒储库和潜在的新传播途径(252)。还针对小鼠乳腺肿瘤病毒(MMTV)和爱泼斯坦 - 巴尔病毒(EBV)(244)引用了乳腺癌的病毒病因学。

一项荟萃分析发现HPV感染与男性和女性肺癌的显著相关性 - HPV16和HPV18共同显示肺鳞状细胞癌的风险高出9.8倍(253)。在分析的9项研究中缺乏关于烟草消费的数据,排除了对该风险因素的调整。

需要更多的研究来确定HPV在这些其他癌症的病因学中的作用,以及MC是否可以降低女性患者的风险。

结论

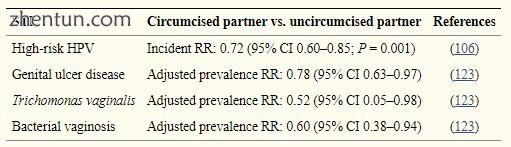

迄今为止对科学证据的系统评价确定MC是减少全球性传播感染对女性负担的潜在有力工具。本综述记录了MC对女性不同性传播感染的一系列有效性。根据随机对照试验的最高质量证据,可以得出结论,MC降低了女性致癌HPV基因型,宫颈癌,阴道毛滴虫,细菌性阴道病和可能的生殖器溃疡病的风险(表2)。对于女性中的其他性传播感染,关于MC的证据是可变的或消极的。

表2

针对性传播感染的RCT结果,MC保护女性免受伤害。

由于MC是一种高效,负担得起且可行的男性性传播感染预防工具,因此男性中一些性传播感染的人口流行率降低将降低女性性传播感染风险。美国疾病预防控制中心在其2018年的政策中认可了MC对女性的益处,这得益于详细审查(58)。有必要在艾滋病毒预防项目之外更广泛地扩大MC,同时增加对提高公众对其保护能力认识的努力的投入。有效的性传播感染预防需要结合公共卫生措施。

缺乏MC显然是全球宫颈癌流行的重要危险因素。无论是MC的公共卫生政策发生变化还是非割礼文化的移民增加,MC患病率下降的国家都可能会出现女性宫颈癌发病率增加的情况。 HPV疫苗接种计划可以部分改善这种增加。

男性可以在任何年龄接受割礼。最大限度的终生保护,不良事件的最小风险,成本考虑,速度,更快的愈合,最佳的美容效果和便利性适用于在婴儿早期进行的MC(254)。在2012年的政策建议中,美国儿科学会建议父母应该以无偏见的方式获得科学证据,并且可以自由地同意或拒绝让儿子接受割礼(255)。

在男性和男性的MC决定方面,女性可以拥有相当大的权力。他们可以影响婴儿早期或晚年对儿子(254),兄弟,其他男性家庭成员和朋友(256)的选择。此外,他们可以选择接受割礼的性伴侣或鼓励未受割礼的伴侣接受手术(256)。这样做有助于减少从婴儿期到老年期的男性中的性传播感染和一生的各种医疗问题,并有助于降低女性患某些性传播感染和宫颈癌的风险。

MC应被视为降低STI风险的一揽子措施的关键组成部分,每个组成部分协同工作。例如,在性初次登场前交付的MC和HPV疫苗将产生最大效果(226)。包括HPV疫苗接种和MC在内的公共卫生建议,以及其他已知的可降低STI风险的措施,如避孕套,性伴侣减少和PreP,特别是在高危HIV环境中,都在科学证据中得到了很好的巩固。

参考

1. World Health Organization Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) (2018). Available online at: http://www.who.int/news-room/fac ... smitted-infections-(stis) (Accessed August 15, 2018).

2. Casper C, Crane H, Menon M, Money D. HIV/AIDS comorbidities: impact on cancer, noncommunicable diseases, and reproductive health. In: Holmes KK, Bertozzi S, Bloom BR, Jha P, editors. , editors. Major Infectious Diseases. Washington, DC: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; (2017).

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention STDs in Women and Infants. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance 2017 (2017). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/womenandinf.htm (Accessed September 2, 2018).

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention New CDC Analysis Shows Steep and Sustained Increases in STDs in Recent Years (2018). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/news ... ion-conference.html (Accessed August 29, 2018).

5. Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis. (2010) 202:1789–99. 10.1086/657321 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2015 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines (2015). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/hpv.htm (Accessed August 21, 2018).

7. Patel EU, Gaydos CA, Packman ZR, Quinn TC, Tobian AAR. Prevalence and correlates of Trichomonas vaginalis infection among men and women in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. (2018) 67:211–7. 10.1093/cid/ciy079 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Peto J. Cancer epidemiology in the last century and the next decade. Nature (2001) 411:390–5. 10.1038/35077256 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Walboomers J, Meijer C. Do HPV-negative cervical carcinomas exist? J Pathol. (1997) 181:253–4. [PubMed]

10. Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, et al. . Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer. J Pathol. (1999) 189:12–9. [PubMed]

11. Bosch FX, Lorincz A, Munoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol. (2002) 55:244–65. 10.1136/jcp.55.4.244 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Valenti G, Vitale SG, Tropea A, Biondi A, Lagana AS. Tumor markers of uterine cervical cancer: a new scenario to guide surgical practice? Updates Surg. (2017) 69:441–9. 10.1007/s13304-017-0491-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Vitale SG, Valenti G, Rapisarda AMC, Cali I, Marilli I, Zigarelli M, et al. . P16INK4a as a progression/regression tumour marker in LSIL cervix lesions: our clinical experience. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. (2016) 37:685–8. 10.12892/ejgo3240.2016 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Cook DA, Krajden M, Brentnall AR, Gondara L, Chan T, Law JH, et al. . Evaluation of a validated methylation triage signature for human papillomavirus positive women in the HPV FOCAL cervical cancer screening trial. Int J Cancer. (2018). 10.1002/ijc.31976. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Rossetti D, Vitale SG, Tropea A, Biondi A, Lagana AS. New procedures for the identification of sentinel lymph node: shaping the horizon of future management in early stage uterine cervical cancer. Updates Surg. (2017) 69:383–8. 10.1007/s13304-017-0456-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Vitale SG, Capriglione S, Zito G, Lopez S, Gulino FA, Di Guardo F, et al. . Management of endometrial, ovarian and cervical cancer in the elderly: current approach to a challenging condition. Arch Gynecol Obstet. (2018). 10.1007/s00404-018-5006-z. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, Brenner H, et al. . Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. (2017) 3:524–48. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5688 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. World Health Organization . Cervical Cancer (2018). Available online at: http://www.who.int/cancer/preven ... cervical-cancer/en/ (Accessed September 3, 2018).

19. American Cancer Society Cancer Facts & Figures 2018 (2018). Available from URL: https://www.cancer.org/research/ ... s-figures-2018.html (Accessed July 18, 2018).

20. American Cancer Society The Global Economic Cost of Cancer (2015). Available online at: http://phrma-docs.phrma.org/site ... ic_impact_study.pdf (Accessed December 8, 2018).

21. de Martel C, Plummer M, Vignat J, Franceschi S. Worldwide burden of cancer attributable to HPV by site, country and HPV type. Int J Cancer (2017) 141:664–70. 10.1002/ijc.30716 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Jemal A, Simard EP, Dorell C, Noone AM, Markowitz LE, Kohler B, et al. . Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus(HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2013) 105:175–201. 10.1093/jnci/djs491 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Looker KJ, Magaret AS, Turner KM, Vickerman P, Gottlieb SL, Newman LM. Global estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 2 infections in 2012. PLoS ONE (2015) 10:e114989 10.1371/journal.pone.0114989 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Peipert JF. Genital chlamydial infections. N Engl J Med. (2003) 349:2424–30. 10.1056/NEJMcp030542 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Chlamydia. 2016 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance (2016). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats16/chlamydia.htm (Accessed August 21, 2018).

26. Madeleine MM, Anttila T, Schwartz SM, Saikku P, Leinonen M, Carter JJ, et al. . Risk of cervical cancer associated with Chlamydia trachomatis antibodies by histology, HPV type and HPV cofactors. Int J Cancer (2007) 120:650–5. 10.1002/ijc.22325 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Trabert B, Waterboer T, Idahl A, Brenner N, Brinton LA, Butt J, et al. . Antibodies against Chlamydia trachomatis and ovarian cancer risk in two independent populations. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2018). 10.1093/jnci/djy084. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Wi T, Lahra MM, Ndowa F, Bala M, Dillon JR, Ramon-Pardo P, et al. . Antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Global surveillance and a call for international collaborative action. PLoS Med. (2017) 14:e1002344. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002344 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. McIver CJ, Rismanto N, Smith C, Naing ZW, Rayner B, Lusk MJ, et al. . Multiplex PCR testing detection of higher-than-expected rates of cervical mycoplasma, ureaplasma, and trichomonas and viral agent infections in sexually active Australian women. J Clin Microbiol. (2009) 47:1358–63. 10.1128/JCM.01873-08 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Fiori PL, Diaz N, Cocco AR, Rappelli P, Dessi D. Association of Trichomonas vaginalis with its symbiont Mycoplasma hominis synergistically upregulates the in vitro proinflammatory response of human monocytes. Sex Transm Infect. (2013) 89:449–54. 10.1136/sextrans-2012-051006 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Korenromp EL, Mahiane SG, Nagelkerke N, Taylor MM, Williams R, Chico RM, et al. . Syphilis prevalence trends in adult women in 132 countries - estimations using the Spectrum Sexually Transmitted Infections model. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:11503. 10.1038/s41598-018-29805-9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Low N, Broutet N, Adu-Sarkodie Y, Barton P, Hossain M, Hawkes S. Global control of sexually transmitted infections. Lancet (2006) 368:2001–16. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69482-8 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV Surveillance Report 2018 (2016). https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/index.html (Accessed July 16, 2018).

34. Kirby Institute HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexually Transmissable Infections in Australia. Annual Surveillance Report 2018 (2018). Available from URL: https://kirby.unsw.edu.au/report ... annual-surveillance (Accessed December 12, 2018).

35. Potts M, Halperin DT, Kirby D, Swidler A, Marseille E, Klausner JD, et al. . Reassessing HIV prevention. Science (2008) 320:749–50. 10.1126/science.1153843 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Fonck K, Kidula N, Kirrui P, Ndinya-Achola J, Bwayo J, Claeys P, et al. . Pattern of sexually transmitted diseases and risk factors among women attending an STD referral clinic in Nairobi, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. (2000) 27:417–23. 10.1097/00007435-200008000-00007 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Murta EF, Silva AO, Silva EA, Adad SJ. Frequency of infectious agents for vaginitis in non- and hysterectomized women. Arch Gynecol Obstetr. (2005) 273:152–6. 10.1007/s00404-005-0023-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Bitew A, Abebaw Y, Bekele D, Mihret A. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis and associated risk factors among women complaining of genital tract infection. Int J Microbiol. (2017) 2017: 4919404. 10.1155/2017/4919404 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Fethers KA, Fairley CK, Hocking JS, Gurrin LC, Bradshaw CS. Sexual risk factors and bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. (2008) 47:1426–35. 10.1086/592974 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Marconi C, Duarte MT, Silva DC, Silva MG. Prevalence of and risk factors for bacterial vaginosis among women of reproductive age attending cervical screening in southeastern Brazil. Int J Gynaecol Obstetr. (2015) 131:137–41. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.05.016 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Gillet E, Meys JF, Verstraelen H, Verhelst R, De Sutter P, Temmerman M, et al. . Association between bacterial vaginosis and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE (2012) 7:e45201. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045201 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Harbour R, Miller J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ (2001) 323:334–6. 10.1136/bmj.323.7308.334 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Cathcart P, Nuttall M, van der Meulen J, Emberton M, Kenny SE. Trends in paediatric circumcision and its complications in England between 1997 and 2003. Br J Surg. (2006) 93:885–90. 10.1002/bjs.5369 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Morris BJ, Bailis SA, Wiswell TE. Circumcision rates in the United States: rising or falling? What effect might the new affirmative pediatric policy statement have? Mayo Clin Proc. (2014) 89:677–86. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.01.001 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Morris BJ, Wamai RG. Biological basis for the protective effect conferred by male circumcision against HIV infection. Int J STD AIDS (2012) 23:153–9. 10.1258/ijsa.2011.011228 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Lemos MP, Lama JR, Karuna ST, Fong Y, Montano SM, Ganoza C, et al. . The inner foreskin of healthy males at risk of HIV infection harbors epithelial CD4+ CCR5+ cells and has features of an inflamed epidermal barrier. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e108954. 10.1371/journal.pone.0108954 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Ben Chaim J, Livne PM, Binyamini J, Hardak B, Ben-Meir D, Mor Y. Complications of circumcision in Israel: a one year multicenter survey. Isr Med Assoc J. (2005) 7:368–70. [PubMed]

48. American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Male circumcision. Pediatrics (2012) 130:e756–85. 10.1542/peds.2012-1990 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. El Bcheraoui C, Zhang X, Cooper CS, Rose CE, Kilmarx PH, Chen RT. Rates of adverse events associated with male circumcision in US medical settings, 2001 to 2010. JAMA Pediatr. (2014) 168:625–34. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.5414 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Hung YC, Chang DC, Westfal ML, Marks IH, Masiakos PT, Kelleher CM. A longitudinal population analysis of cumulative risks of circumcision. J Surg Res. (2019) 233:111–7. 10.1016/j.jss.2018.07.069 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Morris BJ, Kennedy SE, Wodak AD, Mindel A, Golovsky D, Schrieber L, et al. . Early infant male circumcision: systematic review, risk-benefit analysis, and progress in policy. World J Clin Pediatr. (2017) 6:89–102. 10.5409/wjcp.v6.i1.89 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Hayashi Y, Kohri K. Circumcision related to urinary tract infections, sexually transmitted infections, human immunodeficiency virus infections, and penile and cervical cancer. Int J Urol. (2013) 20:769–75. 10.1111/iju.12154 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Morris BJ, Wiswell TE. Circumcision and lifetime risk of urinary tract infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. (2013) 189:2118–24. 10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.114 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Weiss HA, Thomas SL, Munabi SK, Hayes RJ. Male circumcision and risk of syphilis, chancroid, and genital herpes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. (2006) 82:101–9. 10.1136/sti.2005.017442 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Morris BJ, Castellsague X. The role of circumcision in preventing STIs. In: Gross GE, Tyring SK, editors. , editors. Sexually Transmitted Infections and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; (2011). p. 715–39. 10.1007/978-3-642-14663-3_54 [CrossRef]

56. Morris BJ, Hankins CA, Tobian AA, Krieger JN, Klausner JD. Does male circumcision protect against sexually transmitted infections? Arguments and meta-analyses to the contrary fail to withstand scrutiny. ISRN Urol. (2014) 2014:684706. 10.1155/2014/684706 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Tobian AAR, Kacker S, Quinn TC. Male circumcision: a globally relevant but under-utilized method for the prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Annu Rev Med. (2014) 65:293–306. 10.1146/annurev-med-092412-090539 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Male Circumcision (2018). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/male-circumcision.html (Accessed October 4, 2018).

59. Bongaarts J, Peining P, Way P, Conont F. The relationship between male circumcision and HIV infection in African populations. AIDS (1989) 3:373–7. 10.1097/00002030-198906000-00006 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Moses S, Bradley JE, Nagelkerke NJ, Ronald AR, Ndinya Achola JO, Plummer FA. Geographical patterns of male circumcision practices in Africa: association with HIV seroprevalance. Int J Epidemiol. (1990) 19:693–7. 10.1093/ije/19.3.693 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Gray RH, Kiwanuka N, Quinn TC, Sewankambo NK, Serwadda D, Mangen FW, et al. . Male circumcision and HIV aquisition and transmission: cohort studies in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS (2000) 14:2371–81. 10.1097/00002030-200010200-00019 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Auvert B, Buvé A, Lagarde E, Kahindo M, Chege J, Rutenberg N, et al. . Male circumcision and HIV infection in four cities in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS (2001) 15:S31–40. 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00004 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Gebremedhin S. Assessment of the protective effect of male circumcision from HIV infection and sexually transmitted diseases: evidence from 18 demographic and health surveys in sub-Saharan Africa. Afr J Reprod Health (2010) 14:105–13. 10.1080/17290376.2011.9724979 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. (2005) 2:e298. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, et al. . Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (2007) 369:643–56. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, et al. . Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet (2007) 369:657–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Weiss HA, Halperin D, Bailey RC, Hayes RJ, Schmid G, Hankins CA. Male circumcision for HIV prevention: from evidence to action? AIDS (2008) 22:567–74. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f3f406 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks JJ, Volmink J. Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2009) CD003362. 10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. World Health Organization and Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS Male Circumcision: Global Trends and Determinants of Prevalence, Safety and Acceptability (2007). Available online at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241596169_eng.pdf (Accessed Febuary 17, 2018).

70. PEPFAR U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, Fact Sheet. PEPFAR Latest Global Results (2018). Available online at: https://www.pepfar.gov/documents/organization/287811.pdf (Accessed December 15, 2018).

71. Fauci AS, Eisinger RW. PEPFAR - 15 years and counting the lives saved. N Engl J Med. (2018) 378:314–6. 10.1056/NEJMp1714773 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Circumcision policy statement. Pediatrics (2012) 130:585–6. 10.1542/peds.2012-1989 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Grund JM, Bryant TS, Jackson I, Curran K, Bock N, Toledo C, et al. . Association between male circumcision and women's biomedical health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health (2017) 5:e1113–22. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30369-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Kong X, Kigozi G, Ssekasanvu J, Nalugoda F, Nakigozi G, Ndyanabo A, et al. . Association of medical male circumcision and antiretroviral therapy scale-up with community HIV incidence in Rakai, Uganda. JAMA (2016) 316:182–90. 10.1001/jama.2016.7292 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Auvert B, Taljaard D, Rech D, Lissouba P, Singh B, Bouscaillou J, et al. . Association of the ANRS-12126 male circumcision project with HIV levels among men in a South African township: evaluation of effectiveness using cross-sectional surveys. PLoS Med. (2013) 10: e1001509. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001509 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Grabowski MK, Serwadda DM, Gray RH, Nakigozi G, Kigozi G, Kagaayi J, et al. . HIV prevention efforts and incidence of HIV in Uganda. N Engl J Med. (2017) 377:2154–66. 10.1056/NEJMoa1702150 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. McGillen JB, Stover J, Klein DJ, Xaba S, Ncube G, Mhangara M, et al. . The emerging health impact of voluntary medical male circumcision in Zimbabwe: an evaluation using three epidemiological models. PLoS ONE (2018) 13:e0199453. 10.1371/journal.pone.0199453 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Borgdorff MW, Kwaro D, Obor D, Otieno G, Kamire V, Odongo F, et al. . HIV incidence in western Kenya during scale-up of antiretroviral therapy and voluntary medical male circumcision: a population-based cohort analysis. Lancet HIV (2018) 5:e241–9. 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30025-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Cuadros DF, Branscum AJ, Miller FD, Awad SF, Abu-Raddad LJ. Are geographical “cold spots” of male circumcision driving differential HIV dynamics in Tanzania? Front Public Health (2015) 3:218. 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00218 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Ibrahim E, Asghari S. Commentary: Are geographical “cold spots” of male circumcision driving differential HIV dynamics in Tanzania? Front Public Health (2016) 4:46. 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00046 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Quinn TC, Wawer MJ, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Li C, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. . Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. N Engl J Med. (2000) 342:921–9. 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Bosch FX, Albero G, Castellsagué X. Male circumcision, human papillomavirus and cervical cancer: from evidence to intervention. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care (2009) 35:5–7. 10.1783/147118909787072270 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Castellsague X, Bosch FX, Munoz N, Meijer CJ, Shah KV, de Sanjose S, et al. . Male circumcision, penile human papillomavirus infection, and cervical cancer in female partners. N Engl J Med. (2002) 346:1105–12. 10.1056/NEJMoa011688 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Drain PK, Halperin DT, Hughes JP, Klausner JD, Bailey RC. Male circumcision, religion, and infectious diseases: an ecologic analysis of 118 developing countries. BMC Infect Dis. (2006) 6:172. 10.1186/1471-2334-6-172 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Boyd JT, Doll R. A study of the aetiology of carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Br J Cancer (1964) 13:419–34. 10.1038/bjc.1964.49 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Brinton LA, Reeves WC, Brenes MM, Herrero R, Gaitan E, Tenorio F, et al. . The male factor in the etiology of cervical cancer among sexually monogamous women. Int J Cancer (1989) 44:199–203. 10.1002/ijc.2910440202 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Kjaer SK, de Villiers EM, Dahl C, Engholm G, Bock JE, Vestergaard BF, et al. . Case-control study of risk factors for cervical neoplasia in Denmark. I: role of the “male factor” in women with one lifetime sexual partner. Int J Cancer (1991) 48:39–44. 10.1002/ijc.2910480108 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Aung MT, Soe MY, Mya WW. Study on risk factors for cervical carcinoma at Central Womens Hospital, Yangon, Myanmar. In: BJOG 10th International Scientific Congress of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, RCOG 2012. Kuching: (2012). p. 124.

89. Kim J, Kim BK, Lee CH, Seo SS, Park SY, Roh JW. Human papillomavirus genotypes and cofactors causing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer in Korean women. Int J Gynecol Cancer (2012) 22:1570–6. 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31826aa5f9 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Braithwaite J. Excess salt in the diet a probable factor in the causation of cancer. Lancet (1901) 158:1578–80. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)44674-X [CrossRef]

91. Plaut A, Kohn-Speyer AC. The carcinogenic action of smegma. Science (1947) 105:391–2. 10.1126/science.105.2728.391-a [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Pratt-Thomas HR, Heins HC, Latham E, Dennis EJ, McIver FA. Carcinogenic effect of human smegma: an experimental study. Cancer (1956) 9:671–80. [PubMed]

93. Heins HC, Jr, Dennis EJ. The possible role of smegma in carcinoma of the cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (1958) 76:726–33. 10.1016/0002-9378(58)90004-8 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Reddy DG, Baruah IK. Carcinogenic action of human smegma. Arch Pathol. (1963) 75:414. [PubMed]

95. Terris M, Wilson F, Nelson JH, Jr. Relation of circumcision to cancer of the cervix. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (1973) 117:1056–66. 10.1016/0002-9378(73)90754-0 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Agarwal SS, Sehgal A, Sardana S, Kumar A, Luthra UK. Role of male behaviour in cervical carcinogenesis among women with one lifetime sexual partner. Cancer (1993) 72:1666–9. [PubMed]

97. Dhar GM, Shah GN, Naheed B, Hafiza. Epidemiological trend in the distribution of cancer in Kashmir Valley. J Epidemiol Community Health (1993) 47:290–2. 10.1136/jech.47.4.290 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Gajalakshmi CK, Shanta V. Association between cervical and penile cancers in Madras, India. Acta Oncol. (1993) 32:617–20. 10.3109/02841869309092439 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Svare EI, Kjaer SK, Worm AM, Osterlind A, Meijer CJ, van den Brule AJ. Risk factors for genital HPV DNA in men resemble those found in women: a study of male attendees at a Danish STD clinic. Sex Transm Infect. (2002) 78:215–8. 10.1136/sti.78.3.215 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Yasmeen J, Qurieshi MA, Manzoor NA, Asiya W, Ahmad SZ. Community-based screening of cervical cancer in a low prevalence area of India: a cross sectional study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. (2010) 11:231–4. [PubMed]

101. Al-Awadhi R, Chehadeh W, Kapila K. Prevalence of human papillomavirus among women with normal cervical cytology in Kuwait. J Med Virol. (2011) 83:453–60. 10.1002/jmv.21981 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Shavit O, Roura E, Barchana M, Diaz M, Bornstein J. Burden of human papillomavirus infection and related diseases in Israel. Vaccine (2013) 31(Suppl. 8):I32–41. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.108 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Dajani YF, Maayta UM, Abu-Ghosh YR. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in Jordan: A ten year retrospective cytoepidemiologic study. Ann Saudi Med. (1995) 15:354–7. 10.5144/0256-4947.1995.354 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Soh J, Rositch AF, Koutsky L, Guthrie BL, Choi RY, Bosire RK, et al. . Individual and partner risk factors associated with abnormal cervical cytology among women in HIV-discordant relationships. Int J STD AIDS (2014) 25:315–24. 10.1177/0956462413504554 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Kolawole O, Olatunji K, Durowade K, Adeniyi A, Omokanye L. Prevalence, risk factors of human papillomavirus infection and papanicolaou smear pattern among women attending a tertiary health facility in south-west Nigeria. TAF Prev Med Bull. (2015) 14:453–9. 10.5455/pmb.1-1426429287 [CrossRef]

106. Wawer MJ, Tobian AAR, Kigozi G, Kong X, Gravitt PE, Serwadda D, et al. . Effect of circumcision of HIV-negative men on transmission of human papillomavirus to HIV-negative women: a randomised trial in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet (2011) 377:209–18. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61967-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Lei JH, Liu LR, Wei Q, Yan SB, Yang L, Song TR, et al. . Circumcision status and risk of HIV acquisition during heterosexual intercourse for both males and females: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE (2015) 10:e0125436. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125436 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Grabowski MK, Kong X, Gray RH, Serwadda D, Kigozi G, Gravitt PE, et al. . Partner human papillomavirus viral load and incident human papillomavirus detection in heterosexual couples. J Infect Dis. (2016) 213:948–56. 10.1093/infdis/jiv541 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Tobian AA, Kong X, Wawer MJ, Kigozi G, Gravitt PE, Serwadda D, et al. . Circumcision of HIV-infected men and transmission of human papillomavirus to female partners: analyses of data from a randomised trial in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet Infect Dis. (2011) 11:604–12. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70038-X [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Roura E, Iftner T, Vidart JA, Kjaer SK, Bosch FX, Munoz N, et al. . Predictors of human papillomavirus infection in women undergoing routine cervical cancer screening in Spain: the CLEOPATRE study. BMC Infect Dis. (2012) 12:145. 10.1186/1471-2334-12-145 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Obiri-Yeboah D, Akakpo PK, Mutocheluh M, Adjei-Danso E, Allornuvor G, Amoako-Sakyi D, et al. . Epidemiology of cervical human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL) among a cohort of HIV-infected and uninfected Ghanaian women. BMC Cancer (2017) 17:688. 10.1186/s12885-017-3682-x [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Senkomago V, Backes DM, Hudgens MG, Poole C, Meshnick SR, Agot K, et al. . Higher HPV16 and HPV18 penile viral loads are associated with decreased human papillomavirus clearance in uncircumcised Kenyan men. Sex Transm Dis. (2016) 43:572–8. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000500 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Davis MA, Gray RH, Grabowski MK, Serwadda D, Kigozi G, Gravitt PE, et al. . Male circumcision decreases high-risk human papillomavirus viral load in female partners: a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Int J Cancer (2013) 133:1247–52. 10.1002/ijc.28100 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Tobian AA, Kigozi G, Redd AD, Serwadda D, Kong X, Oliver A, et al. . Male circumcision and herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in female partners: a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. (2012) 205:486–90. 10.1093/infdis/jir767 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Mugo N, Dadabhai SS, Bunnell R, Williamson J, Bennett E, Baya I, et al. . Prevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection, human immunodeficiency virus/herpes simplex virus type 2 coinfection, and associated risk factors in a national, population-based survey in Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. (2011) 38:1059–66. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31822e60b6 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Cherpes TL, Meyne LA, Krohn MA, Hiller SL. Risk factors for infection with herpes simplex virus type 2: Role of smoking, douching, uncircumcised males, and vaginal flora. Sex Transm Dis. (2003) 30:405–10. 10.1097/00007435-200305000-00006 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Borkakoty B, Biswas D, Walia K, Mahanta J. Potential impact of spouse's circumcision on herpes simplex virus type 2 prevalence among antenatal women in five northeastern states of India. Int J Infect Dis. (2010) 14:e411 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.02.533 [CrossRef]

118. Mujugira A, Magaret AS, Baeten JM, Celum C, Lingappa J. Risk factors for HSV-2 infection among sexual partners of HSV-2/HIV-1 co-infected persons. BMC Res Notes (2011) 4:64. 10.1186/1756-0500-4-64 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Davis S, Toledo C, Lewis L, Cawood C, Bere A, Glenshaw M, et al. Association Between HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections and Partner Circumcision Among Women in uMgungundlovu District, South Africa: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of HIPSS Baseline Data. IAS2017 (2017). Available online at: http://programme.ias2017.org/Abstract/Abstract/2833 (Accessed August 8, 2018).

120. Mehta SD, Pradhan AK, Green SJ, Naqib A, Odoyo-June E, Gaydos CA, et al. . Microbial diversity of genital ulcers of HSV-2 seropositive women. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:15475. 10.1038/s41598-017-15554-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Brankin AE, Tobian AAR, Laeyendecker O, Suntoke TR, Kizza A, Mpoza B, et al. . Aetiology of genital ulcer disease in female partners of male participants in a circumcision trial in Uganda. Int J STD AIDS (2009) 20:650–1. 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009067 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Tobian AA, Gaydos C, Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Quinn N, et al. . Male circumcision and Mycoplasma genitalium infection in female partners: a randomised trial in Rakai, Uganda. Sex Transm Infect. (2014) 90:150–4. 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051293 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Nalugoda F, Watya S, et al. . The effects of male circumcision on female partners' genital tract symptoms and vaginal infections in a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (2009) 200:42 e1–7. 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.069 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Castellsague X, Peeling RW, Franceschi S, de Sanjose S, Smith JS, Albero G, et al. . Chlamydia trachomatis infection in female partners of circumcised and uncircumcised adult men. Am J Epidemiol. (2005) 162:907–16. 10.1093/aje/kwi284 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Turner AN, Morrison CS, Padian NS, Kaufman JS, Behets FM, Salata RA, et al. . Male circumcision and women's risk of incident chlamydial, gonococcal, and trichomonal infections. Sex Transm Dis. (2008) 35:689–95. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31816b1fcc [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Russell AN, Zheng X, O'Connell CM, Taylor BD, Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, et al. . Analysis of factors driving incident and ascending infection and the role of serum antibody in Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection. J Infect Dis. (2016) 213:523–31. 10.1093/infdis/jiv438 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Nayyar C, Chander R, Gupta P, Sherwal BL. Co-infection of human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted infections in circumcised and uncircumcised cases in India. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS (2014) 35:114–7. 10.4103/0253-7184.142405 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Moodley J, Naidoo S, Reddy T, Kelly C, Ramjee G. Awareness of Male Partner Circumcision on Women's Sexual and Reproductive Health. Durban: AIDS; (2016).

129. Wawer MJ, Makumbi F, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Watya S, Nalugoda F, et al. . Circumcision in HIV-infected men and its effect on HIV transmission to female partners in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (2009) 374:229–37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60998-3 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Pintye J, Baeten JM, Manhart LE, Celum C, Ronald A, Mugo N, et al. . Association between male circumcision and incidence of syphilis in men and women: a prospective study in HIV-1 serodiscordant heterosexual African couples. Lancet Glob Health (2014) 2:E664–71. 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70315-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

131. Lawi JD, Mirambo MM, Magoma M, Mushi MF, Jaka HM, Gumodoka B, et al. . Sero-conversion rate of Syphilis and HIV among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Tanzania: a need for re-screening at delivery. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth (2015) 15:3. 10.1186/s12884-015-0434-2 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

132. Chao A, Bulterys M, Musanganire F, Habimana P, Nawrocki P, Taylor E, et al. . Risk factors associated with prevalent HIV-1 infection among pregnant women in Rwanda. National University of Rwanda-Johns Hopkins University AIDS Research Team. Int J Epidemiol. (1994) 23:371–80. 10.1093/ije/23.2.371 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

133. Hunter DJ, Maggwa BN, Mati JK, Tukei PM, Mbugua S. Sexual behavior, sexually transmitted diseases, male circumcision and risk of HIV infection among women in Nairobi, Kenya. AIDS (1994) 8:93–9. 10.1097/00002030-199401000-00014 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

134. Kapiga SH, Lyamuya EF, Lwihula GK, Hunter DJ. The incidence of HIV infection among women using family planning methods in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS (1998) 12:75–84. 10.1097/00002030-199801000-00009 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

135. Turner AN, Morrison CS, Padian NS, Kaufman JS, Salata RA, Chipato T, et al. . Men's circumcision status and women's risk of HIV acquisition in Zimbabwe and Uganda. AIDS (2007) 21:1779–89. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32827b144c [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

136. Babalola S. Factors associated with HIV infection among sexually experienced adolescents in Africa: a pooled data analysis. Afr J AIDS Res. (2011) 10:403–14. 10.2989/16085906.2011.646655 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

137. Baeten JM, Donnell D, Kapiga SH, Ronald A, John-Stewart G, Inambao M, et al. . Male circumcision and risk of male-to-female HIV-1 transmission: a multinational prospective study in African HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. AIDS (2010) 24:737–44. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833616e0 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

138. Poulin M, Muula AS. An inquiry into the uneven distribution of women's HIV infection in rural Malawi. Demogr Res. (2011) 25:869–902. 10.4054/DemRes.2011.25.28 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

139. Hughes JP, Baeten JM, Lingappa JR, Magaret AS, Wald A, de Bruyn G, et al. . Determinants of per-coital-act HIV-1 infectivity among African HIV-1-serodiscordant couples. J Infect Dis. (2012) 205:358–65. 10.1093/infdis/jir747 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

140. Jean K, Lissouba P, Taljaard D, Taljaard R, Singh B, Bouscaillou J, et al. HIV incidence among women is associated with their partners' circumcision status in the township of Orange Farm (South Africa) where the male circumcision roll-out is ongoing (ANRS-12126). In: International AIDS Conference. Melbourne, VIC: (2014). Available online at: http://pag.aids2014.org/Abstracts.aspx?AID=11010 (Accessed August 8, 2018).

141. Auvert A, Lissouba P, Taljaard D, Peytavin G, Singh B, Puren A. Male circumcision: association with HIV prevalence knowledge and attitudes among women. In: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections 2014. Boston, MA: (2015).

142. Fatti G, Shaikh N, Jackson D, Goga A, Nachega JB, Eley B, et al. . Low HIV incidence in pregnant and postpartum women receiving a community-based combination HIV prevention intervention in a high HIV incidence setting in South Africa. PLoS ONE (2017) 12:e0181691. 10.1371/journal.pone.0181691 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

143. Allen S, Lindan C, Serufilira A, Van de Perre P, Rundle AC, Nsengumuremyi F, et al. . Human immunodeficiency virus infection in urban Rwanda. Demographic and behavioral correlates in a representative sample of childbearing women. JAMA (1991) 266:1657–63. 10.1001/jama.1991.03470120059033 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

144. Mapingure MP, Msuya S, Kurewa NE, Munjoma MW, Sam N, Chirenje MZ, et al. Sexual behaviour does not reflect HIV-1 prevalence differences: a comparison study of Zimbabwe and Tanzania. J Int AIDS Soc. (2010) 13:45 10.1186/1758-2652-13-45 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

145. Chemtob D, Op de Coul E, van Sighem A, Mor Z, Cazein F, Semaille C. Impact of Male Circumcision among heterosexual HIV cases: comparisons between three low HIV prevalence countries. Isr J Health Policy Res. (2015) 4:36. 10.1186/s13584-015-0033-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

146. Fox A, Noncon AA. Does Male Circumcision Indirectly Reduce Female HIV Risk? Evidence from Four Demographic Health Surveys. Durban: AIDS; (2016). Available online at: http://programme.aids2016.org/Abstract/Abstract/5170 (Accessed July 16, 2018).

147. Tobian AA, Gray RH, Quinn TC. Male circumcision for the prevention of acquisition and transmission of sexually transmitted infections: the case for neonatal circumcision. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. (2010) 164:78–84. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.232 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

148. Cherpes TL, Hillier SL, Meyn LA, Busch JL, Krohn MA. A delicate balance: risk factors for acquisition of bacterial vaginosis include sexual activity, absence of hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli, black race, and positive herpes simplex virus type 2 serology. Sex Transm Dis. (2008) 35:78–83. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318156a5d0 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

149. Zenilman JM, Fresia A, Berger B, McCormack WM. Bacterial vaginosis is not associated with circumcision status of the current male partner. Sex Transm Infect. (1999) 75:347–8. 10.1136/sti.75.5.347 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

150. Schwebke JR, Desmond R. Risk factors for bacterial vaginosis in women at high risk for sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. (2005) 32:654–8. 10.1097/01.olq.0000175396.10304.62 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

151. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

152. World Health Organization WHO Guidelines on the Management of Health Complications from Female Genital Mutilation (2016). Available online at: http://www.who.int/reproductiveh ... mplications-fgm/en/ (Accessed Septemeber 1, 2018).

153. Durst M, Gissmann L, Ikenberg H, zur Hausen H. A papillomavirus DNA from a cervical carcinoma and its prevalence in cancer biopsy samples from different geographic regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1983) 80:3812–5. 10.1073/pnas.80.12.3812 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

154. Barrasso R, De Brux J, Croissant O, Orth G. High prevalence of papillomavirus associated penile intraepithelial neoplasia in sexual partners of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. (1987) 317:916–23. 10.1056/NEJM198710083171502 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

155. Aynaud O, Ionesco M, Barrasso R. Penile intraepithelial neoplasia. Specific clinical features correlate with histologic and virologic findings. Cancer (1994) 74:1762–7. [PubMed]

156. Tobian AAR, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, Kigozi G, Gravitt PE, Laeyendecker O, et al. . Male circumcision for the prevention of HSV-2 and HPV infections and syphilis. N Engl J Med. (2009) 360:1298–309. 10.1056/NEJMoa0802556 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

157. Auvert B, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Cutler E, Nieuwoudt M, Lissouba P, Puren A, et al. . Effect of male circumcision on the prevalence of high-risk human papillomavirus in young men: results of a randomized controlled trial conducted in Orange Farm, South Africa. J Infect Dis. (2009) 199:14–9. 10.1086/595566 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

158. Gray RH, Serwadda D, Kong X, Makumbi F, Kigozi G, Gravitt PE, et al. . Male circumcision decreases acquisition and increases clearance of high-risk human papillomavirus in HIV-negative men: a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. (2010) 201:1455–62. 10.1086/652184 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

159. Backes DM, Bleeker MC, Meijer CJ, Hudgens MG, Agot K, Bailey RC, et al. . Male circumcision is associated with a lower prevalence of human papillomavirus-associated penile lesions among Kenyan men. Int J Cancer (2012) 130:1888–97. 10.1002/ijc.26196 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

160. Wilson LE, Gravitt P, Tobian AA, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Nalugoda F, et al. . Male circumcision reduces penile high-risk human papillomavirus viral load in a randomised clinical trial in Rakai, Uganda. Sex Transm Infect. (2013) 89:262–6. 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050633 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

161. Kjaer SK, Chackerian B, van den Brule AJ, Svare EI, Paull G, Walbomers JM, et al. . High-risk human papillomavirus is sexually transmitted: evidence from a follow-up study of virgins starting sexual activity (intercourse). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. (2001) 10:101–6. [PubMed]

162. Lei Y, Wan J, Pan LJ, Kan YJ. [Human papillomavirus infection correlates with redundant prepuce or phimosis in the patients'sexual partners in Nanjing urban area]. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue (2012) 18:876–80. [PubMed]

163. Waskett JH, Morris BJ, Weiss HA. Errors in meta-analysis by Van Howe. Int J STD AIDS (2009) 20:216–8. 10.1258/ijsa.2009.008126 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

164. Mehta SD, Moses S, Agot K, Parker C, Ndinya-Achola JO, Maclean I, et al. . Adult male circumcision does not reduce the risk of incident Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, or Trichomonas vaginalis infection: results from a randomized, controlled trial in Kenya. J Infect Dis. (2009) 200:370–8. 10.1086/600074 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

165. Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Taljaard D, Nieuwoudt M, Lissouba P, Puren A, Auvert B. Male circumcision and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Trichomonas vaginalis: observations in the aftermath of a randomised controlled trial for HIV prevention. Sex Transm Infect. (2009) 85:116–20. 10.1136/sti.2008.032334 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

166. Steen R. Eradicating chancroid. Bull World Health Organ (2001) 79:818–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

167. Lewis DA. Epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of Haemophilus ducreyi - a disappearing pathogen? Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. (2014) 12:687–96. 10.1586/14787210.2014.892414 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

168. Baeten JM, Celum C, Coates TJ. Male circumcision and HIV risks and benefits for women. Lancet (2009) 374:182–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61311-8 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

169. Weiss HA, Hankins CA, Dickson K. Male circumcision and risk of HIV infection in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. (2009) 9:669–77. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70235-X [PubMed] [CrossRef]

170. Reis Machado J, da Silva MV, Cavellani CL, dos Reis MA, Monteiro ML, Teixeira Vde P, et al. . Mucosal immunity in the female genital tract, HIV/AIDS. Biomed Res Int. (2014) 2014:350195. 10.1155/2014/350195 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

171. Talman A, Bolton S, Walson JL. Interactions between HIV/AIDS and the environment: toward a syndemic framework. Am J Public Health (2013) 103:253–61. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300924 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

172. Bull ME, Legard J, Tapia K, Sorensen B, Cohn SE, Garcia R, et al. . HIV-1 shedding from the female genital tract is associated with increased Th1 cytokines/chemokines that maintain tissue homeostasis and proportions of CD8+FOXP3+ T cells. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (2014) 67:357–64. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000336 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

173. Nsubuga P, Mugerwa R, Nsibambi J, Sewankambo N, Katabira E, Berkley S. The association of genital ulcer disease and HIV infection at a dermatology-STD clinic in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. (1990) 3:1002–5. [PubMed]

174. Watson-Jones D, Weiss HA, Rusizoka M, Changalucha J, Baisley K, Mugeye K, et al. . Effect of herpes simplex suppression on incidence of HIV among women in Tanzania. N Engl J Med. (2008) 358:1560–71. 10.1056/NEJMoa0800260 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

175. Chersich MF, Rees HV. Vulnerability of women in southern Africa to infection with HIV: biological determinants and priority health sector interventions. AIDS (2008) 22:S27–40. 10.1097/01.aids.0000341775.94123.75 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

176. UNAIDS/WHO/SACEMA Expert Group on Modelling the Impact and Cost of Male Circumcision for HIV Prevention. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in high HIV prevalence settings: what can mathematical modelling contribute to informed decision making? PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000109 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000109 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

177. Kagumire R. Ugandan effort to constrain HIV spread hampered by systemic and cultural obstacles to male circumcision. Can Med Assoc J. (2008) 179:1119–20. 10.1503/cmaj.081761 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

178. Zabor EC, Klebanoff M, Yu K, Zhang J, Nansel T, Andrews W, et al. . Association between periodontal disease, bacterial vaginosis, and sexual risk behaviours. J Clin Periodontol. (2010) 37:888–93. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01593.x [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

179. Mindel A, Sawleshwakar S. Physical barrier methods: acceptance, use, and effectiveness. In: Stanberry LR, Rosenthal SL, editors. , editors. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Vaccines, Prevention, and Control. London: Elsevier; (2012). p. 189–212.

180. Weller S, Davis K. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2002) CD003255. 10.1002/14651858.CD003255 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

181. Giannou FK, Tsiara CG, Nikolopoulos GK, Talias M, Benetou V, Kantzanou M, et al. . Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on HIV serodiscordant couples. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. (2016) 16:489–99. 10.1586/14737167.2016.1102635 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

182. Hearst N, Chen S. Condom promotion for AIDS prevention in the developing world: is it working? Stud Fam Plann. (2004) 35:39–47. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2004.00004.x [PubMed] [CrossRef]

183. Munro HL, Pradeep BS, Jayachandran AA, Lowndes CM, Mahapatra B, Ramesh BM, et al. . Prevalence and determinants of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in a general population-based sample in Mysore district, Karnataka state, southern India. AIDS (2008) 22:S117–25. 10.1097/01.aids.0000343770.92949.0b [PubMed] [CrossRef]

184. Lopez LM, Otterness C, Chen M, Steiner M, Gallo MF. Behavioral interventions for improving condom use for dual protection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013) 10:CD010662 10.1002/14651858.CD010662 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

185. Padian NS, van der Straten A, Ramjee G, Chipato T, de Bruyn G, Blanchard K, et al. . Diaphragm and lubricant gel for prevention of HIV acquisition in southern African women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (2007) 370:251–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60950-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

186. Winer RL, Hughes JP, Feng Q, O'Reilly S, Kiviat NB, Holmes KK, et al. . Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med. (2006) 354:2645–54. 10.1056/NEJMoa053284 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

187. Valasoulis G, Koliopoulos G, Founta C, Kyrgiou M, Tsoumpou I, Valari O, et al. . Alterations in human papillomavirus-related biomarkers after treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. (2011) 121:43–8. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.12.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

188. Lam JU, Rebolj M, Dugue PA, Bonde J, von Euler-Chelpin M, Lynge E. Condom use in prevention of human papillomavirus infections and cervical neoplasia: systematic review of longitudinal studies. J Med Screen (2014) 21:38–50. 10.1177/0969141314522454 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

189. Sanchez T, Finlayson T, Drake A, Behel S, Cribbin M, Dinenno E, et al. . Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk, prevention, and testing behaviors–United States, National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System: men who have sex with men, November 2003-April 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. (2006) 55:1–16. [PubMed]

190. Jadack RA, Yuenger J, Ghanem KG, Zenilman J. Polymerase chain reaction detection of Y-chromosome sequences in vaginal fluid of women accessing a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Sex Transm Dis. (2006) 33:22–5. 10.1097/01.olq.0000194600.83825.81 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

191. Donovan B, Ross MW. Preventing HIV: determinants of sexual behaviour (review). Lancet (2000) 355:1897–901. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02302-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

192. Kang M, Rochford A, Johnston V, Jackson J, Freedman E, Brown K, et al. . Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infection among ‘high risk’ young people in New South Wales. Sex Health (2006) 3:253–4. 10.1071/SH06025 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

193. Caballero-Hoyos R, Villasenor-Sierra A. [Socioeconomic strata as a predictor factor for constant condom use among adolescents] (Spanish). Rev Saude Publ. (2001) 35:531–8. [PubMed]

194. Tapia-Aguirre V, Arillo-Santillan E, Allen B, Angeles-Llerenas A, Cruz-Valdez A, Lazcano-Ponce E. Associations among condom use, sexual behavior, and knowledge about HIV/AIDS. A study of 13,293 public school students. Arch Med Res. (2004) 35:334–43. 10.1016/j.arcmed.2004.05.002 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

195. Morris BJ, Bailey RC, Klausner JD, Leibowitz A, Wamai RG, Waskett JH, et al. . Review: a critical evaluation of arguments opposing male circumcision for HIV prevention in developed countries. AIDS Care (2012) 24:1565–75. 10.1080/09540121.2012.661836 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

196. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). World AIDS Day (2018). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6747a1.htm (Accessed December 14, 2018).

197. Mascolini M, Kort R, Gilden D. XVII International AIDS Conference: From Evidence to Action - Clinical and biomedical prevention science. J Int AIDS Soc. (2009) 12:S4. 10.1186/1758-2652-12-S1-S4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

198. Cates W, Feldblum P. HIV prevention research: the ecstasy and the agony. Lancet (2008) 372:1932–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61824-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

199. Gray RH. Methodologies for evaluating HIV prevention intervention (populations and epidemiologic settings). Curr Opin HIV AIDS (2009) 4:274–8. 10.1097/COH.0b013e32832c2553 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

200. Check E. Scientists rethink approach to HIV gels. Nature (2007) 446:12. 10.1038/446012a [PubMed] [CrossRef]

201. Anonymous Trials halted after gel found to increase HIV risk. Nature (2007) 445:577.

202. Anonymous Trial and failure. Nature (2007) 446:1 10.1038/446001a [PubMed] [CrossRef]

203. Anonymous Newer approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet (2007) 369:615 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60285-2 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

204. Ramjee G, Govinden R, Morar NS, Mbewu A. South Africa's experience of the closure of the cellulose sulphate microbicide trial. PLoS Med. (2007) 4:e235. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040235 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

205. Cohen J. Microbicide fails to protect against HIV. Science (2008) 319:1026–7. 10.1126/science.319.5866.1026b [PubMed] [CrossRef]

206. McCormack S, Ramjee G, Kamali A, Rees H, Crook AM, Gafos M, et al. . PRO2000 vaginal gel for prevention of HIV-1 infection (Microbicides Development Programme 301): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Lancet (2010) 376:1329–37. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61086-0 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

207. Garland SM, Kjaer SK, Munoz N, Block SL, Brown DR, DiNubile MJ, et al. . Impact and effectiveness of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: a systematic review of 10 years of real-world experience. Clin Infect Dis. (2016) 63:519–27. 10.1093/cid/ciw354 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

208. Chow EPF, Machalek DA, Tabrizi SN, Danielewski JA, Fehler G, Bradshaw CS, et al. . Quadrivalent vaccine-targeted human papillomavirus genotypes in heterosexual men after the Australian female human papillomavirus vaccination programme: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Inf Dis. (2017) 17:68–77. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30116-5 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

209. Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, McQuillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, et al. . Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA (2007) 297:813–9. 10.1001/jama.297.8.813 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

210. Wheeler CM, Hunt WC, Cuzick J, Langsfeld E, Pearse A, Montoya GD, et al. . A population-based study of human papillomavirus genotype prevalence in the United States: baseline measures prior to mass human papillomavirus vaccination. Int J Cancer (2013) 132:198–207. 10.1002/ijc.27608 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

211. Vanska S, Auranen K, Leino T, Salo H, Nieminen P, Kilpi T, et al. . Impact of vaccination on 14 high-risk HPV type infections: a mathematical modelling approach. PLoS ONE (2013) 8:e72088. 10.1371/journal.pone.0072088 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

212. Matthijsse SM, Naber SK, Hontelez JAC, Bakker R, van Ballegooijen M, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, et al. . The health impact of human papillomavirus vaccination in the situation of primary human papillomavirus screening: a mathematical modeling study. PLoS ONE (2018) 13:e0202924. 10.1371/journal.pone.0202924 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

213. Jit M, Vyse A, Borrow R, Pebody R, Soldan K, Miller E. Prevalence of human papillomavirus antibodies in young female subjects in England. Br J Cancer (2007) 97:989–91. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603955 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

214. Stone KM, Karem KL, Sternberg MR, McQuillan GM, Poon AD, Unger ER, et al. . Seroprevalence of human papillomavirus type 16 infection in the United States. J Infect Dis. (2002) 186:1396–402. 10.1086/344354 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

215. Morris BJ, Rose BR. Cervical screening in the 21st century: the case for human papillomavirus testing of self-collected specimens. Clin Chem Lab Med. (2007) 45:577–91. 10.1515/CCLM.2007.127 [PubMed] [CrossRef]

216. Tota JE, Ramanakumar AV, Jiang M, Dillner J, Walter SD, Kaufman JS, et al. . Epidemiologic approaches to evaluating the potential for human papillomavirus type replacement postvaccination. Am J Epidemiol. (2013) 178:625–34. 10.1093/aje/kwt018 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef]